1 Before We Even Get Started

Yes, the Federal Budget is Different from Yours and Mine, and it Faces Big Challenges

It’s good politics to talk about the federal budget as if it were an extension of the family: Mom and Pop sitting down at the kitchen table, sorting through their budget for the year. Once they have worked out the rent and utilities and such, they can approve how much to set aside for vacations and meals out, and begin spending right away. If they over-spend, or if they want a big ticket item like a new car, they can go out and get a loan. Under this (mis)perception, the president has a budget, too, which Congress “approves.” At some point—the pundits don’t tell us exactly when, but this book will—the federal government can begin spending money. If it spends more than it gets in taxes, it has to borrow to make up the difference. And because we don’t often plan as well as most American families do, we have gotten ourselves into a big fiscal hole, with the national debt getting out of control.

Of course, Washington doesn’t get excited over such trivial levels of spending as the average family, even though political leaders keep using the family budget analogy.1 They should know better; buying a car is not the same as buying an aircraft carrier. The differences start with the budget itself. Yes, the president has a budget, but this is nothing like the family version. Neither the timing, the content, the purpose, the inputs, the process or the execution are the same.

The president usually submits the budget on the first Monday in February. The budget covers the fiscal year that begins the following October, eight months away. It is a complex set of documents and tables—developed by departments and agencies and coordinated by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)—that take into account the president’s policies, the state of the economy, such urgent priorities as overseas military conflicts, and the costs of administering laws that Congress has previously passed. It reflects the president’s stance on the role of government in the nation’s affairs, be it a libertarian view that prefers a smaller government footprint, or a progressive one that favors greater government involvement. It is numbered by the year in which it ends; thus, the fiscal year that began October 1, 2016 is called Fiscal Year 2017.

Just because the president has come out with a budget doesn’t mean that the government can start spending that money right away. If some impatient bureaucrat bought even a box of paper clips with that “new money,” the law says he could go to jail. Instead, the president’s budget starts a months-long process on Capitol Hill aimed at passing twelve appropriations bills, plus related tax and other spending measures to bring the totals in line with Congress’s budget goals. During this February-through-September period, the government functions by spending money from bills passed in previous years.

For the most part, the money that Congress is supposed to appropriate by October 1 is for the year that begins that day. If Congress does not meet the October deadline, it must pass a temporary spending measure, called a continuing resolution, to keep the government going. Otherwise, the authority to spend money expires, and the government shuts down.

What Congress approves may or may not look like what the president has proposed, and there is always a tug of war between a president—who has the power to veto bills—and a Congress looking to assert its prerogatives over the nation’s purse strings. The Constitution, however, gives the spending power to Congress. It is laws passed by Congress that get the money flowing.

Running parallel to these annual appropriations is a big chunk of spending that is more or less automatic and funded by “permanent appropriations.” This includes Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment compensation—in other words, money that flows out, no questions asked, if the law entitles you to it. Congress controls how much money is in these programs by setting the eligibility standards, benefit amounts and other factors that determine how many people qualify and how much they get. Although this so-called mandatory spending—as opposed to the discretionary spending in those twelve appropriations bills—has been swallowing up bigger parts of the budget over the years, many of the programs behind it are quite popular. That, together with the fact that they are funded through “permanent” law rather than annual appropriations makes it quite difficult to trim then back. Note that “permanent” as used here has a different meaning from the popular understanding of the term. Congress can, and does, revisit and amend permanent law, with corresponding effects in the deficit.2

The budget covers not only spending, but also revenues. That includes more than just taxes. The federal government has hundreds of revenue sources, from personal income taxes to entry fees for national parks. An additional complication: Congress often uses deductions and other tax incentives to advance such policy goals as home ownership or energy conservation, goals that could just as easily be addressed by ordinary spending. These relatively hidden incentives, called “tax expenditures,” are harder to control than annual appropriations, yet they contribute to the deficit just as other spending does.

When a Tax Is Not a Tax

The two income streams just described—personal income taxes and entry fees to national parks—have important differences for budget purists. Personal income taxes are one of the many kinds of receipts that stem from the government’s sovereign power to tax its citizens. Citizens have no choice: Pay taxes or be penalized. These funds show up in the Treasury’s revenue accounts. Entry fees for national parks, on the other hand, stem from quasi-commercial transactions where the government, in the case of national parks, competes for your vacation dollars with places like Disney World and Six Flags. Here, citizens have a choice; they voluntarily hand over their money to the government in order to get something of value. These funds—loosely called user fees, as opposed to taxes—show up as offsets to spending and are placed in the outlay accounts of the budget. This puts them in a special category—“negative expenditures” is the technical term—even though they reduce the deficit just as taxes do. The idea behind this is to make the government’s revenue accounts reflect only what the government does as a sovereign power. Still confused? Read Chapter 9 (“Taxes and Tax Policy”), which explains it all, and more.

Just how much Americans should pay, how big the federal government should be, and what activities it should engage in or spin off, are inevitably front and center in any debate about the budget and go to the heart of what our democracy should look like. The themes of strong central government (with correspondingly higher federal taxes) versus more local control (with correspondingly lower ones) permeate U.S. history and show up in many of the analyses you will read in this book.

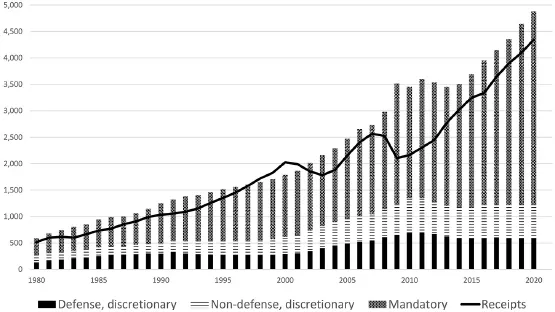

One of the biggest questions posed by the budget is how this country slipped from when it was running budget surpluses in the late 1990s to the present, where massive and long-term deficits are crimping our ability to cover expenses and grow the economy. A good place to start: ultimately, questions of how much to tax and how much to spend are decided in the political arena. The process reflects the compromises necessary to get a multi-trillion dollar budget package—taxes as well as spending—approved by a majority of the House and Senate plus the president. Each member has his or her own priorities, and the pressures of getting re-elected influence the process throughout. These pressures come from many sources, including constituents, the party leadership and outside groups. Additionally, such external events as terrorist threats/attacks, natural disasters and recessions demand emergency responses that bypass the spending controls written into law. Finally, the political pressures that support the biggest drivers of the long term budget deficit—Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security—are difficult to resist. The result: a tax base that does not support the demands being placed on it. Adding to the toxic mix these days is a partisan political environment that makes progress toward achieving budget balance especially challenging.

Figure 1.1 captures the challenge. Mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare currently take up about two-thirds of all federal outlays, and are growing; defense spending takes up half of the remaining, discretionary outlays. On the revenue side, federal receipts cover only 88 percent of federal outlays, leaving an entrenched deficit that is currently more than three-fourths of all defense spending.

Figure 1.1 Federal receipts vs. outlays, FY 1980–2020 (billions of dollars)

Source: Office of Management and Budget.

Any solution requires some compromise on items that have long been politically protected, like tax levels, national defense spending, income support programs, and even such routine tasks as maintaining national parks; for the problem these days is that the budget is not big enough to fund them all, and the will to compromise has not been enough to make much progress.

We cover the issues of how we slipped into chronic budget deficit, and how Congress and the president are dealing with it, in greater detail in Chapter 14.

What is in this Book

The federal budget covers the biggest pile of money around. The rules that govern the budget process are legion and convoluted, rules that Congress itself has developed to help get a handle on spending and revenues. This book splits this complex subject into four parts:

• Part I (Chapters 1–3), including this chapter, covers things you simply have to know before getting to the budget itself: the origins of the budget process, and how that process got to be the way it is. This part sets the stage for looking at budget technicalities and current budget issues.

• Part II (Chapters 4–6) introduces budget concepts that are central to the budget process and for understanding budget issues.

• Part III (Chapters 7–10) covers the tools that legislators use—appropriations, tax laws, credit and insurance programs—to advance the goals of budget policy. This part also walks the reader through a calendar year, pointing out the steps that occur each month of the process.

• Part IV (Chapters 11–14) takes on “big picture” issues that follow from the themes in earlier chapters: the budget and the economy, the budget and government performance, the budget’s effect on federal-state-local relations, and balancing the budget in a political environment.

Federal budget policy is as much about process as it is about money and programs. The process reflects laws passed by Congress that spell out in detail how the budget gets submitted, considered and administered. That the process is quite complex only adds to the problem of getting consensus in a city whose politics play out like an emotion-soaked tale of suspense. The aim of this book is to pull back the curtain on the laws and the suspense, so the reader can get a better grasp on budget policy developments across the spectrum of governmental responsibilities.

As you read this book, it is worth considering how a democratic nation of laws works its budget, from the taxes and other revenues it receives to the programs it funds. It starts with the lawmaking body, Congress, and reaches into every aspect of budgeting. It allows for constituent input, but ultimately depends upon the resolution of conflicting positions to enact the laws that keep things on track even as outside conditions change. This is what produced the major laws referred to in this book and which are listed in an appendix. When the process breaks down, as it has in recent years, or when the budget veers into structural imbalance, Congress must answer the question where things went off the track and develop the necessary solutions.

Questions for Chapter 1

1 What is the important difference between the way personal income taxes, on the one hand, and entry fees for national parks, on the other, are displayed in government accounts?

2 What fiscal year are we in right now?

3 Give an example of “mandatory spending.” What is the key characteristic of mandatory spending that distinguishes it from annual appropriations?

Discussion Items for Chapter 1

1 “[B]uying a car is not the same as buying an aircraft carrier.” Explain.

2 “Congress can, and does, revisit and amend permanent law, with corresponding effects in the deficit.” Give some recent examples of changes in “permanent” law.

Notes

1 See, e.g., Perry Chiaramonte, “Tea Party Group Casts National Debt as a Household Budget,” FoxNewsPolitics (September 27, 2011), www.foxnews.com/politics/2011/09/27/tea-party-group-casts-national-debt-as-household-budget.html; Senator Charles Grassley (IA), “Federal Spending” Congressional Record—Senate, vol. 159, no. 11, 113th Cong., 1st Sess. (January 28, 2013), p. S300; Representative Scott Garrett (NJ), “Concurrent Resolution on the Budget for Fiscal Year 2014,” Congressional Record—House of Representatives, vol. 159, no. 40, 113th Cong., 1st Sess. (March 19, 2013), p. H1599.

2 For more detail on manda...