![]()

1

HOW TO BEGIN

WHERE TO START

A book can have only one beginning, but campaigns can have many different beginnings. First you need to find your own beginning, and that depends on where you are at:

• If you know your issue but you don’t know exactly what you want to achieve, begin by defining your objective (see Chapter 5, ‘The ambition box’);

• If you need to campaign because you are faced with a known specific problem, and that tells you your objective but you don’t know how to get that changed, then begin with the campaign motivation sequence (this chapter);

• If you have a concern but don’t know how the issue works – the forces and processes behind the problem – then start with issue mapping and gathering intelligence (Chapter 4);

• If you already run a campaign and feel a need to change strategy or tactics, try looking at factors such as resources and assets (Chapter 9);

• If you have an organization that thinks it might like to campaign but is not sure, then step back and examine the bigger picture (Chapter 12), and try locating your approach in the ambition box.

See also the campaign planning star in Chapter 5, which illustrates factors needed in generating a campaign plan and proposition.

WHAT COMMUNICATION IS

The two words ‘information’ and ‘communication’ are often used interchangeably, but they signify quite different things. Information is giving out; communication is getting through. (Sidney J. Harris, American journalist and author)

Good communication isn’t noticed. It’s like good design: we only notice bad design. The London Underground map is often cited as a classic. We don’t notice it because it fits its purpose so well (use it to walk around London, and you find it bears little resemblance to ‘reality’).

Forget old saws such as ‘getting your message across’. Campaigners who focus on ‘sending messages’ will never succeed: they will persuade no one but themselves. Successful communication needs to be two-way: more telephone than megaphone, with the active involvement of both parties.

Real communication, it has been said,1 is rare and involves ‘the transferring of an idea from the mind of the sender to the mind of the receiver’.

If someone does not want to receive your message, they won’t. Would-be communicators therefore need to understand the motivations of their audience.

All too often, communication is treated as a technical, one-way process beautifully designed to reflect the views of the sender, unsullied by the need to be effective with the receiver.

‘Delivering messages’, ‘sending information’, ‘targeting advertising’: it becomes like targeting missiles – fire and forget – except that forgetting is the last thing that should be happening. Campaigners should spend at least as much time listening to the public and the target, allies and opponents they seek to influence as they spend in working on communications back in the office.

The word ‘audience’ wrongly implies that receivers are passive. A dialogue is usually best, and if that’s impossible, repetition may succeed in ‘reaching’ the audience.

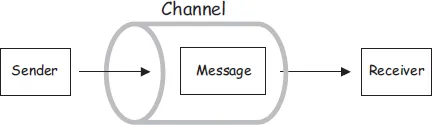

A popular basic model of communications is illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Basic model of communications

We all know that serious misunderstandings can occur even in one-to-one communication. Introduce a third party – such as a newspaper or radio station and its journalists – and volume may increase but noise gets into the channel because of journalists’ interpretations, or pollution by the thousands of other messages to which we are exposed each day.2

To improve communication, obtain feedback, whether volunteered or obtained through qualitative research.

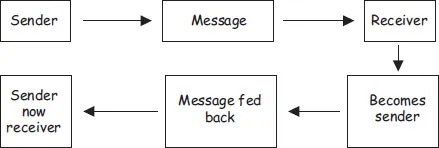

Figure 1.2 Communication model incorporating feedback

Des Wilson, founder of Shelter, said: ‘Remember, the bigger the audience, the simpler the message.’3 So with public media, messages need to become simpler, compared to the complexities you can deal with in conversations at home or in the office.

IF YOU FIND A FIRE

The short words are best, and the old words are the best of all.

(Sir Winston Churchill)

Motivational communication follows some well-established sequences, developed and refined by generations of salespeople. A useful version for campaigns is:

awareness → alignment → engagement → action

Take the example of a fire safety notice that you might find in a hotel.

These notices keep it simple. They look something like the example shown in Figure 1.3 (overleaf). At first sight, constructing this message seems easy but, in fact, it is carefully designed. It instructs to raise the alarm first – this is in the best interests of the hotel residents. It doesn’t say ‘call the fire brigade’ – which might be in the best financial interests of the hotel owner, but which could mean searching for a phone in smoke-filled corridors. It puts lives over property. Then it says to go to the place of safety – and only then call the fire brigade.

So it’s communication with a purpose (here = save lives). You need to know why you are trying to communicate, what the objective is in terms of an action, what you want someone to do, before you can communicate effectively.

Also, the sign is very simple and it instructs rather than offering a discussion, which would not be appropriate in an emergency. It is unambiguous. Lastly, it follows the sequence shown in Table 1.1.

IF YOU FIND A FIRE

1. Raise the alarm

2. Go immediately to the place of safety

3. Call the fire brigade

Figure 1.3 Example of a fire safety notice

Table 1.1 Sequence followed by fire safety notice

| If you find a fire | Awareness |

| We are all in danger | Alignment |

| Let’s go this way | Engagement |

| We are leaving | Action |

Awareness establishes the subject. Alignment establishes that it is relevant to everyone. Engagement is an appeal to join in – and requires a commonly available mechanism (see Chapter 2). The action is what is needed. Omit or reorder any of these steps and problems result.

If all our communication was so simple, we’d all be more effective. Yet all too often our communication is not like this but more like the alternative fire sign shown in Figure 1.4.

IF YOU FIND A FIRE

1. Network with your neighbours

2. Explain the issues and the processes of ignition, fuel effects, oxidation and ion plasmas, and address the social and economic justice dimensions

3. Educate decision-makers regarding the establishment of an adequately resourced fire brigade and fire-prevention culture, and ask your neighbours to join in

Figure 1.4 Alternative fire safety notice

This addresses the same subject: it, too, is about fire. It’s ‘on message’. But it is not very clear and would probably lead to people frying in their rooms. It is a message about an issue, not communication designed to get a result in terms of a specific action. It invites ‘education’ and ‘networking’: things that involve reflection and discussion, and are open to interpretation. This can occur when:

• An internal agenda is transmitted to the outside world – easily done if exhausted by getting it through the system;

• A policy or plan is transmitted as a ‘message’;

• Everyone has a say and the message mentions every important issue; or

• There is an attempt to educate rather than to motivate.

MOTIVATIONAL CAMPAIGN SEQUENCE

Many of the best campaigns are planned as a simple chronology of events. Often there are only one or two fixed dates and the rest is a chain of objectives that need to be reached, like climbing from one level to another or stepping from one stone to the next, with no firm way of predicting just when that will occur.

Plan backwards from the call to action. That should be either a fixed date (such as an event) or a date that can be estimated sufficiently well to have all the necessary communications, assets and capabilities in place when it arrives. The possible start date is then generated by adding together the critical time periods needed for each stage before the call to action opportunity.

Campaigns usually need to start with awareness. Awareness of the problem, preferably made more compelling by showing the victim.4

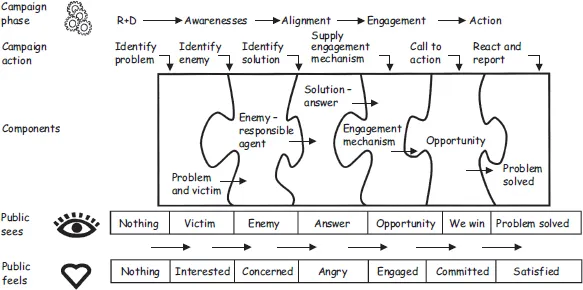

The campaign sequence5 illustrated in Figure 1.5 shows how to plan using the basic formula of the fire notice: awareness → alignment → engagement → action. Each part needs to fit to the next like a jigsaw – the ‘enemy’ needs to be the particular one that fits with that victim, the solution really does have to solve the specific problem, and so on.

Figure 1.5 Motivation sequence campaign model

So in this classic communication path, the story begins when we see the problem – we see ‘victims’. These might be human or physical, or animal or even plants. Fish dying from pollution, or a building damaged by acid rain, for example, or someone suffering torture. This is the awareness-building phase.

Next we see what or who is responsible, the ‘enemy’ or causal agent that is to blame – with no cause, a problem is not an issue. This is followed by a period of reinforcement by repetition or ‘demonization’: former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was an expert at this; she demonized striking miners, for example. This phase ought to last until the problem is established in the mind of our audience. By this time the public state of mind is one of concern.

If the ‘bad news’ just continues, the audience gets fed up and withdraws or switches off – the problem is just another tragedy. Concern with no solution will lead to withdrawal; with no constructive outlet it will create frustration, most probably towards the messenger. You can’t hold people’s emotional attention in that way for long.

If an ‘answer’ is supplied by revealing a solution, the campaign can progress because we get angry. It’s no longer a tragedy but an avoidable problem: ‘it doesn’t have to be like this’. In journalistic terms you have the elements of a scandal (Chapter 8).

Alignment gets everyone looking in the same direction, agreeing what the problem is, who suffers, who’s to blame and what the solution is. Skip any of this part and the audience won’t see what you are doing as relevant to them.

An unaligned au...