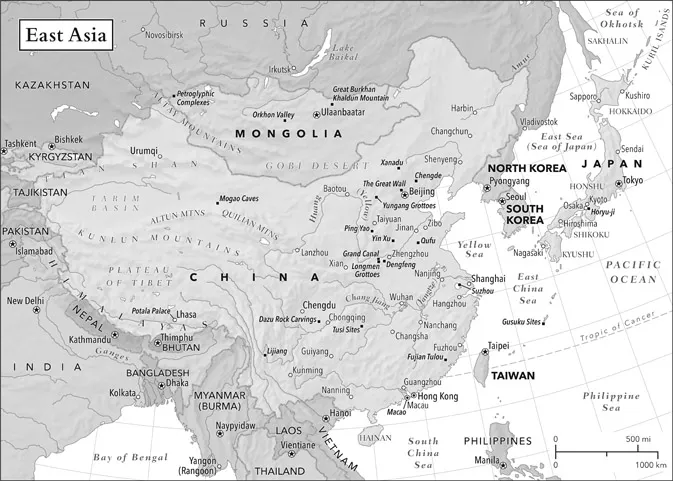

Japan, The People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, South and North Korea, Mongolia

The far eastern portion of continental Asia that includes the modern nations of China, Mongolia, Japan, Taiwan and the Koreas, is as highly varied as it is vast, encompassing a range of geographic features ranging from the high desert plateaus of China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region to the tropical forests of southern Taiwan. Primarily a temperate zone, much of East Asia is climatically well suited to wet rice cultivation, the practice of which has functioned as an engine for the architectural and engineering innovation for which the region has been known for millennia. Due to its position at the edge of the Eurasian Plate, the region is highly susceptible to seismic and volcanic activity, particularly along its coastal and island portions. This geologic reality, along with the region’s large forested areas, has contributed in part to a long tradition of building with wood.

Mainland China developed in relation to its principal river systems, the Yellow (Huang He) and Yangtze, both of which originate in the Tibetan plateau and together drain most of modern China, west to east. The generally parallel path of these rivers created a need for one of the world’s great engineering feats, the 2,000 kilometer-long (1,200 mile) Grand Canal, which was completed in the seventh century under the Sui Dynasty.1 The natural defenses of the Japanese archipelago, Korean peninsula and Taiwan afforded each protection from some of the forces of change that affected the mainland. In contrast, China was relatively vulnerable, in particular to the invasions of Chinggis Khan during the thirteenth century (which originated in Mongolia) and their antecedents. This fluidity famously gave birth to China’s Great Wall, but also to the cultural and economic connections that came about due to the two thousand year legacy of the great Asian trade routes. These geographic factors tended to give Japan and Korea a heightened level of control over their relationship with the outside world, and by the nineteenth century both were fiercely resistant to the overtures of the West in particular. Furthermore, Japan’s relationship with the rest of Asia during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is partly attributable to its own relative scarcity of natural resources, which fed its imperial ambitions that began with the nearby resource-rich Korean peninsula.2

The present-day nations of East Asia share a cultural cohesion based on common origins that scholars trace back to the third century BCE, under the Xianyang-based Qin Dynasty. Comparable to the cultural commonalities shared by today’s Western European countries, the products of this relationship remain in the Chinese writing system, Confucianism and branches of Buddhism, along with traditional systems of government.3 Today, East Asia constitutes one of the most populous and economically vigorous regions on Earth, with more than 20 percent of the world’s people and three of the four largest Asian economies.4 The cities of East Asia are among the largest and most architecturally distinguished anywhere, and its landscapes bear the imprint of the region’s centuries of planning and engineering accomplishments.

East Asia is one of the most active areas for architectural conservation practice in the world, largely by virtue of the post-war contributions of Japanese organizations and institutions, but increasingly due to contributions from China and the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea). Each country in the region supports an ICOMOS national committee, and each has successfully nominated multiple sites to the World Heritage List. China has the second-highest number of World Heritage Sites of any nation (behind Italy); even the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPR or North Korea), which typically does not participate in international institutions, has two sites on the List.5 In many ways East Asia’s position in the field represents an astonishing turn of events given the tumult of the twentieth century, which negatively impacted the architectural heritage of each nation in the region through wartime destruction, large-scale ideological revolution, or both.

Despite residual antipathy from the Chinese Communist Revolution, the Japanese imperial period and World War II, strong cultural and artistic ties among the East Asian countries that have existed for thousands of years remain strong to this day, largely to the benefit of architectural conservation efforts. With Japan’s role as a global leader in the field, China’s increasing level of activity both domestically and internationally, a robust system of cultural heritage management in place in the ROK, and a strong regional economy, East Asia is an important focal point for heritage management practice. After a period of violent hostility toward its traditional institutions and their buildings in the 1930s, Mongolia has since begun to embrace its unique cultural landscapes, nomadic heritage and monastery complexes. Taiwan (also known as the Republic of China) remains outside the UNESCO family due to ongoing disagreements with the People’s Republic of China, but nevertheless maintains a national conservation infrastructure, and a system for identifying and protecting heritage sites on the island nation.6 Though the DPR Korea remains obscured behind a repressive and insular regime, recent moves by UNESCO to recognize its cultural heritage indicate progress towards greater visibility into one of the world’s most opaque countries.

The great Asian trade routes contributed to the introduction of Buddhism to China from India, and with it came new architectural forms that resulted in hybridized building types, such as the characteristic East Asian pagoda – a blend of a traditional Chinese tower (que) and a Buddhist stupa.7 Numerous great cities developed on the basis of these ideas, such as Xi’an and Beijing, the latter of which was hailed in the mid-twentieth century as “possibly the greatest single work of man on the face of the earth.”8 The ancient Japanese imperial capital of Nara is home to some of the world’s oldest surviving wood buildings, many of which have been restored using techniques developed over the centuries that involve selective replacement of wooden architectural members to perform repairs or maintenance.9 European entrepôts established as early as the sixteenth century flourished in particular during the nineteenth century, resulting in today’s global cities of Shanghai, Hong Kong and Guangzhou (formerly Canton). Numerous ingenious architectural forms have emerged from the region over the centuries, ranging from the uniquely solid defensive domestic complexes of the Tulou circular communal houses of southeast China’s Fujian province, to the highly mobile gers (tents, or yurts) of Mongolia.

As is the case elsewhere on the continent, many long-standing traditions in the conservation of these distinctive forms of East Asian architecture are tied to religious beliefs, including respect for traditional building practices, philosophies and relationships between the human, spiritual, natural and built worlds. The Chinese concept of feng shui entails the importance of harmony between the built and natural worlds, and includes the long-standing use of color as a signifier of function. Another East Asian concept related to the traditional care of buildings and objects is the Japanese of wabi-sabi, which roughly translates to an appreciation for the flawed and impermanent. These two examples point to the deeply ingrained approach to management of the built world in East Asia, and the presence of a particular approach to conservation practice that emerged on the international scene during the second half of the twentieth century.

The East Asian notion of authenticity as a fluid, multi-dimensional concept relies on an emphasis on craft, design, and spiritual and cosmological traditions over original material. This perspective is partially based on the influence of Buddhism and Confucianism, but is also tied to the practical limitations of the region’s principal building material – wood – along with respect for traditional use and craftsmanship. Among the most famous manifestations of this attitude occurs at the Ise Grand Shrine in Japan every twenty years, whereby several structures on the site are ritually deconstructed and reconstructed on an adjacent site, a practice that dates from 1,400 years ago. Another illustrative case is the Confucius Temple Complex at Qufu in Shandong Province in northeast China, which has been restored no fewer than thirty-seven times by subsequent regimes, due to its significance as a link to Confucius himself, along with his final resting place. Numerous smaller scale restorations and reconstructions occur regularly as part of the maintenance regimes for wooden buildings throughout the region.

Despite an exceptionally tumultuous twentieth century, the conservation legacy of East Asia runs long and deep, with many individual buildings, districts, cities and cultural practices maintained over the centuries. East Asia was not subject to the kind of widespread, direct Western colonization as occurred in South and most of Southeast Asia, therefore conservation measures and organizations were largely developed within their local context, rather than imported by Europeans. The region was not, however, wholly immune from the disruptive activities of Western interests, which manifest in the form of large-scale removal of moveable cultural heritage in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries from China in particular. The punitive destruction of the Qing Dynasty Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace) outside Beijing by British and French troops in 1860 stands out as a particularly egregious act that in part informed the Chinese approach to heritage protection in the twentieth century. Reaction against foreign attempts to assert themselves in the region during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries led to prevailing attitudes and defensive positioning relative to cultural heritage in China, Japan and on the Korean peninsula.

The countries and kingdoms of East Asia have a tradition of issuing legislation and decrees that presage modern movements toward architectural conservation. The Meiji Restoration era of Japan (1868–1912) witnessed some of the earliest modern legislation for heritage conservation, adopted in 1871 (Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts), which was followed by other legislative efforts to the end of the nineteenth century. Legislation that focused on the conservation of districts also emerged from Japan, such as the Law for Special Measures for the Preservation of Historic Atmosphere (Ambience) in Ancient Capitals (or, the Ancient Capitals Preservation Law of 1966). A strong network of grassroots organizations in Japan supported post-war conservation movements in the country, such as the Zenkoku Machinami Hozon Renmei (Association for Township Preservation, 1974) complemented by robust training opportunities for professional conservators – such as a multi-year certification course – keeps the field active within the country’s shorelines.

The East Asian position on conservation is also informed by loss. For instance, on the Korean peninsula, the widespread loss of traditional homes, palaces and government complexes is attributed to the period of Japanese occupation (1910–1945), the Korean War (1950–1953) and the post-war development programs of the latter twentieth century. For all the devastation wrought by Imperial Japan upon other countries during World War II, the loss brought upon its own cities, towns and populace due to aerial bombardments during the war are immeasurable. In China, the new communist regime’s hostility to conservation was signaled after 1949 by a shift from architect and scholar Liang Sicheng’s vision of “preserving or restoring to the original condition” in the late 1940s to the new ruling party’s approach of “constructing the new, demolishing the old” by the 1950s.10 Liang’s proposal, known as the Alternative Plan, to place all new development outside of Beijing’s historic core stands out as one of the twentieth century’s great missed opportunities for urban conservation plan...