![]()

Chapter 1

The Dynamics of Sub-National Authoritarianism: Russia in Comparative Perspective

Vladimir Gel’man1

Sub-National Authoritarianism: A Framework for Analysis

Alderman Keane arrived 11 minutes late for a meeting of the council committee on traffic and public safety, of which he is chairman. The committee had a sizeable agenda, 286 items in all to consider. Ald. Keane took up the first item. For the record, he dictated to the committee secretary that Ald. A moved and Ald. B seconded its approval, and then, without calling for a vote, he declared the motion passed. Neither mover nor seconder had opened his mouth. He followed the same procedure on six more proposals, again without a word from the aldermen whose names appeared in the record. Then he put 107 items into one bundle for passage, and 172 more into another for rejection, again without a voice other than his own having been heard. Having disposed of this mountain of details in exactly ten minutes Ald. Keane walked out. The aldermen he had quoted so freely, without either their concurrence or their protest, sat around looking stupid. Most likely they are.

This newspaper report about the meeting of a session of a city council could be addressed to many of the local councils in present day Russia. However, it was published on 13 April 1995 in the Chicago Tribune (Banfield, Wilson 1966: 105). At that time, Chicago was a classical example of machine politics. The city was under the tutelage of Mayor Richard Daley, who for over two decades had exercised strict control over the key issues of politics and government. Daley’s ‘political machine’ not only enhanced his personal rule in the city, but also his influence at the state and national levels. Even though the case of Chicago may be considered to be an exception to the rule in US urban politics (Erie 1988): local-based ‘political machines’, controlled by local bosses, had for many years been able to impose their will on the politics of numerous large cities, whilst federal political actors and institutions had a rather limited impact (Banfield, Wilson 1966).

This constellation of the localisation of politics and the monopolisation of control over local elites may be termed ‘sub-national authoritarianism’ (Gibson 2005). In certain historical periods it was a feature of local and regional government in many states and nations, ranging from Latin America (Gibson 2005, Stokes 2005) to South-East Asia (Scott 1972) and Southern Italy (Chubb 1982). ‘Political machines’ in the United States were just one of many examples of sub-national authoritarianism (hereafter – SNA). However, the systems of SNA in various countries and regions varied substantively in terms of their genesis, patterns of government, and political outcomes. Whilst some SNA regimes disappeared others gradually became institutionally embedded. In this respect, SNA in any given country (including Russia) is not a unique and context-bounded phenomenon but rather a by-product of state building and regime change. A number of scholars have drawn many parallels between regional and local government in Russia in the 1990s and 2000s with ‘machine politics’ in other countries (Brie 2004, Lankina 2004). By placing the dynamics of SNA in Russia in a cross-national and cross-temporal comparative perspective we may gain new insights into the patterns of SNA in Russia and its development more generally.

The rapid and dramatic diversification of political developments in Russia’s regions and cities in the 1990s was widely perceived as one of the unintended consequences of the collapse of the Communist rule and of the Soviet state, which led to the spontaneous decentralisation of government. The degree of diversity of these political developments at times was similar to cross-national differences rather than to within-state differences (Gel’man, Ryzhenkov, Brie 2003). Most observers have pointed out two major trends in Russian regional and local politics in the 1990s: (1) the localisation of politics, where local-based rather than nationwide elites served as veto players in terms of their influence on mass behaviour, economic governance and property rights (Afanas’ev 2000, Brie 2004, Pappe 2000, Robertson 2007), and (2) the monopolisation of control over key resources in many regions and cities – mainly, in the hands of chief executives. It is not surprising therefore, that the emergence of ‘regional authoritarianism’ in Russia has been severely criticised for providing major obstacles to the development of democratic and market institutions (Golosov 2004, Stoner-Weiss 2006). In the 2000s, the localisation of Russian politics was undermined by the recentralisation of the Russian state (Gel’man 2009) and the en masse encroachment of nationwide companies on local markets (Zubarevich 2002). At the same time, local monopolistic controls over resources in the regions and cities had been transformed into a nation-wide monopoly, governed by the Kremlin, especially after (1) the abolition of the popular elections of regional chief executives (and of city mayors in many cities) and (2) the transformation of United Russia (UR) into the dominant party (Hale 2006, Gel’man 2008, Golosov 2008). The politics of the recentralisation of the Russian state only partially modified the sub-national authoritarian regimes – their autonomy from the federal government has been weakened and their diversity became less visible in comparison with the 1990s, but major patterns of regional and local politics have been sustained over time.

This chapter is devoted to the analysis of sub-national authoritarianism in post-Communist Russia from a comparative and historical perspective. Firstly, I will offer an overview of the dynamics of SNA and its typology, based upon the experiences of the ‘political machines’ in US cities from the 1870s to the 1930s, and Southern Italy from the 1950s to the 1980s. Then, I will reconsider the nature of SNA in contemporary Russia in the light of its development in other countries. I conclude by discussing the prospects for continuity and change to sub-national authoritarianism in Russia, and those factors which may bring about its transformation.

The Rise and Decline of Sub-National Authoritarianism

The development of sub-national authoritarianism is usually considered to be one of the stages in the process of state-building and institution-building in modern societies, or as a ‘halfway house’ in the path to political modernisation that arises from the spread of universal suffrage and competitive elections (Scott 1969: 1143). Local elites and political leaders, who acquired autonomy from the central government either before the introduction of competitive elections or due to these processes, had to invest significant organisational efforts into holding on to power and maintaining political control under conditions of electoral competition. First, they had to eliminate the threats of local challengers; second, they attempted to avert political risks initiated by nation-wide political actors. In other words, local elites were forced to establish mechanisms to keep themselves in power, regardless of their electoral support and the preferences of the voters, and they also had to act to prevent ‘hostile takeovers’ from nation-wide political actors. Their strategies included: the establishment of 1) a monopolist control over politics and government at the sub-national level through the use of local-based electoral ‘political machines’, and 2) effective ‘boundary control’ (Gibson 2005), which prevents the undermining of this monopoly ‘from above’ (i.e., by nation-wide political actors).

Historically, the term ‘machine politics’ was used to describe politic and governance in US cities. From the time of the Civil War until the New Deal, all large American cities were governed through the mechanism of ‘machine politics’ (Banfield, Wilson 1966: 116). ‘Political machines’ are defined as business organisations, which were established by local powerful groups for a special kind of business (power holding through competitive elections) in order to retain control over politics and government and mass political behaviour through the use of specific material and non-material incentives (Ibid.: 115, Scott 1969: 1144, Erie 1988: 26). Although ‘political machines’ at that time partially compensated for some of the other defects in the American political and social order, such practices led to the development of corruption and inefficiency in urban governments. Most observers agree, that the demise of ‘political machines’ in the United States over the period 1920-1930 was a natural consequence of the consolidation of the American state, economic growth and social progress, and their ‘life cycle’ (i.e., emergence, bloom, and decline) was merely a by-product of political modernisation and development (Scott 1969: 1146).

The ‘developmentalist’ model of ‘machine politics’, offered by James Scott, has certain limits for the comparative study of sub-national authoritarianism. It was not only in Third World countries, that SNA regimes failed to achieve their goals and often collapsed due to state failure, economic backwardness, ethic conflicts, etc. The factors determining the survival of successful ‘political machines’ varied widely in different sub-national settings, sometimes irrespective of the national political context. For example, Edward Gibson analysed the case of the SNA regime in the Argentine province of Santiago del Estero, where the governor retained political control over the region for more than half a century (from 1949 until 2004), despite the fact that Argentina experienced dramatic changes of governance and both democratic and authoritarian regimes were instigated during this period (Gibson 2005).

Whilst Scott has provided an analysis of the structural factors pertaining to the rise and decline of ‘machine politics’, Gibson focuses on the strategies of political actors who either seek to preserve or undermine SNA regimes. He argued that successful SNA regimes can achieve their goals if they are able to pursue three major strategies simultaneously: (1) the establishment of monopolist patrimonial rule (the parochialisation of power) at the sub-national level; (2) the nationalisation of the influence of sub-national leaders on nation-wide politics and government; (3) the monopolisation of national-sub-national linkages between respective areas and the country as a whole, in major political and policy areas (Ibid.: 109). From this perspective, nation-wide political actors during the process of democratisation may use two different strategies to undermine SNA: (1) employment of the apparatus of the central state (including law enforcement agencies) as a tool of coercive dismantling of SNA (as happened in the 2000s in Argentina), and (2) the spread of party competition from the national to the sub-national levels (as happened in the 2000s in Mexico). One should note, though, that political parties, especially if they collude with the state apparatus, may serve as instruments to preserve SNA regimes. Several examples include the emergence of PRI dominance in Mexico in the 1930s (Cornelius 1973), which enhanced the power of local ‘caciques’ (Kern 1973), the long-term one-party rule in the American South (Key 1949) and in Southern Italy (Chubb 1982), and regional political regimes in the Soviet Union (Hough 1969, Rutland 1993). Despite the significant differences between these SNA regimes as such, and their national political contexts, they successfully implemented the above-mentioned strategies of self maintenance, and achieved their political goals.

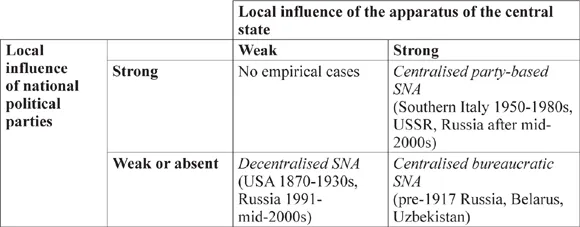

In this respect, both the centralised state apparatus (hereafter – the Centre) and nation-wide political parties should be regarded as exogenous factors of SNA regimes, which define their institutional environment. The constellation of influence of these two factors at the sub-national level in various countries can lead to the formation of a 2x2 matrix of various types of SNA regimes, which are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 A typology of sub-national authoritarianism (SNA)

Although the constellation of a strong presence of nation-wide political parties and the weak influence of the Centre at the local level is almost unimaginable, all other varieties of SNA have existed in different states and nations in different phases of their history. First, in many centralised authoritarian states and regimes, political parties could not exist at all or played only a rather modest role, especially at the sub-national level. Pre-1917 Russia is a model case: its provinces and cities were governed in a purely top-down manner by a bureaucratic hierarchy. Despite the limited autonomy of local government, political parties were legalised only after 1905 and remained weak in the provinces. Governors remained fully subordinated to the Centre and mediated centre-periphery relations, thus maintaining local SNA regimes as a logical continuity of nation-wide authoritarianism. In a similar vein, bureaucratic-authoritarian regimes in Latin American states (O’Donnell 1988) or in post-Communist Central Asian countries, such as Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (Luong 2002) maintained SNA regimes through the creation of bureaucratic hierarchies. Institutional settings of this kind of SNA were endorsed by the Centre’s coercive, and in some regimes, distributive capacities. The Centre tends to use its coercive capacity for administrative control over sub-national politics and government through bureaucratic appointments and dismissals, but centralised administrative control often co-exists alongside the relative autonomy of SNA regimes, which emerged as a by-product of the principal-agent relationships operating within the state bureaucracy. Deeply embedded patron-client ties cemented these SNA regimes which helped to maintain their continuity over time, often irrespective of political changes in national politics. An example of this is Argentina (Gibson 2005), where the re-emergence of competitive elections in the 1980s, after the collapse of the dictatorship, could not prevent the rise of a type of local politics which led to the ‘perverse accountability’ of citizens to their local ‘political machines’ (Stokes 2005). Thus, centralised bureaucratic sub-national authoritarianism may become self-enforcing. It may be undermined either by a comprehensive crisis of the state as a whole (as it happened in 1917 in Russia) or by the adoption of national level policies which have been deliberately designed to dismantle SNA regimes ‘from above’. The latter method, is especially salient in those cases where the pressure on SNA regimes ‘from below’ (by local political, economic, and social actors), is weak or absent (Gibson 2005).

‘Political machines’ which were present in American cities from the 1870s – 1920s represent another type of SNA. On the one hand, the American system of government at that time was heavily decentralised, and the coercive and distributive capacities of the federal authorities were rather limited (Skowronek 1982). Thus, state and urban governments held significant coercive and distributive capacities, which were successfully used by local ‘bosses’ for political mobilisation. On the other hand, the genesis of the United States party system ‘from below’ (i.e., at the state level) and trends of its early development (Shefter 1994) led to its decentralisation. Nation-wide party leaders could not maintain control over state and city party politics, and were dependent upon sub-national party leaders and local ‘bosses’, especially, in large cities. The weakness of administrative (the Centre) and political (party leadership) controls from nation-wide political actors gave a free hand to local ‘bosses’, who were able to establish SNA regimes and to successfully pursue all three of the above-mentioned strategies (local patrimonial rule, nationalisation of influence, and monopolisation of linkages) (Erie 1988). The formation of early capitalism during the ‘golden age’, accompanied by the rent-seeking efforts of ‘robber barons’, led to state capture at the sub-national level. The constellation of these political and economic arrangements also helped to maintain decentralised sub-national authoritarianism.

The decline and subsequent collapse of ‘political machines’ in American cities was the result of numerous factors (including an increase in the capacity of the federal government), which diminished the opportunities of local ‘bosses’ to control their fellow citizens (Banfield, Wilson 1966). One of the major attacks on ‘political machines’ came ‘from below’, at the sub-national level, as a result of the political activism of a rising urban middle class, and the emergence of the progressive movement, which became a major focus of local protests against SNA. In fact, the progressive movement in the early twentieth century played an important role in changing the political and institutional environment of US cities (Lineberry, Fowler 1967). After the New Deal, the reach of SNA was limited to Southern states (Key 1949) and some urban ‘political machines’, while the country as a whole successfully moved ‘from oligarchy to pluralism’ (Dahl 1961: 11).

Finally, Southern Italy in the 1950-1980s should be considered as a case of centralised party-based sub-national authoritarianism. The centralised Italian state coexisted with the centralised party system, whilst the economically backward South, was deeply embedded with patron-client ties (Putnam 1993), and the practice of ‘amoral familism’ (Banfield 1958) at the sub-national level informally supplemented hyper-centralisation. The dominant party, the Christian Democrats (CD), not only governed the country, but since the early 1950s established unchallenged control over the South, which served as its electoral base, and maintained a monopoly in local and (after 1970) regional councils (Chubb 1982). In fact, the CD, both nation-wide and sub-nationally, served as a large ‘distributional coalition’ (Olson 1965). The long-term state programme for the development of the Southern regions became a ‘cash cow’, which was used by the CD as a tool of monopolisation of national-sub-national linkages (Chubb 1981: 124). The distributive capacity at the sub-national level was concentrated in the hands of local party notables, who extracted major rents under the CD label. Organised crime, which collaborated with the CD, also supplemented the coercive capacity of the state. Parties other than CD (first of all, the Communist Party) had limited access to local political markets, and even their occasional electoral victories did not challenge the status-quo: widespread clientelism encouraged all parties to use similar political strategies (Chubb 1982).

The social base of SNA in Southern Italy included local businesses (which were dependent upon local authorities), the urban middle class (which was dependent upon public sector jobs), and the urban poor (Chubb 1981). Local CD notables successfully co-opted traditional patron-client ties into the lower echelon of the party hierarchy (Hopkin, Mastropaolo 2001) and used selective punishment of disloyal individuals and groups as the major negative incentive for loyalty. Unlike US ‘political machines’, which used positive incentives for loyalty, the Italian South demonstrated opposite trends; the use of side-payments by CD notables to their fellow citizens was rather limited (Chubb 1982, Warner 2001)...