![]()

1

Why Do Theorists Say Associations Are Crucial for Democracy?

In American society, the volunteer has long been a nearly sacred figure, and the voluntary civic association has been seen as a cure for nearly all social problems. This chapter will describe these hopes. But do not be lulled by this chapter’s story of civic association as a cure-all. The rest of the book will describe ways that these cures can go wrong.

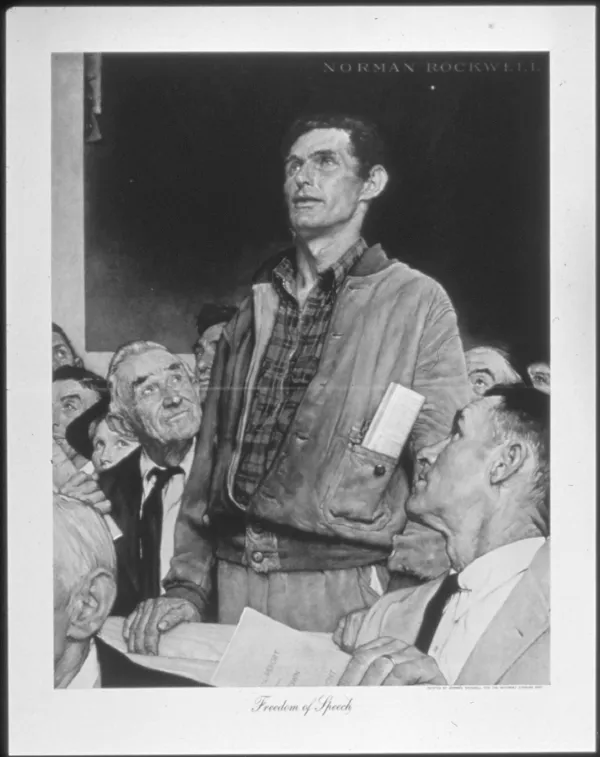

The painting overleaf shows a heroic image of the civic participant – if civic engagement were a religion, this painting could be our icon. Why? It gives us an image of ourselves that highlights some of our core ideals: egalitarianism and individualism. The speaker is obviously a worker, with roughened hands and a plain brown jacket, and yet, the suits listen attentively and respectfully. By participating in this meeting, the suits and the plain folks will learn to listen to one another, develop mutual respect and a feeling of fellowship as they work together. They are convinced that their decision will have an effect on something important.

To understand this faith, many superb studies survey its multiple sources in American culture and in Western culture more broadly, but this book will take a different approach. We will pour ourselves inside three key thinkers and see the world through their eyes. I chose these three because they represent very different perspectives on civic engagement’s place in society.

Writing in the 1830s and 1840s, Alexis de Tocqueville was amazed at Americans’ peppy participation in small, local civic associations that did things like build roads and hospitals. A hundred years later, Jane Addams, experiencing the bewildering diversity and sprawling complexity of early twentieth-century Chicago, saw an urgent need for this tradition of civic engagement to continue, but to transform, to address the problems of a society that had changed since Tocqueville’s era. Addams’ own volunteer work ended up being most effective when she pressured the state, for programs like workplace safety regulations (when there were almost none), sanitation (when garbage pick-up was not routine), playgrounds (she helped invent the concept!), parks, schools, and laws mandating decent wages. At around the same time as Addams, another activist and theorist, Emma Goldman (2006), was writing about workers’ self-run businesses in Spain and elsewhere, describing the possibilities for personal and social transformation in them. To her mind, volunteers who meet after-hours, after work, to figure out how to establish garbage pick-ups or parks are missing the point. The main problem, Goldman says, is that most people lack decision-making power when they are at work, and have little control over the economy. Without dramatic changes in the way we earn our daily bread, volunteering, she implies, will always just be a band-aid stuck onto a gaping wound. Here are three very different portraits of civic engagement, focusing on three different corners of a big canvas. Our three authors do have some grounds for agreement: they all insist that people are not born good citizens; they need to learn how to be good, and the forms of association that these writers describe are the informal “schools” for it. Readers who already are familiar with this map might skim or skip this chapter. The historical background is worth understanding, though, and the arguments continue to this day, though, so we begin with Tocqueville.

Norman Rockwell’s Freedom of Speech (from the series Four Freedoms), 1948. Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, MA.

The Iconic Figure and Tocquevillean Volunteering

Tocqueville’s story about “America” is partly an historical observation and partly a projection of his own hopes and fears. Tocqueville, who came from an aristocratic French family, was both intrigued and terrified by the idea of democracy, but saw that this idea was gathering momentum, poised to take over the earth. From his voyage to America, he concluded that without grassroots civic associations democracy would collapse, and a disorganized, fearful, lonely, hot-headed, small-minded, and mean-spirited population would rule.

Tocqueville has a practical agenda here, not just a theory. He is interested in stacking luck’s deck, so that no matter what innate intelligence or generosity people have at birth, social conditions can sway the game. He has very little faith in people’s innate decency. People are not born good citizens or bad citizens, good or bad people, caring or uncaring, selfish or altruistic, greedy or generous, passive or active, Tocqueville says. Their societies train them to be good or bad, in very small, constant, steady, everyday ways: the steady constant drip drip drip that creates canyons and valleys, not a big, one-time splash. “Common sense” tells us that good people create a good society, but Tocqueville reverses the arrows: a good society creates good individuals. Intuitively, this makes sense: a decent society is more likely to produce decent individuals than a war-like, mean-spirited, vicious society is. In saying this, he could be dubbed the world’s first sociologist, when he asserted over and over that there is nothing that can clearly be called “human nature” except for our amazing ability to be so incredibly different in different societies.

Tocqueville goes further than this obvious intuition, by specifying the mechanisms that create good or bad people and societies. He says that in democracies, civic associations both make individuals better and improve society as a whole. What is so potentially terrifying and potentially inspiring about Tocqueville’s story about democracies is that he says that creating good citizens who are capable of good self-rule requires a whole way of life, not just a civics class in high school or a vote every four years. He says that participating in associations offers people cognitive, emotional, and political benefits.

Knowledge – cognitive benefits:

Participants develop decision-making skills, skills in creating an organization, and knowledge about how organizations operate. Society benefits. In associations, people conduct open-ended discussions about political issues. Informal deliberation helps them think up better solutions than they would if they were just thinking all by themselves.

Solidarity – emotional benefits:

Participants develop fellow feeling for one another. They learn to take each others’ interests into account, to keep asking, “what’s good for society as a whole?” and to compromise. Society benefits. Associations can develop support networks for anyone who becomes needy.

Power – political benefits:

Participants learn how to make real changes. Society benefits. Everyone, not just elites, will have a say in decisions about public issues.

So What Could Possibly Go Wrong with Democracy?

Isn’t “democracy” just another word for “good?” According to Tocqueville, no. After portraying this wholesome, uncontroversial image of democracy, he goes on to a terrifying image of democracy gone awry. His worry is this: what if democracy puts government in the hands of majority without constantly training that majority in the arts of self-governance? He gives many good reasons to expect this disaster in democracies, and says that civic associations can prevent most of them.

Fear of attachment and fear of dependence

First, Tocqueville is worried that people in democracies will forget how deeply they depend on one another. For most of the previous thousand years, Europeans had been linked together in a hierarchy, bound in a system of mutual obligation that linked nobles to peasants. Peasants enjoyed many customary rights that made their survival possible: to gather firewood and hunt deer in the nobles’ forests; to graze sheep on the nobles’ land; to be protected, by nobles, from invasion; to be helped by nobles in times of famine and illness (Hobsbawm 1962). Everyone had a set place and a set of customary duties. A long chain of mutual obligation attached rich to poor, parent to child to grandchild, brother to sister, bishop to parishioner, noble to layman. He says, “Aristocracy links everyone, from peasant to king, in one long chain. Democracy breaks the chain and frees each link” (Tocqueville 1968: 508).

This simple couplet evokes a ghost that has been haunting democracies for centuries: if people no longer imagine a solid hierarchy linking all humans to each other, inside a larger “Great Chain of Being,” as medieval Europeans called it, linking angels and deities to humans, on down to worms and fish, nothing would prevent the rich from treating the poor like trash. Without this chain linking everyone and everything together, the universe starts to seem like a warehouse full of spare parts. People who live in most traditional societies are, Tocqueville said, anchored to each other and to the land, whereas “Americans” – who stand in for his somewhat abstract model of “people in a democracy” – frantically dash from one place to another, never settling down long enough to establish deep connections, always striving for something better before they have had time to enjoy what they already have. Such people could just use each other, and society could become a big machine that spit people out when they were used up.

After democracies break these rigid, secure, built-in attachments up and down the hierarchy, people might just imagine themselves as totally detached from one another, as if they held their entire fate in their own hands.

Such folk [people in a democracy, as opposed to an aristocracy] owe no man anything and hardly expect anything from anybody. They form the habit of thinking of themselves in isolation and imagine that their whole destiny is in their own hands. (Tocqueville 1968: 508)

This is a big peril to democracy, says Tocqueville. Like the good proto-sociologist that he was, he says that this belief, that one can cut oneself off from society and be completely self-sufficient, is simply incorrect. He urgently repeats, over and over, that no one can live outside of the web of relationships. People need each other, not just for material goods, but also for a sense of self, and an emotionally coherent life. Imagining that you can cut yourself out of the web simply prevents you from understanding yourself, he says. To understand your real, everyday life conditions is inseparable from understanding who you are.

Some Americans still imagine that they could survive on their own, without any help from “outsiders” like the government, even though we all know, realistically, that even our water comes from hundreds of miles away. Some websites and books, for example, teach people about “living off the grid.” Tocqueville, were he reborn today, might wryly observe that they were written on computers that were probably made in China, while the writers were eating Costa Rican bananas, and drinking water that was not poisonous because the government prevented a factory upstream from polluting it. When people stop acknowledging their inevitable connection to one another, they stop making sure that their world is livable together, and democracy vanishes.

What can prevent this first peril from taking hold? Civic associations come to the rescue! Making decisions in local associations gives ordinary people a vision of the big picture, showing them how they are inevitably part of a great chain. But here, in democracies as opposed to other societies, making the “chain” is supposed to be conscious, and each individual is supposed to have a voice and a choice. Local civic associations bring decision-making down to the reach of the average, unexceptional person – even someone who does not have a special fondness for political affairs.

It is difficult to force a man out of himself and get him to take an interest in the affairs of the whole state, for he has little understanding of the way in which the fate of the state can influence his own lot. But if it is a question of taking a road past his property, he sees at once that this small public matter has a bearing on his greatest private interests, and there is no need to point out to him the close connection between his private profit and the general interest. [but a direct translation of the end from the original French is: “… and he will discover, without anyone’s showing him, the tight connection between his particular interest and the general interest.”] (Tocqueville 1961: 150–1, my translation)

When this fellow joins the association to decide where to build the highway, he bridges a gap between personal experience and politics. He will understand how he depends on other people. Participating in local decision-making, in a civic association, will also prove to him the value of cooperation. Whereas democratic societies tend to give people the false impression that they are entirely independent of one another, working together in associations shows them how much more effective they are when they work together. It would be silly, for example, if the highway only went in front of this individual’s house, but then ended a block later. This fellow might learn to compromise, to say “We will start by paving ten streets across town first, and then start paving the street near my house when we’ve finished.” This was what participants in a “participatory budget” process decided, in a Brazilian city in the early 2000s (Baiocchi 2002). (We will come back to this in chapter 6.) Participants learned that a rising tide raises all boats. This is Tocqueville’s concept of “self-interest rightly understood.” If the man with the highway were alive today, he might support environmental protection so that he could have clean water, even if it means that he could not dump his own sewage in the nearby river. It is not heroic, not even really altruism, but a simple recognition that always fighting for one’s own immediate interests is often self-defeating.

Tyranny of the majority

When democracy “breaks the chain and frees each link,” a second potential peril to democracy arises: it is hard for citizens to learn how to link themselves back together. Instead of joining in open-ended, reasonable associations, they might form a “tyranny of the majority.” Each link, in this metaphor, is like a speck of flour, blowing whichever way the wind blows; with just a drop of water, the little specks of flour might glue themselves together too tightly and massify (Tocqueville 1968: 433). Mob rule, witch hunts, and fanaticism set in.

A “tyranny of the majority” is more potent than a monarch’s power. A king’s power is centralized in one place, but a lot can go on behind the king’s back. In a democracy, in contrast, “… all the parties are ready to recognize the rights of the majority because they all hope one day to profit themselves by them” (Tocqueville 1968: 248). Each individual is a “ruler” of sorts. Eyes are everywhere. In contrast, “… no monarch is so absolute that he can hold all the forces of society in his hands, and overcome all resistance, as a majority invested with the right to make the laws and to execute them” (Tocqueville 1968: 254). If a person in a democracy disagrees with the majority’s opinions, where can he or she turn? There are no other powers to which to turn; there is almost nothing outside of the majority.

Imagine the person who does not agree with the majority, or can’t conform. If a “tyranny of the majority” develops, the whole society turns into one interminable seventh-grade class in the 1950s, before there were rules against harassment, and you are the gay thirteen-year-old who thinks you are the only one of his kind on the planet. “When once its mind is made up on any question, there are … no obstacles which can retard, much less halt, its progress and give it time to hear the wails of those it crushes as it passes” (Tocqueville 1968: 248). In such conditions, democracy vanishes.

Civic associations to the rescue, again! Where there are plural civic associations, Tocqueville implies, people learn to tolerate opposing views, even if they do not agree with them. For example, there are, in contrast to the 1950s, now civic associations that defend gay rights, so the specks of flour cannot turn into a hard lump and crush their opponents quite as easily. There is somewhere else to turn.

Tocqueville considers this to be one of the most important things that democracy does: protect a space for private decision-making. In his day, the decisions that thinkers like him wanted to make private were about religion, so that the religious wars of his era would end. Now we can add sexuality, and a whole host of other freedoms. Often, we protect them with voluntary associations, as the gay rights example illustrates. And then, they become topics of debate, regarding just how private they really should be. Your child-raising practices generally are nobody’s business but your own, but if they include abuse, they are someone else’s business, for example. We all can publicly debate the possibility of leaving decisions in private hands. This isn’t possible in places that have no associations to conduct the argument. Participating in associations can, in Tocqueville’s mind, prevent people from becoming so hot-headed and passionate, they kill each other over minor, or even major, differences. A person in a civic ass...