![]()

1

Ancient Rights

Concern for rights, in the modern (subjective) sense at least, was not something one could have intelligibly expected of the ancients. No Homeric Greek would have thought to demand recognition of rights that he possessed as a human being. Neither would he have acknowledged any such rights in any other man.1 While it would be an anachronism to speak of the individual Greek's human rights, it is true, nevertheless, that our own notions of right have had their embryonic beginnings in the complex of evolving ideas that grew out of the social and political crises that characterized ancient Greece. The Greek philosophical idea of natural right, associated primarily with Plato and Aristotle, grew out of a conflict between ancestral right (Themis) in the Homeric clan and natural right (Dike) as it was established by the city (polis). Because all modern and contemporary notions of rights begin with a repudiation or radical revision of Platonic or Aristotelian natural right, modern and contemporary ideas of rights cannot be understood fully without first examining the nature and character of that to which they stand as the repudiations.

The problem can be put into perspective by reflecting on the subtleties involved in our own use of the term "right." The shift from a discussion of "right" to a discussion of "rights" involves more conceptually than a shift from a singular noun to its plural form. It is a shift from one concept to its opposite, from a notion of right expressed in terms of the moral authority of law (either ancestral or divine) over the interests of the individual, to a notion of right grounded upon the moral and/or ontological priority of the individual and his welfare. It is not a shift that could have occurred without historical preparation. The one notion of right does not imply the other. The concept of "rights" in the modem, subjective sense—the idea of rights that belong to a person independent of any moral virtue or natural merit, a liberty that belongs to him even against the interests of his country or his government—could not have arisen until human beings were perceived to exist as distinct beings in themselves, and not simply as reflections of their social and familial origins. That, it turns out, is a very abstract and elusive idea, especially for the ancients, both philosophic and pre-philosophic.2

It never occurred to the Homeric Greek that he might have rights due him as an individual person because it never occurred to him to think of himself as an individual independent of his origins, either ancestral, or (later) philosophical.3 His world was a world of mutual dependency. His very existence, derived from his place and performance in the household (oikos) (Politics I, 1252.a.24—1253.a.7)4

The Household (Oikos)

Prior to 1200 B.C., in Homeric Greece, the family served both as the locus of authority and the origin of all rights. The head of the Homeric household (the kyrios, or agathos, meaning "the good") through his function as the unifying head of the family, provided the members of his family with a guarantee of safety and protection. Fustel de Coulanges, in his classic study, The Ancient City, argued convincingly over a century ago that the authority of the agathos did not reside in his power but, rather, in the fact that "he is the priest, he is heir to the hearth, the continuator of the ancestors, the parent stock of the descendants, the depository of the mysterious rites of the worship and of the sacred formulas of prayer. The whole religion resides in him" (Coulanges, 116). The focus of Coulanges' remarks is the centrality of the Homeric domestic religion, the identification and worship of one's ancestors as one's own family's gods. The ancient family, he maintained, was more a religious association than a natural association. "Every family had its hearth and its ancestors. These gods could be adored only by this family, and protected it alone. They were its property" (Coulanges, 78, 52). The Homeric Greek's ancestors were the family's greatest benefactors; it was they who originally acquired and passed down the land and the whole protective body of the family to their heirs. Consequently, it is they to whom the family and its members had the greatest indebtedness. The living agathos, the father in the Homeric household, was, in effect, the first of all the existing members of this protective body: "The family and the worship are perpetuated through him; he represents ... the whole series of ancestors, and from him are to proceed the entire series of descendants. Upon him rests the domestic worship" (Coulanges, p, 112).

Family worship of ancestral gods was a self-unifying activity, both the cause and the effect of a shared identity. It was through the worship of, and loyalty to, their ancestors that family identity and loyalty were created and sustained, and from the strength and unity created by their shared, ancestral worship the family received its guarantees of safety, security, and whatever status it was to enjoy. The family functioned as a sacred shelter, protecting its members from the enmity of a hostile world, supported by the ordinances of the Gods themselves. The benefactions that the family's ancestor-gods bestowed on it were indirect. Their benefactions were little more than the civilizing consequences of their being worshipped, but no less the benefits for that.

Emphasis on blood-relationship and nobility of birth in establishing and recognizing rights preserved the strength and unity of the family and household, Blood relation created an unrenounceable unity stronger than friendship, more lasting than mutual advantage, and more reliable than good will. The Greek family could not be strengthened and unified so thoroughly without demanding exclusivity. To accept a stranger into the family would be, by definition, to loosen the bonds and to obscure what they made clear. A stranger, a person not of the family, could never be admitted to the family and its worship rituals. Strangers were outsiders; their presence before the ancestral gods would have defiled the homogeneity of the family.

People other than blood-related members of the family frequently lived in the household (oikos)—household slaves, concubines, illegitimate children, and others. However, they could not, strictly speaking, be considered members of the household. Their presence in the household would have served as a potential and likely source of disunity were there not some way to avoid compromising the demand that all the family's members be blood-related. The Athenian solution was to bring such people into the domestic worship through an initiation ceremony, something akin to marriage. The slave would be brought into the family religion, allowed to participate in its religious festivals and made a ceremonial part of the family. That slave would acquire the security of the family and the protection (therefore) of its ancestral gods. Entering the household worship also committed him to the family for life. As Coulanges writes, "... by the very act of acquiring this worship, and the right to pray, he lost his liberty. Religion was a chain that held him. He was bound to the family for his whole life and after his death.... As he was bound to it by his worship, he could not, without impiety, separate from it" (Coulanges, 151). The difference between the slave who was only a ceremonial member of the family and the blood-related members of the family remained obvious. Only blood-related relatives of the agathos were members in the fullest sense (MacDowell, 85), and their rights reflected that. They held the land. They formed a noble, land-owning aristocracy, the eupatridae.

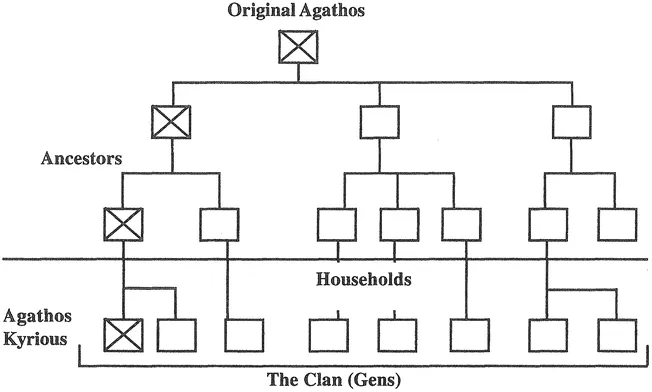

The Clan (Genos)

Households, the smallest units of the ancient Greek society, ordinarily found themselves part of larger clans or tribes. Debate has raged for decades over the relationship of the ancient household (oikos) and the ancient clan (genos). Was the clan a political association of many distinct and otherwise unrelated households? Or was it a protectorship, centered on an original, powerful household which acted as defender to other, weaker households and to clanless peoples, isolated from their families, who agreed to give their allegiance in return for its guarantees? Neither idea seems likely. Ancient literature gives ample evidence of the fact that the members of the clan believed that they all derived from a common ancestor. They worshipped common gods. They were also able to inherit from one another. This would all be outright impiety, a violation of the religion of the household, were it to occur amongst people not of the same family. It is much more likely that the clan (genos) was simply an extension of the family itself, the result of its success, endurance, and growth. Were a household, with its agathos as its ruler, so successful that it branched out over the generations and continued to grow in its economic and social power it would eventually become a clan or tribe (genos). Every member of a clan was a member of a Greek household, the blood-related offspring of an original agathos (Aristotle, Politics, I.ii. 5-6; Declareuil, 1970, 37; Lacey, 25). The members of the clan, ail united by the tie of birth, are said to have formed one "great family" (Coulanges, 151,141; Frisch, 38). It was crucial, of course, that the family remain united and strong if the clan were to be strong. That meant that the authority of the family, and hence the agathos, must remain supreme in the procreation, rearing and education of children. To this effect, Coulanges says, "in many Greek cities the law punished celibacy as a crime. This was in accordance with the ancient belief: man did not belong to himself; he belonged to the family. He was one member in a series, and the series must not stop with him. He was not born by chance; he had been introduced into life that he might continue a worship; he must not give up life till he is sure that this worship will be continued after him" (Coulanges, 64). The clan's authority over the individual was so great that its agathos could reject a child at birth were he to suspect his wife of infidelity or were the child itself deformed, and leave the child exposed to die or be sold into slavery.

No Greek possessed any rights whatsoever beyond the protective reaches of the clan and the household. Those who, through expulsion, the fortunes of war or some misadventure during travel, had been cut off from their clans were, strictly speaking, without rights. No idea of a pre-political or pre-tribal natural right, or universal, (subjective) human right belonging to every person as a subject, independent of his connections with the clan, was a part of ancient thinking. Rights were ail objective, not something one possessed so much as a right way of life in which one participated. If one had the use of the land, for example, it was only because it was (objectively) right that it be that way, and it was right because it had the sanction of one's ancestors, which is to say, it was the way of the tribe.

From the benefactions of the agathoi came all the rights the others enjoyed, In fact, the clan was considered to have a claim of sorts against the agathos arising from the recognition given him for his benefactions. The force driving the agathos to fulfill his debts to his people was the threat of disgrace that his failure would bring upon him (Adkins, 1960, 46). For the Homeric agathos and other members of the Homeric nobility, the measure of one's excellence was the degree to which he was able to avoid failure and disgrace. The rights of the Greek agathos were more akin to celebrations of a power and healthy authority that, when exercised, transmitted that power and health to his clan. The rights of the Homeric agathos were inseparable from the recognition given him by his people for the ancestral lineage he represented and for the unity and power which that ancestral lineage—through his own authority and leadership—conferred on the clan. Their united power was his power; the might of the clan, its skill in warfare, was at the same time his own might and skill. In honoring the might of their agathos and in deferring to his desires, the household and clan, in effect, united themselves and, in the process, received the benefactions of the power that they recognized in him. But, the power that they recognized in their agathos was as much a product of their own unifying act of recognition as it was a product of his physical or military prowess. Consequently, the Homeric agathos would have great love for his own people, since their power as a clan was a reflection of his own power no less than his own power was a reflection of theirs. What the members of the clan received was theirs not by (subjective) right, but, rather, only an occasion for the agathos to bestow his benefactions and thereby exhibit his own nobility (Nicomachean Ethics, IX, vii, 5; cf. Adkins 1960, 76).

Beyond the reach of his household or clan, no Greek felt the presence of his ancestral gods. The gods of his neighbors were hostile to him, and he to them. The deaths of those outside the clan offended no one.5 That is to say, to clans other than one's own one owed no duties. No morality required that one show concern for the welfare of those not related to him by blood. The actions of a Greek were not affected by the thought that he might be about to violate someone's natural or human right. War, plunder, and piracy were integral parts of Greek life.6 A captured city would be sacked and burned. The men would be killed. Women and children would either be held for ransom or enslaved. No rights would have been violated.7

Property Rights

The focal point for all these relations of authority in Homeric Greece was the land. The family and clan established its identity through the land on which they lived. It was on that land that the immovable tomb of their ancestors was located. Coulange tells us,

... a tie stronger than the will of man binds the land to him. Besides, this field where the tomb is situated, where the divine ancestors live, where the family is forever to perform its worship, is not simply the property of a man, but of a family. It is not the individual actually living who has established his right over this soil, it is the domestic god. The individual has it in trust only; it belongs to those who are dead, and to those who are yet to be born. It is a part of the body of this family, and cannot be separated from it.

(Coulanges, 91)

Property among the Greeks, then, was never considered to be the possession of any one person, but, rather, an ancestral trust. Property (land) could not be divided, even at the death of the kyrios. A divided inheritance would create smaller, weaker, more vulnerable clans. Consequently, property ownership always transferred to the oldest male descendent of the kyrios upon his death. If there were no male offspring on the father's side, property would transfer to the brother of the kyrios or to the children of his brothers and sisters, all descendants of a common ancestor and former kyria of the household. The rigor of the customs governing the transmission of property made it conspicuously clear that property was for all practical purposes inalienable, attached to the family or clan, and belonged to the individual only in his function as an the head of the household or clan (Wood, 18).

The rights one enjo...