![]()

1

The modern management of cancer: an introductory note

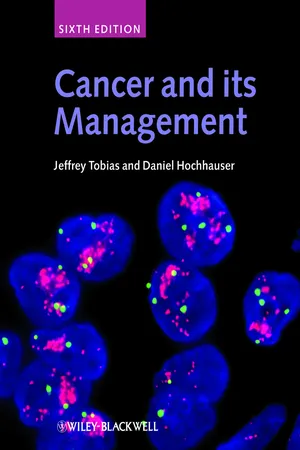

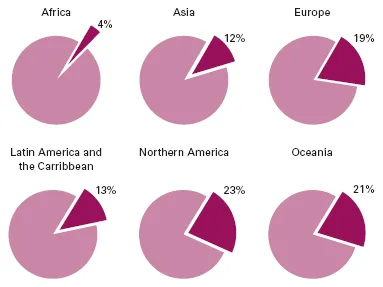

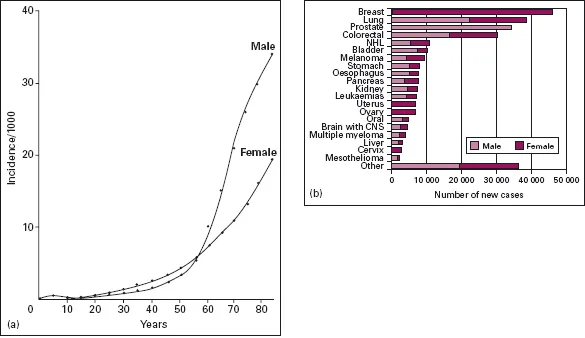

Cancer is a vast medical problem. It is now the major cause of mortality, both in the UK and elsewhere in the Western world [1] (Figure 1.1), diagnosed each year in one in every 250 men and one in every 300 women. The incidence rises steeply with age so that, over the age of 60, three in every 100 men develop the disease each year (Figure 1.2a). It is a costly disease to diagnose and investigate, and treatment is time-consuming, labourintensive and usually requires hospital care. In the Western world the commonest cancers are of the lung, breast, skin, gut and prostate gland [2,3] (Figures 1.2b and 1.3). The lifetime risk of developing a cancer is likely to alter sharply over the next decade because the number of cancer cases has risen by nearly one-third over the past 30 years. An ageing population, successes from screening and earlier diagnosis have all contributed to the rise. Present estimates suggest that the number of cases is still rising at a rate of almost 1.5% per annum. The percentage of the population over the age of 65 will grow from 16% in 2004 to 23% by 2030, further increasing the overall incidence [4].

For many years the main methods of treating cancer were surgery and radiotherapy. Control of the primary tumour is indeed a concern, since this is usually responsible for the patient’s symptoms. There may be unpleasant symptoms due to local spread, and failure to control the disease locally means certain death. For many tumours, breast cancer for example, the energies of those treating the disease have been directed towards defining the optimum methods of eradication of the primary tumour. It is perhaps not surprising that these efforts, while improving management, have not greatly improved the prognosis because the most important cause of mortality is metastatic spread. Although prompt and effective treatment of the primary cancer diminishes the likelihood of recurrence, metastases have often developed before diagnosis and treatment have begun. The prognosis is not then altered by treatment of the primary cancer, even though the presenting symptoms may be alleviated. Progress in treatment has been slow but steady. Worldwide, between 1990 and 2001, the mortality rates from all cancers fell by 17% in patients aged 30–69 years, but rose by 0.4% in those aged 70 years or older [1,5]. This may sound impressive at first reading, but the fall was lower than the decline in mortality rates from cardiovascular disease, which decreased by 9% in the 30–69 year age group (men) and by 14% in the 70 year (or older) age group. In the UK there has been a steady fall in mortality from cancer of about 1% a year since the 1990s (Figure 1.4), but with a widening gap in the differing socioeconomic groups. As the authors forcefully state [2]: ‘Increases in cancer survival in England and Wales during the 1990s are shown to be significantly associated with a widening deprivation gap in survival.’ In the USA, the number of cancer deaths has now fallen over the past 5 years, chiefly due to a decline in deaths from colorectal cancer, itself thought to be largely due to an increase in screening programmes. Interestingly, the fall in mortality has also been paralleled by a reduction in incidence rates in the USA – for men since 1990 and for women since 1991 [6]. Nonetheless, cancer continues as the leading cause of death in the USA, under the age of 85 years [3].

Every medical specialty has its own types of cancer which are the concern of the specialist in that area. Cancer is a diagnosis to which all clinicians are alerted whatever their field and, because malignant disease is common, specialists acquire great expertise in diagnosis, often with the aid of techniques such as bronchoscopy and other forms of endoscopy. Conversely, the management of cancer once the diagnosis has been made, especially the non-surgical management, is not part of the training or interest of many specialists. This has meant that radiotherapists (‘clinical oncologists’) and medical oncologists are often asked to see patients who have had a laparotomy at which a tumour such as an ovarian cancer or a lymphoma has been found, but the abdomen then closed without the surgeon having made an attempt to stage the disease properly or, where appropriate, to remove the main mass of tumour. This poses considerable problems for the further management of the patient. More generally, lack of familiarity with the principles of cancer management, and of what treatment can achieve, may lead to inappropriate advice about outcome and a low level of recruitment into clinical trials. An understanding of the principles of investigation and treatment of cancer has become essential for every physician and surgeon if the best results for their patients are to be achieved.

Figure 1.1 Percentage of all deaths due to cancer in the different regions of the world. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/geographic/world/mortality/?a=5441, accessed 10 September 2008.(© Cancer Research UK.)

Figure 1.2 (a) Age-specific cancer incidence in England and Wales. (b) The 20 most commonly diagnosed cancers (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) in the UK, 2005. NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/commoncancers/, accessed 10 September 2008. (© Cancer Research UK.)

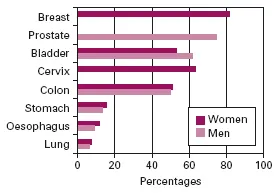

Figure 1.3 (a) The 10 most common cancers in males (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) in the UK, 2005. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/males/, accessed 10 September 2008. (b) The 10 most common cancers in females (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer) in the UK, 2005. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/incidence/females/?a=5441, accessed 10 September 2008. NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. (© Cancer Research UK.)

Figure 1.4 Cancer survival rates improved between 1999 and 2004. Available at http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=861. (Reproduced under the terms of the Click-Use Licence.)

During the latter part of the last century, advances in the chemotherapy and radiotherapy of uncommon tumours such as Hodgkin’s disease and germ-cell tumours of the testis, together with the increasing complexity of treatment decisions in more common tumours, led to a greater awareness of the importance of a planned approach to clinical management. This applies not only for the problems in individual patients, but also in the planning of clinical trials. For each type of cancer, an understanding of which patients can be helped, or even cured, can only come by close attention to the details of disease stage and pathology. Patients in whom these details are unknown are at risk from inappropriate over-treatment or from inadequate treatment, resulting in the chance of cure being missed. Even though chemotherapy has not on the whole been of outstanding benefit to patients with diseases such as squamous lung cancer or adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, it is clearly essential that clinicians with a specialized knowledge of the risks and possible benefits of chemotherapy in these and other diseases are part of the staff of every oncology department. Knowing when not to treat is as important as knowing when to do so.

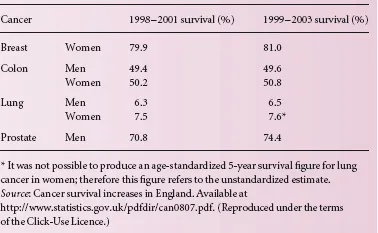

For many cancers, improvements in chemotherapy have greatly increased the complexity of management. Cancer specialists have a particular responsibility to validate the treatments they give, since the toxicity and dangers of many treatment regimens mean that the clinical indications have to be established precisely. In a few cases an imaginative step forward has dramatically improved results and the need for controlled comparison with previous treatment is scarcely necessary. Examples are the early studies leading to the introduction of combination chemotherapy in the management of advanced Hodgkin’s disease, and the prevention of central nervous system relapse of leukaemia by prophylactic treatment. However, such clear-cut advances are seldom made (see, for example, Table 1.1, which outlines the modest improvement in survival for four major types of cancer between 1998 and 2003 in England). For the most part, improvements in treatment are made slowly in a piecemeal fashion and prospective trials of treatment must be undertaken in order to validate each step in management. Modest advances are numerically nonetheless important for such common diseases. Only large-scale trials can detect these small differences reliably. Collaboration on a national and international scale has become increasingly important, and the results of these studies have had a major impact on management, for example in operable breast cancer. There is always a tendency in dealing with cancer to want to believe good news and for early, uncontrolled, but promising results to be seized upon and over-interpreted. Although understandable, uncritical enthusiasm for a particular form of treatment is greatly to be deplored, since it leads to a clamour for the treatment and the establishment of patterns of treatment that are improperly validated. There have been many instances where treatments have been used before their place has been clearly established: adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer, limb perfusion in sarcomas and melanoma, radical surgical techniques for gastric cancer and adjuvant chemotherapy for bladder cancer are examples. The toxicity of cancer treatments is considerable and can only be justified if it is unequivocally shown that the end-results are worthwhile either by increasing survival or by improving the quality of life.

Table 1.1 The 5-year relative survival for adults diagnosed with major cancers during 1998–2001 and 1999–2003, England.

The increasing complexity of management has brought with it a recognition that in most areas it has become necessary to establish an effective working collaboration between specialists. Joint planning of management in specialized clinics is now widely practised for diseases such as lymphomas and head and neck and gynaecological cancer. Surgeons and gynaecologists are now being trained who specialize in the oncological aspects of their specialty. In this way patients can benefit from a coordinated and planned approach to their individual problems.

Before a patient can be treated, it must be established that he or she has cancer, the tumour pathology must be defined, and the extent of local and systemic disease determined. For each of these goals to be attained the oncologist must rely on colleagues in departments of histopathology, diagnostic imaging, haematology and chemical pathology. Patients are often referred in whom the diagnosis of cancer has not been definitely made pathologically but is based on a very strong clinical suspicion with suggestive pathological evidence, or where a pathological diagnosis of cancer has been made which, on review, proves to be incorrect. It is essential for the oncologist to be in close contact with histopathologists and cytologists so that diagnoses can be reviewed regularly. Many departments of oncology have regular pathology review meetings so that the clinician can learn of the difficulties which pathologists have with diagnosis and vice versa. Similarly, modern imaging techniques have led to a previously unattainable accuracy in preoperative and postoperative staging, although many of these techniques are only as reliable as the individuals using them (e.g. abdominal or pelvic ultrasound). The cancer specialist must be fully conversant with the uses and limitations of imaging methods. The techniques are expensive and the results must be interpreted in the light of other clinical information. The practice of holding regular meetings to review cases with specialists from the imaging departments has much to commend it.

Modern cancer treatment often carries a substantial risk of toxicity. Complex and difficult treatments are best managed in a specialized unit with skilled personnel. The centralization of high-dependency care allows staff to become particularly aware of the physical and emotional problems of patients undergoing treatments of this kind. Additionally, colleagues from other departments such as haematology, biochemistry and bacteriology can more easily help in the investigation and management of some of the very difficult problems which occur, for example in the immunosuppressed patient.

The increasingly intensive investigative and treatment policies which have been adopted in the last 25 years impose on clinicians the additional responsibility of having to stand back from the treatment of their patients and decide on the aim of treatment at each stage. Radical and aggressive therapy may be essential if the patient is to have a reasonable chance of being cured. However, palliative treatment will be used if the situation is clearly beyond any prospect of cure. It is often difficult to decide when the intention of treatment should move from the radical to the palliative, with avoidance of toxicity as a major priority. For example, while many patients with advanced lymphomas will be cured by intensive combination chemotherapy, there is no prospect of cure in advanced breast cancer by these means, and chemotherapy must in this case be regarded as palliative therapy. In this situation it makes little sense to press treatment to the point of serious toxicity. The judgement of what is tolerable and acceptable is a major task in cancer management. Such judgements can only come from considerable experience of the treatments in question, of the natural history of individual tumours and an understanding of the patient’s needs and wishes.

Modern cancer management often involves highly technological and intensive medical care. It is expensive, time-consuming and sometimes dangerous. Patients should seldom be in ignorance of what is wrong with them or what the treatment involves. The increasingly technical nature of cancer management, and the change in public and professional attitudes towards malignant disease, have altered the way in which doctors who are experienced in cancer treatment approach their patients. There has been a decisive swing towards honest and careful discussion with patients about the disease and its treatment. This does not mean that a bald statement should be made to the patient about the diagnosis and its outcome, since doctors must sustain the patient with hope and encouragement through what is obviously a frightening and depressing period. Still less does it imply that the decisions about treatment are in some way left to the patient after the alternatives have been presented. Skilled and experienced oncologists advise and guide patients in their understanding of the disease and the necessary treatment decisions. One of the most difficult and rewarding aspects of the management of malignant disease lies in the judgement of how much information to give each particular patient, at what speed, and how to incorporate the patient’s own wishes into a rational treatment plan.

The emotional impact of the diagnosis and treatment can be considerable for both patients and relatives. Above everything else, treating patients with cancer involves an awareness of how patients think and feel. All members of the medical team caring for cancer patients must be prepared to devote time to talking to patients and their families, to answer questions and explain what is happening and what can be achieved. Because many patients will die from their disease, they must learn to cope with the emotional and physical needs of dying patients and the effects of anxiety, grief and bereavement on their families.

In modern cancer units management is by a team of healthcare professionals, each of whom has their own contribution to make. They must work together, participating in management as colleagues commanding mutual respect. The care and support of patients with advanced malignant disease and the control of symptoms such as pain and nausea have greatly improved in the last 10 years. This aspect of cancer management has been improved by the collaboration of many medical workers. Nurses who specialize in the control of symptoms of malignancy are now attached to most cancer units, and social workers skilled in dealing with the problems of malignant disease and bereavement are an essential part of the team. The development of hospices has led to a much greater appreciation of the way in which symptoms might be controlled and to a considerable improvement in the standard of care of the dying in general hospitals. Many cancer departments now have a symptom support team based in the hospital but who are able to undertake the care of patients in their own homes, giving advice on control of symptoms such as pain and nausea and providing support to patients’ families.

There have been dramatic advances in cell and molecular biology in the last 20 years, with the result that our understanding of the nature of malignant transformation has rapidly increased. This trend will continue, placing many additional demands on oncologists to keep abreast of both advances in management and the scientific foundations on which they are based. The power of modern techniques to explore some of the fundamental processes in malignant transformation has meant that cancer is at the heart of many aspects of medical research, and has led to an increased academic interest in malignancy. This, in turn, has led to a more critical approach to many aspects of cancer treatment. Cancer, and its management, is unquestionably among the most complex and demanding disciplines within medicine, and many more healthcare workers now recognize that cancer medicine is a profoundly rewarding challenge. Standards of patient care have improved dramatically as a result of these welcome changes.

References

1 Danaei G, Vander Hoorn S, Lopez AD et al. Causes of cancer in the world: comparative risk assessment of nine behavioural and environmental risk factors. Lancet 2005; 366: 1784–93.

2 Coleman MP, Rachet B, Woods LM et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in cancer survival in England and Wales up to 2001. Br J Cancer 2004; 90: 1367–73.

3 Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani...