Politics & International Relations

Tinker v. Des Moines

Tinker v. Des Moines was a landmark US Supreme Court case in 1969 that upheld the First Amendment rights of students in public schools. The case involved students who were suspended for wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. The Court ruled that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate."

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

Related key terms

1 of 4

Related key terms

1 of 3

9 Key excerpts on "Tinker v. Des Moines"

- eBook - ePub

Defending the First

Commentary on First Amendment Issues and Cases

- Joseph Russomanno(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

and gave the rest of us the opportunity to learn from the ruling. In the pages that immediately follow, Dan Johnston opens a new door to this fascinating case.***The U.S. Supreme Court case of Tinker vs. Des Moines Independent Community School District,1 decided in 1969, is often called a “landmark” freedom- of-speech case, implying that it was “new” law. But when one examines U.S. Supreme Court decisions prior to Tinker that apply U.S. constitutional principles to public school authorities’ duties and students’ rights, it is hard to see any new legal principles in Tinker.The central issue in Tinker—whether public school officials can restrain an exercise of free expression by students in school, absent some evidence of disruption as a result of the expression—had long before Tinker been settled law in the United States in favor of students. Tinker is an example of a recurring conflict in American politics and law between a majority urge to enforce patriotism and loyalty, and a resistance to those urges when they impose requirements contrary to individual religious or political beliefs. As with Tinker most of these conflicts occur during times of war. As with Tinker, in most of these conflicts, the majority, including judges and other public officials, find it difficult to adhere to our Constitution and laws.THE PRECEDENTS

The pertinent U.S. Supreme Court precedents of Tinker begin with Minersville District v. Gobitis 2 Children who were Jehovah’s Witnesses refused a mandate from the state legislature and their public school to pledge allegiance to, and salute, the U.S. flag. They were suspended from school and their father argued that he and his children were denied their right to public education. Lower federal courts ruled for the children.3 There could be no doubt that constitutional protections of freedom of speech applied to public school authorities. During World War I, the Supreme Court had overturned prohibitions against the teaching of German language in public schools.4 - eBook - ePub

First Amendment Rights

An Encyclopedia [2 volumes]

- Nancy S. Lind, Erik T. Rankin(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- ABC-CLIO(Publisher)

I. Case Background

A. The Supreme Court Cases

The Supreme Court has addressed restrictions on student speech in four cases. The Court’s initial foray into the area, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District ,10 demonstrated a strong commitment to the First Amendment rights of students. Since that time, the Court has shown increasing deference to the choices made by school administrators.11In Tinker , plaintiffs sued for damages and an injunction after school officials disciplined them for wearing black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War.12 The Supreme Court reversed and remanded the district court’s dismissal of the complaint.13 The tone of the opinion was set by the Court’s oft-quoted language that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”14 However, the Court recognized that school discipline involved a balance of interests by acknowledging the “authority of the States and of school officials, consistent with fundamental constitutional safeguards, to prescribe and control conduct in the schools.”15 The Court found the balance favored free speech in Tinker because the disciplined conduct in that case was closely “akin to ‘pure speech’ ” and there was no evidence that the restricted behavior materially disrupted the work of the school or any class or collided “with the rights of other students to be secure and to be let alone.”16 The Court also found it significant that school authorities did not prohibit the wearing of all controversial symbols, but rather, singled out the expression of one particular opinion.17Although the district court concluded that school officials had a reasonable fear of a disturbance, the Court emphasized that an “undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance” or “a mere desire to avoid the discomfort and unpleasantness that always accompany an unpopular viewpoint” could not justify restrictions of otherwise protected student speech.18 The Court held that student speech is protected unless it “materially and substantially interfer[es] with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” or “collid[es] with the rights of others.”19 - eBook - ePub

- Randall Curren(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

The legal treatment of free speech in schools varies across countries: in the United States, the contemporary history of how the courts have dealt with speech in education, particularly in K-12 education, provides an example of how “mission” can imply boundaries. As noted above, the Tinker test set by the Court decided that speech which would “materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” could be prohibited. The school's mission is to educate its students, and thus, interfering with that mission by sufficiently disrupting the conditions in which that education occurred established the “learning environment” boundary. In Tinker, speech won the day, but since then, the courts have continuously restricted students' speech rights by expanding the scope of what is required for a suitable learning environment. In that, the Courts have generally not taken minors to be citizens deserving of full constitutional protections, and whose views deserve to be heard. The Court in the decades since Tinker has restricted a student's right to engage in an innuendo laden political campaign speech for a classmate (Bethel School District v. Fraser, 1986); students’ rights to cover controversial topics such as teen pregnancy and divorce in their school newspaper (Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 1988); and nonsensical student pranks, such as a student unfurling a banner at an out-of-school event reading “BONG HiTS 4 JESUS” (Morse v. Frederick 2007). The most recent decision at the time of drafting this chapter, however, represented a departure from this trend. In 2021, the Court upheld a student's right to use profanity on social media outside of school in expressing her frustration with her club sport placement (Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.) - eBook - ePub

- Michael Imber, Tyll van Geel, J.C. Blokhuis, Jonathan Feldman(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

In 1992, the Ninth Circuit considered a case in which students claimed a violation of their free speech rights when school officials required them to remove buttons critical of replacement teachers hired during a strike of regular teachers. School officials claimed the buttons were disruptive, but a replacement teacher confirmed that there had been no disruption in her class. In deciding the case, the court declined to rely on Fraser because the buttons, which bore such slogans as “I’m not listening to scabs” and “Do scabs bleed?” were not lewd, vulgar, or plainly offensive. Hazelwood did not apply either, said the court, because this was not the kind of speech that the public was likely to believe carried the imprimatur of the school. Thus, basing its ruling solely on Tinker, the court ruled in favor of the students because school officials had been unable to prove that the buttons were disruptive: “The passive expression of a viewpoint in the form of a button worn on one’s clothing is certainly not in the class of those activities which inherently distract students and break down the regimentation of the classroom.” 71 4.4 Independent Student Speech The first Supreme Court case to consider the issue of student free speech rights was Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District. 72 As the cases considered in the previous two sections repeatedly affirm, Tinker is still the precedent that controls the regulation of student speech that does not fall into one of the unprotected categories of speech examined in Section 4.2, and is not school-sponsored as discussed in Section 4.3. Tinker controls the regulation of what the Court referred to as “independent student speech.” The Tinker Case Tinker involved a group of students who decided along with their parents to wear black armbands to indicate their objections to the Vietnam War - eBook - ePub

- Catherine J. Ross(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

Ginsberg , parents can override the state’s judgment about what is good for their children and decide when their children are ready to handle sexual materials that may be titillating but do not meet the legal definition of obscenity for adults. Moreover, in contrast to unprotected obscene speech, where the Constitution requires only that governmental restraint be rational, the Tinkers’ speech was political and fell squarely within the First Amendment’s protected sphere.On the most important aspects of Tinker , however, Justice Stewart agreed with the majority: that speakers were young or were students did not diminish their First Amendment protections; and because the First Amendment applied to the black armbands, a standard more demanding than mere reasonableness was required to suppress them.“Reasonable” rules, the Court rebuked the Des Moines school district, are not sufficient to overcome the constitutional presumption against silencing speech. “[I]n our system,” the Court explained, “undifferentiated fear or apprehension of disturbance is not enough to overcome the right to freedom of expression. Any departure from absolute regimentation may cause trouble. Any variation from the majority’s opinion may inspire fear. Any word spoken, in class, in the lunchroom, or on the campus, that deviates from the views of another person may start an argument or cause a disturbance.” “But,” the Court stated starkly, “our Constitution says we must take this risk.”50The majority opinion made clear that the Des Moines schools had crossed other bright lines in their treatment of the armbands. Administrators had silenced the protesters based on the content of the message they intended to communicate. Officials hadn’t treated all symbolic speech in the same way but chose favored and disfavored viewpoints: The schools ignored buttons about national political campaigns and even the “Iron Cross, traditionally a symbol of Nazism,” that some students wore before and after the antiwar protest. School authorities singled out for condemnation a particular student viewpoint: speech opposing the war. Far from being “reasonable,” the schools’ rule violated two basic premises of the Speech Clause by engaging in both content and viewpoint discrimination, and the after-the-fact rationale that other students might respond badly smacked of allowing hecklers to veto unpopular speech.51 - eBook - ePub

Academic Freedom

Autonomy, Challenges and Conformation

- Robert J. Ceglie, Sherwood Thompson, Robert J. Ceglie, Sherwood Thompson, Robert Ceglie, Sherwood Thompson(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Emerald Publishing Limited(Publisher)

Sadler & Oats, 2013 , p. 365). The decision went on to explain that this student speech, even when controversial, can proceed as long as it does so without interference to the operation of school functions or interruption to the rights of others. In applying this ruling to the daily life of educators, students, and schools, the ruling differentiates clearly what is and is not acceptable. Teacher and student speech that is simply uncomfortable is protected speech, but that which interrupts the learning of others or the function of a school as a learning environment, is not appropriate and is not protected.Yet, even with this clarity, Tinker , like many of these cases, includes ambiguity when compared to reality in schools. In the most difficult or controversial of school situations and in applying the principles of Tinker , one must ask two key questions:1) At what point did the situation substantially disrupt the learning environment?2) Who, exactly, is causing the disruption? The student? Or those in opposition to the student’s views? (Sadler & Oats, 2013 )As part of the Tinker ruling, Justice Fortas also added:In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as out of school are “persons” under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate. (Alexander & Alexander, 1985 , p. 329)Elrod v. Burns ( 1976)This case is key to the examination of academic freedom and free speech as it determined the relevance of rank or position in the determination of protections. In 1970, Cook County Sheriff Richard Burns fired several employees who were of a different political party than his own. The employees involved included a chief deputy, a bailiff, and a process server. In its 1976 decision, the US Supreme Court that employer political patronage infringes on the employees’ own political beliefs, which are protected by the First Amendment (Hudson, 2002 - eBook - ePub

Neoconservative Politics and the Supreme Court

Law, Power, and Democracy

- Stephen M. Feldman(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

Most likely, Thomas and Scalia would have signed on to Roberts’s opinion even if it had been more unequivocally republican democratic, yet Alito and Kennedy might have resisted. Kennedy joined not only Roberts’s majority opinion but also Alito’s concurrence, following a pluralist democratic approach. And for Roberts and Alito (as well as Kennedy), the precedential weight of Tinker apparently played a strong role. Despite Bethel and Hazelwood, Tinker remains the seminal case in this area, so any dispute raising issues involving students’ free-expression rights will come within its gravitational pull. Just as one could not possibly write an opinion resolving an abortion dispute without accounting for Roe v. Wade, one cannot disregard Tinker. And as much as any free-expression case, Tinker accepts the pluralist democratic substantiation of free expression as a constitutional lodestar. Free Expression and Religion Free-speech issues have arisen repeatedly when private (nongovernmental) actors have sought to express certain religious views or values on government-owned property. Widmar v. Vincent, decided in 1981, was the first case to raise such an issue squarely. A state university opened its facilities for meetings held by registered student organizations but refused to allow its buildings and grounds to be used “for purposes of religious worship or religious teaching.” In this particular instance, the university refused access to Cornerstone, a student “organization of evangelical Christian students from various denominational backgrounds.” Cornerstone members challenged the university policy by arguing that it violated both their free-expression and free-exercise rights. The university, meanwhile, maintained that allowing religious organizations to use its facilities would violate the Establishment Clause. This swirl of free-expression and religious freedom claims generated an odd political alignment of justices - eBook - ePub

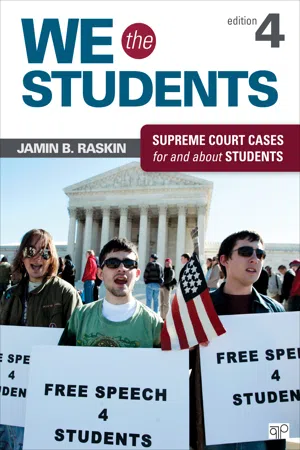

We the Students

Supreme Court Cases for and about Students

- Jamin B. Raskin(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CQ Press(Publisher)

Language used to other scholars to stir up disorder and subordination, or to heap odium and disgrace upon the master; writings and pictures placed so as to suggest evil and corrupt language, images and thoughts to the youth who must frequent the school; all such or similar acts tend directly to impair the usefulness of the school, the welfare of the scholars and the authority of the master. By common consent and by the universal custom in our New England schools, the master has always been deemed to have the right to punish such offences. Such power is essential to the preservation of order, decency, decorum and good government in schools.Justice Thomas assailed the Tinker decision, saying that it created a rule not rooted in the First Amendment that is now riddled with exceptions. He wrote:He concluded:Today, the Court creates another exception. In doing so, we continue to distance ourselves from Tinker, but we neither overrule it nor offer an explanation of when it operates and when it does not. I am afraid that our jurisprudence now says that students have a right to speak in schools except when they don't—a standard continuously developed through litigation against local schools and their administrators. In my view, petitioners could prevail for a much simpler reason: As originally understood, the Constitution does not afford students a right to free speech in public schools.I join the Court's opinion because it erodes Tinker's hold in the realm of student speech, even though it does so by adding to the patchwork of exceptions to the Tinker standard. I think the better approach is to dispense with Tinker altogether, and given the opportunity, I would do so.Dissenting Voices

Justice Stevens was joined by Justice Souter and Justice Ginsburg in his dissenting opinion. He wrote:In my judgment, the First Amendment protects student speech if the message itself neither violates a permissible rule nor expressly advocates conduct that is illegal and harmful to students. This nonsense banner does neither, and the Court does serious violence to the First Amendment in upholding—indeed, lauding—a school's decision to punish Frederick for expressing a view with which it disagreed.Justice Stevens said that the Court's test about advocating use of illegal drugs invites stark viewpoint discrimination. In this case, for example, the principal has unabashedly acknowledged that she disciplined Frederick because she disagreed with the pro-drug viewpoint she ascribed to the message on the banner…. [T]he Court's holding in this case strikes at ‘the heart of the First Amendment’ because it upholds a punishment meted out on the basis of a listener's disagreement with her understanding (or, more likely, misunderstanding) of the speaker's viewpoint. - eBook - ePub

Deciding Communication Law

Key Cases in Context

- Susan Dente Ross(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

supra, at 602, the principal used a paper shredder. He objected to some material in two articles, but excised six entire articles. He did not so much as inquire into obvious alternatives, such as precise deletions or additions (one of which had already been made), rearranging the layout, or delaying publication. Such unthinking contempt for individual rights is intolerable from any state official. It is particularly insidious from one to whom the public entrusts the task of inculcating in its youth an appreciation for the cherished democratic liberties that our Constitution guarantees.IV. The Court opens its analysis in this case by purporting to reaffirm Tinker’s time-tested proposition that public school students “do not ‘shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.’” Ante, at 266 (quoting Tinker, supra, at 506). That is an ironic introduction to an opinion that denudes high school students of much of the First Amendment protection that Tinker itself prescribed. Instead of “teach[ing] children to respect the diversity of ideas that is fundamental to the American system,” Board of Education v. Pico, 457 U.S., at 880 (BLACKMUN, J., concurring in part and concurring in judgment), and “that our Constitution is a living reality, not parchment preserved under glass,” Shanley v. Northeast Independent School Dist., Bex ar Cty Tex., 462 F. 2d 960, 972 (CA5 [291] 1972), the Court today “teach[es] youth to discount important principles of our government as mere platitudes.” West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S., at 637. The young men and women of Hazelwood East expected a civics lesson, but not the one the Court teaches them today.I dissent.Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System v. Southworth

529 US. 217 (2000) (Excerpts only. Footnotes omitted.)

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

Explore more topic indexes

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 6

Explore more topic indexes

1 of 4