![]()

Chapter 1

Commentary Flows

A largely unspoken expectation in biblical scholarship is for a Bible commentary to locate and explain a biblical book in accordance with the assumed intentions of the author(s) and the sociopolitical world(s) in which the book was written (see Ben Zvi 2003; Handy 2007), noting how the purposes for and meanings of the book may have changed or taken new shapes when that book was edited, redacted, canonized, translated and interpreted in religious and secular settings (see Limburg 1993: 99–123; Jenson 2008; Caspi and Greene 2011; Bob 2013). It is thus expected that the author(s) of a Bible commentary dive into and through the rhetoric of the book to explain how its parts relate to each other, to resolve textual problems, to reconcile translation variances, to determine the histories behind and in the book, and to survey the scholarly literature on that book. On those matters, a mainline Bible commentary is expected to offer a set of critical notes and reasonable explanations that determine original meanings and assert correct interpretations.1

With respect to the book of Jonah, despite its brevity, the array of commentaries and scholarly literature is voluminous and varied. The reception history of the book is dense and heavy extending from the shadows of Eden (see Berger 2016) onto the canvases of artists, the winks of satirists (see McKenzie 2005: 1–21), the directions of ethicists (see De La Torre 2007), the shelves of adult and children literature as well as to toys, computer games and the big screen (see Sherwood 2000). At different times, new and novel approaches to biblical criticism have been trialled with Jonah,2 but not all creative and critical approaches find the book of Jonah appealing or relevant. This broad range has a lot to say about readers as well (see Lasine 2016; on implied and actual readers of Jonah, see Person Jr. 1996: 90–163). What new insights then could an Earth Bible Commentary (EBC) add to the study of Jonah?3 And why should i,4 whose first response is usually to flee from the business of Bible commentaries, write this EBC volume?

My response to the second question is simple, following Norman Habel’s lead, because the EBC series “requires a radical re-orientation to the biblical text” (Habel 2011: 3). I did not flee from this assignment because, appropriating images from the Jonah narrative, it is an opportunity for me to throw the commentary genre into the stormy seas of reading.5 Time will tell what impact this attempt might have and if the minders (or gods) of the commentary business will send a huge fish to rescue the commentary genre, but this EBC volume seeks to embrace the opportunities that wait from the hinterland of Nineveh. My orientation towards and beyond Nineveh is not because that was the place where God wanted Jonah to go, or because Nineveh was a godforsaken place (see Lindsay 2016). Rather, i am interested in Nineveh because there were beasts there that had something to teach God (and this becomes clear only at the end of the narrative, Jon. 4.10-11) and readers about life and rescue. It is for this reason that in this commentary, in the company of David Clines (1995, 1998) and David Jobling (1998), i read Jonah forward (in the direction of the Hebrew text, right to left) in Chapters 2–3, and then backward (left to right) in Chapters 4–9. Ideologically, this EBC volume flows both ways.

Reading Jonah in both directions problematizes the traditional textual parameters and linear readerly orientations that mainline critics place upon the narrative. One of the inspirations for this bi-textual flow is David Jobling’s commentary on 1 Samuel. Jobling subverts the way that “the canonical division exerts tremendous pressure on scholars to read the beginning of 1 Samuel as a new beginning—to read it forward [into 2 Samuel] rather than backward [from Judges]” (Jobling 1998: 33; emphasis in original). Concluding that the literary patterns of the book of Judges continue into 1 Samuel, and refusing to be tripped by the interruption that the book of Ruth (which points readers to David) inserts in the Christian Old Testament canons, Jobling’s commentary on 1 Samuel starts (back) in the book of Judges. Jobling reads 1 Samuel backward, taking 1 Samuel as part of the “Extended Book of Judges,” as well as forward (see also West 2019).

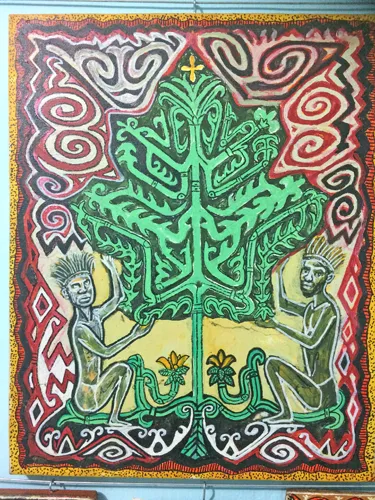

The other inspiration for the forward-and-backward orientation of this commentary comes from the subversive indigenous wisdom of the late West Papuan artist Donatus S. Moulo Moiwend (aka Donet), who counts among the normal people (see Preface). Of critical relevance for this commentary is Donet’s “roots and leaves” works, which subvert conventional thinking concerning the parts of a tree as metaphors for human generations. Conventional thinking takes the roots of a tree to represent the ancestors, the trunk to represent the parents and the branches to represent the current generation. The fruits and leaves, which are younger, delicate and in need of gentle care, represent the children. This logic is reflected in one of the teachings of Jesus: “I am the vine, you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing” (John 15.5, NRSV). Jesus represented the conventional thinking that the branches (current generation) cannot exist without the vine or tree-trunk (parents, teachers) and the roots (ancestors), and this complementary relation is necessary in order for the vine to bear fruits (read: next generation). Donet, giving expression to traditional Papuan wisdom, overturned this way of thinking in his body of works around roots and leaves.

For Donet, the leaves represent the ancestors because leaves give air for breathing and sap for healing (see Figure 1.1, on which Donet painted a face to represent the ancestors on a dried palm leaf). The leaves (ancestors) give the current generation life, sustenance and healing. The days of the ancestors have expired, but they are not absent from the world of the living. The ancestors continue to be present in the healing powers of (green) leaves, in the whispering and singing of leaves in the wind, and in the rattling of dry (brown) leaves when the wind blows them around or when living creatures step on them. According to Donet’s way of thinking, the world of the ancestors is not separate from this world of the current generation. Rather, the people of the current time live in the world of the ancestors (compare to assumptions in traditional theology about world or city of God). This way of thinking may be unconventional to foreign minds, but it is deeply rooted and very traditional in Donet’s Papua—the largest island in Pasifika (for the region of Pacific Islands, South Sea Islands, Oceania).6

Figure 1.1 Donatus S. Moulo Moiwend, Guardian of the Palm Leaves (oil on palm leaf, 2010). Used with permission of the Moiwend family.

The trunk (body) and the branches represent the current generation. They provide the base and veins for and from the leaves (ancestors), while the roots represent the children (future generation) because it is out of the roots that shoots (new life) spring. In Figure 1.2, the roots are also green to indicate that new life starts from the roots. Roots represent new beginnings and the life that wait in the future (read: next generation). Life comes out and up from the roots. Even when a new plant springs from dried seeds, the roots unfold first before the shoot rises.

Figure 1.2 Donatus S. Moulo Moiwend, Tree of Life (oil on bark, undated).7 Used with permission of the Moiwend family.

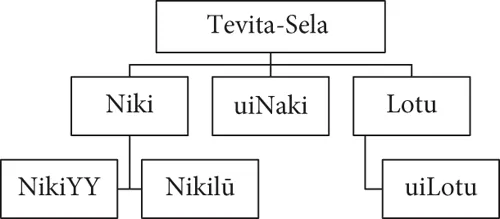

Donet’s thinking has support from two traditional corners: First, from an ancient literary culture, the “stump of Jesse” metaphor in the Bible proposes that “a branch from its roots will bear fruit” (Isa. 11.1). The tree is dead—a stump is what remains—but life is in the roots. And second, from ancient oral cultures, the mapping of whakapapa (Māori for genealogy) is commonly identified as “family tree” and because of the top-to-bottom reading orientation of most cultures the roots are taken to be the children and grandchildren (see Figure 1.3). The family tree grows down, and the future of life is underneath.

Figure 1.3 Family tree.

In honour of Donet, i turn the Jonah narrative over looking for roots at the end of the book, and so, following Jobling’s lead, i read the narrative forward as well as backward. In reading Jonah both ways, the significance of the beasts and of the city of Nineveh (both of whom caught the focus in the final scene, Jon. 4.10-11) is taken seriously in this commentary. In reading backward (from the end to the beginning), one reads from the dusty, sandy and rocky hinterland of Nineveh, which invites one to return (to) the narrative with sand and pebbles in one’s eyes and toes (a mark of islander criticism, see Davidson 2015).

The experience of paying attention to the agency of beasts while reading a narrative backward is similar to the experience of being sucked into the moana (deep sea) by a rip (see Havea 2007). A rip is like a washing machine: it spins and then wrings, and it may even bruise, its victim (in this context, the reader). One (i.e. a reader) cannot control a rip (a text), and one will drown if she or he fights back. One has a better chance of surviving by simply relaxing and allowing the rip to take her or him into the deep, then swim around the rip onto shore. Returning from the experience of drifting in a rip, familiar to islanders, to the task of commenting on a biblical text, this EBC volume goes against the will of commentators who seek to determine and control texts and their meanings.

I did not flee from (but i did delay completing) this assignment, also, because i am not fully on board with the EBC agenda. There are aspects that i appreciate, like the six ecojustice principles—intrinsic worth, interconnectedness, voice, purpose, mutual custodianship, resistance (see Habel 2011: 1–2)—and the push for critical hermeneutics of suspicion, identification and retrieval (Habel 2011: 8–14), but i do not belong to the Western scholarly traditions that EBC challenges nor am i on board with the drift towards romanticizing the agency and voices of Earth8 and of its creatures. I read for beasts, for instance, on land and in the sea, but i am mindful that i can only read as a native. Indigenous. Human. In other words, i have boarded the EBC boat because of its principles, but not because of its practices. Those principles are the starting points for this commentary. In other words, i assume but do not look for the ecojustice principles in the Jonah narrative.

So far, i have given the impression that i am an unruly runagate going for a ride on the EBC boat, away from the pride land (read: the commentary business) of biblical scholarship. And at some point, i will jump (fresh) off the EBC boat. At that point, notwithstanding, i will be grateful for the opportunity to also mark possibilities for the “radical re-orientation” of the EBC (as introduced in Habel 2011: 1–16). Key in my attempt at radical re-orientation is the appeal to the realities and imageries of natives of the sea and of (is)lands. Herein is one of the contributions of this EBC volume to the study of Jonah: analysing Jonah with native, sea and (is)land orientations (on islander criticism, see Havea, Aymer and Davidson 2015; Havea 2018b).

Hermeneutical rip

The hermeneutics of suspicion, identification and retrieval work well if they are stimulated to intersect, so that they are not three steps in a linear process but that they become like curls in a rip. In this hermeneutical rip there needs to be a point of entry but one might end up at a different place than planned. Several scenarios are possible with the intersection of the three critical hermeneutics: suspicion could open the way for identification and retrieval, identification could set the tone for retrieval and suspicion, retrieval could require and at once invite identification and suspicion and so on. One may of course enter from two or more points bearing in mind, for instance, that suspicion against one subject may incite suspicion against other subjects, and the same applies in the case of identification and retrieval.

In the EBC hermeneutical rip, the objects of suspicion, identification and retrieval are many. For instance, hermeneutics of suspicion against anthropocentrism may be coupled with suspicion against dualistic views that see Earth as object for human interests, against linear ways of thinking, against the politics of identification, against the supremacism of retrieval missions and against Earth-centred mindsets that ignore the powers of Earth to reject, consume and subjugate. Earth is not impassive nor naïve. Hermeneutics of identification with the ways and place of non-human subjects and interests in biblical texts may...