![]()

Introduction

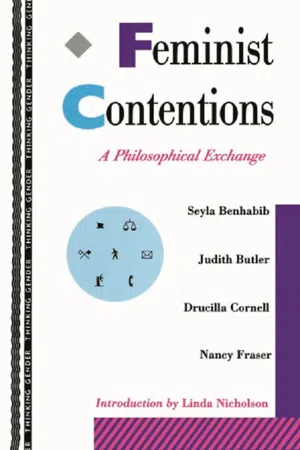

Linda Nicholson

This volume is a conversation among four women, originating in a symposium organized by the Greater Philadelphia Philosophy Consortium in September 1990. The announced topic was feminism and postmodernism. The original speakers were Seyla Benhabib and Judith Butler with Nancy Fraser as respondent. The selection of this particular group was not accidental. While these three theorists had much in common—a well-established body of writing in feminist theory influenced by past work in continental philosophy—these three were also noted for relating to this topic in different ways. This conjunction of similarity and difference combined with the reputation of each as a powerful theorist seemed to ensure a noteworthy debate. And because that was the consequence, the papers of the symposium were published in the journal Praxis International (11:2 July 1991). Following this publication, a decision was made to extend the discussion: to include a contribution from Drucilla Cornell, to have each of the now “gang of four” responding to each other’s original paper, and to publish the whole as a book. The volume was first published as Der Streit um Differenz (Frankfurt: Fischer Verlag, 1993). This volume marks the appearance of a somewhat altered version of this collection in English.

The above depicts only some of the structural features of this volume; it provides the reader with no sense of its content. But articulating the content of this volume is a particularly challenging task, for reasons best understood through considering a few things the volume is not. For one, this volume is not an anthology on the present state of feminist theory. In 1995, for a collection of essays and responses written by four white women from the United States who come out of a certain tradition within a particular discipline to claim to represent “feminist theory” would represent a kind of arrogance each of these women would vehemently reject. Consequently, this volume makes no claim to provide any kind of overview on contemporary feminist theory. Nor even does it claim to provide a state-of-the-art discussion of “the relationship of feminism and postmodernism.” Though the phrase “feminism and postmodernism” was used to advertise the original symposium, disagreement soon emerged over the usefulness of the term “postmodernism” as each differently put forth her views on how the discussion should best be described. Thus, a major source of the difficulty I, as introducer, face in telling you, the reader, “what this volume is about” is that partly defining this discussion are differing views on “what this discussion is about.” In this respect, this volume is not like an anthology where the topic has been determined in advance and where each of the contributors is asked to speak on it. But this distinctive feature of this volume, combined with the complexity and richness of the ideas expressed, makes any attempt at abstract characterization of the subject matter of this volume problematic, particularly before you, the reader, have any sense of what the authors themselves are saying. Consequently, before I interject my own perspectives on “what this volume is about,” let me first provide some brief summarizations of the initial contributions.

Benhabib responded to the original symposium theme by situating the relation of feminism and postmodernism within broader cultural trends. For Benhabib, the present time is one in which some of the reigning traditions of western culture are being undermined. While Benhabib sees much about these traditions which need to be abandoned, she also views some formulations of this overhaul as eliminating too much. Consequently, a major purpose of her original essay was to separate out that which feminists ought to reject from that which we need to retain. Borrowing from Jane Flax’s claims about certain key tenets of postmodernism, Benhabib elaborates this separation in relation to the following three theses: the death of man, the death of history, and the death of metaphysics. Benhabib argues that all of these theses can be articulated in both weak and strong versions. The weak versions offer grounds for feminist support. However, Benhabib claims that in so far as postmodernism has come to be equated with the strong formulations of these theses, it represents that which we ought to reject.

Thus, from her perspective, it is more than appropriate that feminists reject the western philosophical notion of a transcendent subject, a self thematized as universal and consequently as free from any contingencies of difference. Operating under the claim that it was speaking on behalf of such a “universal” subject, the western philosophical tradition articulated conceptions deeply affected by such contingencies. The feminist take on subjectivity which Benhabib supports would thus recognize the deep embeddedness of all subjects within history and culture. Similarly, Benhabib welcomes critiques of those notions of history which lead to the depiction of historical change in unitary and linear modes. It is appropriate that we reject those “grand narratives” of historical change which are monocausal and essentialist. Such narratives effectively suppress the participation of dominated groups in history and of the historical narratives such groups provide. And, finally, Benhabib supports feminist skepticism towards that understanding of philosophy represented under the label of “the metaphysics of presence.” While Benhabib believes that here the enemy tends to be an artificially constructed one, she certainly supports the rejection of any notion of philosophy which construes this activity as articulating transcultural norms of substantive content.

But while there are formulations of “the death of man”, “the death of history,” and “the death of metaphysics” which Benhabib supports, there are also formulations of these theses which she considers dangerous. A strong formulation of “the death of man” eliminates the idea of subjectivity altogether. By so doing, it eliminates those ideals of autonomy, reflexivity, and accountability which are necessary to the idea of historical change. Similarly, Benhabib claims that certain formulations of the death of history negate the idea of emancipation. We cannot replace monocausal and essentialist narratives of history with an attitude towards historical narrative which is merely pragmatic and fallibilistic. Such an attitude emulates the problematic perspectives of “value free” social science; like the latter, it eliminates the ideal of emancipation from social analysis. And, finally, Benhabib rejects that formulation of “the death of metaphysics” which entails the elimination of philosophy. She argues that philosophy provides the means for clarifying and ordering one’s normative principles that cannot be obtained merely through the articulation of the norms of one’s culture. Her argument here is that since the norms of one’s culture may be in conflict, one needs higher-order principles to resolve such conflict. Also, she claims that there will be times when one’s own culture will not necessarily provide those norms which are most needed. Philosophy again is necessary to provide that which one’s culture cannot.

In general, Benhabib’s worry about the strong formulations of these three theses is that they undermine the possibility of critical theory, that is, theory which examines present conditions from the perspective of utopian visions. Her belief is that much of what has been articulated under the label of postmodernism ultimately generates a quietistic stance. In short, for Benhabib, certain political/theoretical stances—specifically those which are governed by ideals and which critically analyze the status quo in the light of such ideals—require distinctively philosophical presuppositions, presuppositions which are negated by many formulations of postmodernism.

Judith Butler’s concerns, however, are of a very different nature. Butler focuses her attention not on what we need philosophically in order to engage in emancipatory politics, but on the political effects of making claims to the effect that certain philosophical presuppositions are required for emancipatory politics. Such a focus reflects her general inclination to inquire about the political effects of the claims that we make and of the questions that we raise. She points to some of the problems involved in the very question: “What is the relation of feminism and postmodernism?” noting that the ontological status of the term “postmodernism” is highly vague; the term functions variously as an historical characterization, a theoretical position, a description of an aesthetic practice and a type of social theory. In light of this vagueness, Butler suggests that we instead ask about the political consequences of using the term: what effects attend its use? And her analysis of such effects are mixed. On the one hand, Butler sees the invocation of the term “postmodernism” as often functioning to group together writers who would not see themselves as so allied. Moreover, many of its invocations appear to accompany a warning about the dangers of problematizing certain claims. Thus, it is frequently used to warn that “the death of the subject” or “the elimination of normative foundations” means the death of politics. But Butler argues: is not the result of such warnings to ensure that opposition to certain claims be construed as nonpolitical? And does not that in turn serve to hide the contingency and specific form of politics embodied in those positions claiming to encompass the very field of politics? Thus, questions about whether “politics stands or falls with the elimination of normative foundations” or “the death of the subject” frequently masks an implicit commitment to a certain kind of politics.

If Butler sees any positive effects of the use of the term “postmodernism,”—and the term she better understands is “poststructuralism”—it is to show how power infuses “the very conceptual apparatus that seeks to negotiate its terms.” Here her argument should not be interpreted as a simple rejection of foundations, for she states that “theory posits foundations incessantly, and forms implicit metaphysical commitments as a matter of course, even when it seeks to guard against it.” Rather it is against that theoretical move which attempts to cut off from debate the foundations it has laid down and to remove from awareness the exclusions made possible by the establishment of those foundations.

The task then for contemporary social theory committed to strong forms of democracy is to bring into question any discursive move which attempts to place itself beyond question. And one such move Butler draws our attention to is that which asserts the authorial “I” as the bearer of positions and the participant of debate. While not advocating that we merely stop refering to “the subject,” she does advocate that we question its use as a taken-for-granted starting point. For in doing so, we lose sight of those exclusionary moves which are effected by its use. Particularly, we lose sight of how the subject itself is constituted by the very positions it claims to possess. The counter move here is not merely to understand specific “I’s” as situated within history; but more strongly, it is to recognize the very constitution of the “I” as an historical effect. This effect cannot be grasped by that “I” which takes itself as the originator of its action, a position Butler sees as most strikingly exemplified by the posture of the military in the Gulf war. Again, for Butler, the move here is not to reject the idea of the subject nor what it presupposes, such as agency, but rather to question how notions of subjectivity and of agency are used: who, for example, get to become subjects, and what becomes of those excluded from such constructions?

This position, raises, of course, the status of the subject of feminism. Butler looks at the claim that postmodernism threatens the subjectivity of women just when women are attaining subjectivity and questions what the attainment of subjectivity means for the category of “woman” and for the category of the feminist “we.” As she asks: “Through what exclusions has the feminist subject been constructed, and how do those excluded domains return to haunt the ‘integrity’ and ‘unity’ of the feminist ‘we’?” While not questioning the political necessity for feminists to speak as and for women, she argues that if the radical democratic impetus of feminist politics is not to be sacrificed, the category “woman” must be understood as an open site of potential contest. Taking on asserted claims about “the materiality of women’s bodies” and “the materiality of sex,” as the grounds of the meaning of “woman,” she again looks to the political effects of the deployment of such phrases. And employing one of the insights developed by Michel Foucault and Monique Wittig, she notes that one such effect of assuming “the materiality of sex” is accepting that which sex imposes: “a duality and uniformity on bodies in order to maintain reproductive sexuality as a compulsory order.”

Thus, the concerns of Benhabib and Butler appear very different. Where Benhabib looks for the philosophical prerequisites to emancipatory politics, Butler questions the political effects of claims which assert such prerequisites. Are there ways in which the concerns of each can be brought together? Nancy Fraser believes that there are. While Fraser’s original essay was written as a response to the essays of Benhabib and Butler, one can see in it the articulation of a substantive set of positions on the issues themselves. This is a set of positions which Fraser views as resolving many of the problems which Benhabib and Butler identify with the stance of the other.

Many of Fraser’s criticisms of Benhabib’s essay revolve around how Benhabib has framed the available options; Fraser claims that the alternatives tend to be articulated too starkly with possible middle grounds overlooked. In relation to “the death of history,” Fraser agrees with Benhabib’s rejection of the conflict as that between an essentialist, monocausal view of history and one which rejects the idea of history altogether. However, she claims that Benhabib fails to consider a plausible middle-ground position: one which allows for a plurality of narratives, with some as possibly big and, all, of whatever size, as politically engaged. Fraser hypothesizes that Benhabib’s refusal to consider such an option stems from Benhabib’s belief in the necessity of some metanarrative grounding that engagement. Consequently, conflicts between her position and that of Benhabib’s around “the death of history” ultimately reduce to conflicts between the two concerning “the death of metaphysics.”

Whereas Benhabib asserts the need for a notion of philosophy going beyond situated social criticism, Fraser, pointing to the position articulated by her and myself in an earlier essay, questions such a need. Fraser claims that the arguments Benhabib advances for such a notion of philosophy are problematic, since the norms Benhabib states are necessary for resolving intrasocial conflict or providing the exile with a means for critiquing her/his society must themselves be socially situated in nature. Consequently, if what is meant by philosophy is an “ahistorical, transcendent discourse claiming to articulate the criteria of validity for all other discourses,” then social criticism without philosophy is not only possible, it is all we can aim for.

Whereas it is through criticisms of Benhabib’s formulations of the options available around “the death of history” and “the death of metaphysics” that Fraser articulates her own position, it is through criticisms of Butler’s formulation of the options available around “the death of the subject” that Fraser’s ideas on this topic come forth. She agrees with Butler that to make the strong claim that subjects are constituted, not merely situated, is not necessarily to deny the idea of the subject as capable of critique. However, Fraser believes that there are aspects of Butler’s language, particularly, her preference for the term “re-signification” in lieu of “critique,” which eliminates the means for differentiating positive from negative change. Fraser sees the need for such differentiation in relation to several positions she views Butler as adopting from Foucault: that the constitution of the subjectivity of some entails the exclusion of others, that resignification is good and that foundationalist theories of subjectivity are inherently oppressive. As Fraser questions: “But is it really the case that no one can become the subject of speech without others being silenced? … Is subject-authorization inherently a zero-sum game?” She notes that foundationalist theories of subjectivity—such as the one of Toussaint de l’Ouverture—can sometimes have emancipatory effects. Fraser believes that being able to differentiate the positive from negative effects of re-signification, processes of subjectification and of foundationalist theori...