eBook - ePub

Perseus

Daniel Ogden

This is a test

- 200 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Perseus

Daniel Ogden

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The son of Zeus, Perseus belongs in the first rank of Greek heroes. Indeed to some he was a greater hero even than Heracles. With the help of Hermes and Athena he slew the Gorgon Medusa, conquered a mighty sea monster and won the hand of the beautiful princess Andromeda. This volume tells of his enduring myth, it's rendering in art and literature, and its reception through the Roman period and up to the modern day.This is the first scholarly book in English devoted to Perseus' myth in its entirety for over a century. With information drawn from a diverse range of sources as well as varied illustrations, the volume illuminates the importance of the Perseus myth throughout the ages.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perseus è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Perseus di Daniel Ogden in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a History e Ancient History. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

KEY THEMES

2

THE FAMILY SAGA

THE FAMILY SAGA ON STAGE

It was in the tragedies of Classical Athens that Perseus’ family saga received its most influential elaboration. Prior to this, it had been known that Zeus had fathered Perseus by Danae since at least ca. 700 BC: ‘I fell in love with Danae of the fair ankles, the daughter of Acrisius, who bore Perseus, distinguished amongst all warriors’, the god declares in the Iliad (14.319–20). And Perseus had been enmeshed in the remainder of what was to become his familiar genealogy by at least the mid-sixth century BC ([Hesiod] Catalogue of women fr. 129.10–15 and fr. 135 MW, Stesichorus fr. 227 PMG/ Campbell). The comic playwright Menander, writing at the end of the fourth century BC, implies that Zeus’ corruption of Danae had by then become a hackneyed theme on the tragic stage: ‘Tell me, Niceratus, have you not heard the tragedians telling how Zeus once became gold and flowed through the roof, and had adulterous sex with a confined girl?’ (Samia 589–91).

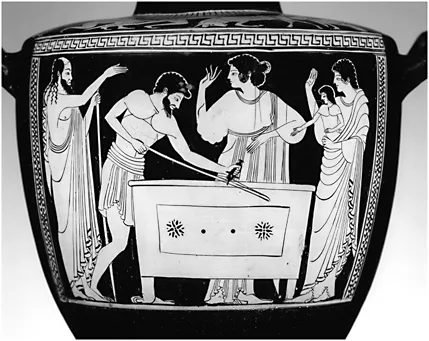

Aeschylus devoted a trilogy of tragedies to Perseus and his family. We know that two of these were named Polydectes (TrGF iii p. 302) and Phorcides (i.e. ‘Graeae’, frs 261–2 TrGF). But substantial fragments survive only from the accompanying satyr-play, the Dictyulci Satyri (‘Net-dragging Satyrs’, frs 46a–47c TrGF), which dealt with Dictys’ retrieval of Danae and Perseus from the sea in their chest. There have been speculative attempts to date this group of four plays by associating them with flurries of scenes on pots. One theory, which conjectures that the unidentified play focused on Danae and Acrisius, associates the group with the ca. 490 flurry of scenes of Acrisius’ enclosure of Danae and Perseus in the chest. Another theory associates the group rather with the ca. 460 flurry of scenes of Dictys releasing Danae and Perseus from the chest and introducing them to Polydectes, and of scenes of the Graeae. There is a striking variation in the representation of Perseus’ age and size on these vases. He can range from being a babe in arms (e.g. LIMC Akrisios no. 2 = Fig. 2.2, Danae no. 48), to quite a grown lad (e.g. no. 54). We recall that Pherecydes makes Perseus three or four years old before his discovery (FGH 3 fr. 26 = fr. 10, Fowler).1

Sophocles (floruit 468–06 BC) wrote an Acrisius (frs 60–76 TrGF), a Danae (frs 165–70 TrGF), and a Larissaeans (frs 378–83 TrGF). Amongst the fragments of the Acrisius, we find justifications of the king’s behaviour, perhaps at the point at which he first imprisons Danae, and perhaps from his own mouth: ‘No one loves life like an old man’ (fr. 66) and: ‘For to live my child, is a sweeter gift than anything, for it is not possible for the same people to die twice’ (fr. 67). Amongst the fragments of the Danae we may find Acrisius’ voice in the phrase, ‘I do not know about the rape. But one thing I do know is that I am done for if this child lives’ (fr. 165). The Larissaeans dealt with Perseus’ accidental killing of Acrisius in Larissa. A fragment of this play suggests that it was Acrisius himself that was here laying on the games (fr. 378), in contrast to the Teutamides of the Apollodoran account (Bibliotheca 2.4.4), and so that he had somehow contrived to make himself king of the city. In another fragment Perseus himself explains what had caused him to misthrow the discus that was to kill his father: ‘And as I was throwing the discus the third time Elatos, a Dotian man, caught hold of me’ (fr. 380).2

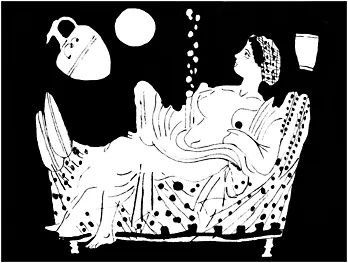

Figure 2.1 The impregnation of Danae.

Euripides’ Danae (frs 316–330a TrGF), probably produced between 455 and 428 (TrGF v.1 p. 372), dealt with Danae’s impregnation by Zeus and enclosure in the chest (Malalas p. 34 Dindorf). Acrisius evidently lamented his sonless state, and his postponement of the siring of children until old age (fr. 316–17). The observation that women are hard to keep under guard presumably refers, somehow, to Danae’s incarceration (fr. 320). Euripides’ Dictys of 431 BC (frs 330b–48 TrGF), perhaps illustrated on vases (LIMC Danae no. 7, Polydektes no. 6), seems to have dealt with Polydectes’ persecution of Danae and Dictys after Perseus had been sent off against the Gorgon. Perhaps they fled to altars for protection, as in the Apollodoran account (Bibliotheca 2.4.2–3; cf. Theon on Pindar Pythians 12 at P.Oxy. 31.2536.). One fragment appears to preserve Dictys’ attempt to console Danae, who believes Perseus to be dead (fr. 332).3

Figure 2.2 Acrisius has the chest prepared for Danae and baby Perseus.

We can probably access another, unidentifiable but radically different tragic treatment of the saga through the work of the second-century AD mythological compiler Hyginus. He preserves for us a version of the family saga wholly at odds with all other accounts. His action proceeds largely as normal until Danae and Perseus have been enclosed in the chest:

By the will of Zeus she was brought to the island of Seriphos. When the fisherman Dictys discovered them, breaking open the chest, he found the woman with her baby, and he took them to king Polydectes. Polydectes married her and reared Perseus in the temple of Athena. When Acrisius learned that they were staying with Polydectes, he set out to find them again. When he had arrived there, he begged Polydectes for them. Perseus promised Acrisius that he would never kill him. When Acrisius was held back by a storm, Polydectes died. Whilst they were holding funeral games for him, Perseus threw a discus and the wind carried it off onto the head of Acrisius, and he killed him. And so the gods accomplished what he had not intended. Acrisius was buried, and Perseus set out for Argos and took possession of his grandfather’s kingdom.

(Hyginus Fabulae 63)

Elsewhere Hyginus specifies that it was Perseus himself who established the funeral games for his foster-father Polydectes (Fabulae 273.4). This account obviously represents a complete reconfiguration of the traditional story. Dictys, the Gorgons, Andromeda and the kētos adventures have been completely extruded (although Athena stays on as Perseus’ protector). Polydectes has been transformed from wicked predator into benign protector (cf. Scholiast Homer Iliad 14.319; ‘Scholiasts’ are commentators on ancient texts, and wrote in the Hellenistic, Imperial and Byzantine periods), and actually marries Danae. Acrisius then of his own accord seeks after Perseus, seemingly because he has had a change of heart. This curious narrative probably derives from a Classical tragedy: it has a distinctively tragic flavour and Acrisius may well have been dragged to Seriphos in part because of the genre’s unity-of-place requirement.

The Greek tragedies shaped the tragedies of early Latin literature on similar subjects. In the third century BC both Livius Andronicus (p. 3, Ribbeck3) and Naevius (pp. 7–9, Ribbeck3) wrote Danae tragedies, but the fragments can tell us nothing of their action, other than that Naevius’ play included the unsurprising detail of a ‘ruddy shower of gold’ (fr. 5).

We can reconstuct little of comic poets’ responses to the family-saga part of Perseus’ adventures. Amongst the remains of fifth-century BC Old Comedy the single surviving fragment of Sannyrio’s Danae promisingly gives us Zeus deliberating whether he should get through the hole to gain access to Danae by transforming into a shrew-mouse (fr. 8 K–A). Of Apollophanes’ Danae we have only the name (T1 K–A). The surviving fragments of Cratinus’ Seriphians of ca. 425 (frs 218–32 K–A) suggest that it focused on Perseus’ return to Seriphos, since Andromeda is referred to as ‘a baited trap’, presumably for the sea-monster, but perhaps for Perseus (fr. 231). Since the demagogue Cleon was ridiculed in the play for his terrible eyebrows and indeed his insanity, he may have appeared in the role of the Gorgon (fr. 228). We have just a hint of the action of Eubulus’ Danae, a Middle Comedy of the earlier fourth century. In its single fragment a woman, no doubt Danae, complains of rough treatment from a man, no doubt Acrisius (fr. 22 K–A).4

THE IMPREGNATION OF DANAE

Pherecydes is the earliest source to describe Zeus’ access to Danae in any detail. He implies that Zeus, presumably the Zeus whose altar sat in the courtyard above, transformed himself into golden rain merely for the purpose of getting through the skylight, but then reverted to humanoid form in order to have sex with the girl (Pherecydes FGH 3 fr. 26 = fr. 10, Fowler). It is reasonable enough that Zeus should have shown himself to Danae in humanoid form at some stage, because she needed to know who had impregnated her. But the remainder of the literary sources imply that Zeus retained the form of golden rain to flow directly into Danae’s loins, as a sort of golden sperm, as in a passing reference in Sophocles’ Antigone: ‘she took in store the gold-flowing seed of Zeus’ (944–50). And this indeed is the way the artists liked to portray the scene, with a shower of golden rain heading straight for Danae’s lap (LIMC Danae nos. 1–39, the earliest of which dates from ca. 490 BC). But for all that he impregnated her in the form of pure seed, Danae was evidently not denied sexual pleasure in the congress. In many images, from the mid-fifth century onwards, she actively welcomes the seed into her lap by holding her dress out of the way to receive it (LIMC Danae nos. 7, 8, 9 [= Fig. 2.1], 19, 26, 33), or alternatively uses the fold of her dress to collect it (LIMC Danae nos. 5, 10, 12, 31). In some her head is actually thrown back in ecstasy (note especially the mid-fourth-century BC chalcedony intaglio, LIMC Danae no. 11).5

Latin sources add some interesting touches to Danae’s confinement. Horace transforms her subterranean bronzed dungeon into a bronze tower (Odes 3.16.1–11, ca. 23 BC). This notion was to be a popular one in Latin literature and the later western tradition. Ovid makes the nice point that it was Danae’s very confinement that fired Zeus’ passion for her (Amores 2.19.27–8, ca. 25–16 BC). The Vatican Mythographers preserve the intriguing idea that Danae was watched over by girl guards – for obvious reasons – and dogs (First Vatican Mythographer 137 Bode = 2.55 Zorzetti, Second 110 Bode).

THE CHEST AND ITS MYTHOLOGICAL COMPARANDA

The tale of Perseus and Danae fits broadly into a widespread folktale pattern. According to this, a prophecy warns of danger should a king or queen produce a son. Despite attempts to ensure that no such child should be born, it is produced nonetheless and so exposed in a container either by land or, more usually, on water. The child is found and reared by a humble person or even an animal. On coming to manhood the child distinguishes himself and does indeed kill his father, be it by accident or design. With a few qualifications, a great many well-known heroic birth-myths can be fitted into this pattern: from the Greek world itself those of Oedipus, Heracles, Paris, Telephus and the tyrant Cypelus; from the Roman world that of Romulus; from the Near East those of Gilgamesh, Sargon of Akkad, Cyrus, Moses and even Jesus; from India that of the Mahabharata’s Karna; and from the Germanic world that of Tristan.6

But it is the Greek myth of Auge and her son Telephus that provides a particularly close parallel for Perseus’ sea-ordeal. The tale, in one of its most canonical forms, and seemingly the one in which it was already told by Hecataeus at the beginning of the fifth century BC, proceeded as follows. Aleus, king of Tegea in Arcadia, was told by Delphi that a son of his daughter Auge would one day kill his (Aleus’) sons, one of whom was Cepheus. To ensure that Auge would not bear a son, Aleus appointed her priestess of Athena, in which role she was bound to remain a virgin. But she was corrupted by Aleus’ guestfriend Heracles in the sanctuary itself, either in a single drunken act of rape, or in repeated consensual but clandestine congress, with a pregnancy resulting. She initially hid the baby, Telephus, in the sanctuary, but the desecration of the sanctuary inflicted a sterility upon Tegea which ultimately resulted in the child’s discovery. Aleus forced Auge to swear to the identity of the baby’s father, but when she did so, truthfully, he did not believe her. He then gave mother and baby over to Nauplius to dump in the sea in a chest, which he duly did. They were carried ashore in Mysia, where they were welcomed by king Teuthras, who married Auge and adopted Telephus. In due course, Telephus did indeed kill Aleus’ sons, although we are told nothing of the circumstances in which this occurred.

There are two principal variants. In one, Auge’s violation was detected whilst she was still pregnant and it was as Nauplius was taking her off to the sea that she gave birth to her baby suddenly on Mt Parthenios (or Parthenion), ‘Mt Virgin’. She hid him in a thicket, later destined to become the site of his sanctuary, where he was nurtured by a doe, thus acquiring the name Telephus (Tēlephos, supposedly from thēlē, teat, and elaphos, deer). He was then rescued by shepherds and reared by one Corythus. In the other variant tale, Nauplius’ conscience got the better of him and he refrained from putting Auge and Telephus in the sea, and rather sold them on, directly or indirectly, to Teuthras. (See Hecataeus FGH 1 frs 29a, 29b, Aeschylus Mysians, Telephus, Sophocles Mysians, Euripides Auge frs 264a–281 TrGF and Telephus frs 696–727c TrGF, Alcidamas Odysseus 14–16, Diodorus 4.33.7–12, Strabo C615, Apollodorus Bibliotheca 2.7.4, 3.9.1, Pausanias 8.4.9, 8.47.4, 8.48.7, 8.54.6, 10.28.8, Tzetzes on [Lycophron] Alexandra 206. Rather different versions of this saga are found at Hesiod Catalogue of Women fr. 165 MW, Hyginus Fabulae 99–100, 244 and Aelian Nature of Animals 3.47.7)

Many parallels with the Perseus—Danae narratives are evident: Delphi foretells that a daughter’s son will kill kin; her father acts to ensure that she remains a virgin; but she is violated by Zeus or his son; she attempts to conceal the baby; the baby is reared in a temple of Athena; the baby is discovered; the girl swears truthfully to the identity of the baby’s father, but is not believed; she is dumped in the sea in a chest with the baby; the pair are brought ashore where they are rescued by a kindly man who looks after them. But there are other links with the Perseus tradition too, in the form of shared personnel. Most noteworthy is the participation of Cepheus, who was evidently at one time identical with the Cepheus who became Perseus’ father-in-law (see chapter 5). We learn from Apollodorus that Aleus’ sister Sthenoboea was married to Perseus’ great uncle Proetus (Bibliotheca 3.9.1). And the name of Teuthras curiously recalls that of Teutamides of Larissa, host to Acrisius and Perseus (Apollodorus Bibliotheca 2.4.4).8

Two further Greek parallels may be noted. A similar tale was also told of Semele and Dionysus by the people of Brasiae:

The people there say, although they agree with no other Greeks in this, that Semele bore the child she conceived from Zeus. She was detected in this by Cadmus and both she herself and Dionysus were cast into a chest. They say that the chest was carried by the waves to their land, and that they gave Semele a splendid burial (for she was no longer alive when they found her), but they reared Dionysus. ...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series foreword

- Acknowledgements

- List of illustrations and credits

- Abbreviations

- Ancient authors and fragments

- WHY PERSEUS?

- KEY THEMES

- PERSEUS AFTERWARDS

- Notes

- Further reading

- Bibliography

Stili delle citazioni per Perseus

APA 6 Citation

Ogden, D. (2008). Perseus (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1508092/perseus-pdf (Original work published 2008)

Chicago Citation

Ogden, Daniel. (2008) 2008. Perseus. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1508092/perseus-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Ogden, D. (2008) Perseus. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1508092/perseus-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Ogden, Daniel. Perseus. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2008. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.