![]()

part one

Introduction and Overview

![]()

one

Definition and History of Virtual Worlds for Education

Introduction

In the popular press, virtual worlds are almost always talked about in breathless tones of wonder and newness. They are described as the latest, emerging technology that has captured the hearts, minds, and funds of players young and old. The way you hear virtual worlds discussed, you would think that they appeared on the world stage just moments ago … a sudden miraculous arrival in their present high-definition, full-color, ultra-realistic glory. If virtual worlds were sold in cereal boxes, the labels would all shout “New!” “Improved!” or “Now even better!”

In reality, though, those boxes should read something like “New look, same great taste!” Virtual worlds have been around in some form or another for decades. If you include mechanical virtual worlds, we can trace their origins back even further. In this chapter, we will follow the winding trail of the evolution of virtual worlds over time. We will pay particular attention to the history of virtual worlds used for education. And we will look at some current and recent examples of virtual worlds designed especially for education. Before that, though, we need to define what we mean when we say “virtual world.” We need a working definition to provide a foundation for the rest of the book!

What’s a Virtual World?

What’s a virtual world? On first thought, this seems a pretty easy question to answer. A virtual world is a computer-based 3D world that you can explore by yourself or with other people. In a virtual world, you either explore as yourself (first-person) or are represented by a computer-based character called an avatar (third-person). This definition is a good starting point, but like most definitions, the more you think about the topic, the more complex the definition becomes.

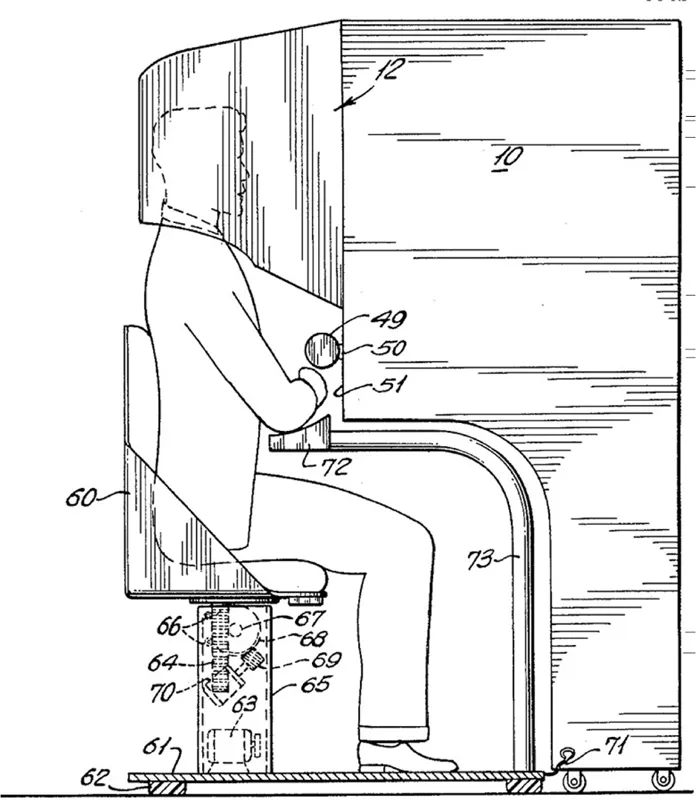

Let’s start expanding our definition by describing what virtual worlds are not, at least as we are going to talk about them in this book. In this book, virtual worlds are distinct from virtual reality. So what is virtual reality? Virtual reality consists of fully immersive 3D simulations. By fully immersive, we mean that the experience of the user in a virtual reality environment is a close functional simulation of reality, or a simulation of reality with some added “superpowers.” To achieve this, virtual reality-based simulations rely on a collection of software and related hardware. Virtual reality users wear head-mounted displays through which they view a simulated world or environment (Figure 1.1). These displays often include motion tracking. With motion tracking, as you turn your head from side to side or up and down, the simulated world tracks your head’s movement. So when you turn your head left or right, you see what is on either side of you in the virtual world displayed through the head-mounted display. Some head-mounted displays include headphones that similarly include motion tracking connected to audio. You hear the sounds of the virtual reality environment all around you, and the sounds move appropriately has you turn your head. For example, if you hear a dog barking off to your left and turn your head in the direction of the barking, you will both see the dog come into view in your head-mounted display, and hear the barking move from your left side to directly in front of you in virtual space.

FIGURE 1.1 Virtual reality hardware

Virtual reality simulations also frequently make use of data gloves. Users wear a glove (usually just one), and sensors in the glove track the movement of their hand through real space. This movement is then mapped onto the 3D space of the virtual world, and a cartoon-like image of the user’s hand appears in virtual space. With the glove, users can pick up, carry, and otherwise interact with objects inside the virtual reality world. For example, they can pick up and throw a virtual ball. Data gloves often include some form of force-feedback that allows users to “feel” the virtual objects that they interact with via the glove. A few very elaborate virtual reality setups even include what are essentially giant hamster balls that allow the users to walk or run in all directions, with elaborate motion tracking software mapping their movements into the head-mounted display.

Virtual reality is, in a word, cool! But it is not the topic of this book. We are focused instead on something just as cool: virtual worlds. What’s the difference? In this book, we define virtual worlds as computer-based environments that can be explored without the use of special hardware (other than a mouse or some other control device). Virtual worlds are explored by moving avatars through them or through first-person perspective. Virtual worlds can be single-player or multi-player. They can be graphical 2D or 3D worlds or text-based worlds. Virtual worlds can be simulations, but they don’t have to be. Virtual worlds can be games, but they don’t have to be.

Let’s unpack each of the components of this long definition.

Computer-based Environment

Right off the bat, we need to clarify. Virtual worlds don’t have to be computer-based. Depending on how you want to define them, you could say that virtual worlds have been around as long as humans. Human beings have always been very adept at creating virtual worlds in their minds based on stories they hear and books they read. Think of the last really good book you read. While reading it, you undoubtedly created your own very detailed virtual world based on the characters, setting, and storyline of the book. While deeply engrossed in reading, you probably stopped consciously noticing the words on the page at all. You achieved what game designers call a “flow state” in which the medium through which you encountered the virtual world of the story disappeared (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). You were fully engrossed in the world of the book: experiencing it firsthand. You, in short, became a designer, builder, and participant in a virtual world.

But for the purposes of this book, we are talking about interactive electronic worlds versus non-electronic virtual worlds, such as board games, dice-based games, etc. Further, we are going to focus on the design of computer-based virtual worlds. Virtual worlds have migrated to a multitude of platforms including game consoles (i.e., Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, Wii, etc.), portable game systems (Nintendo DS, Nintendo 3DS, PlayStation Portable, etc.), and—most prolifically—smartphones (iPhone, Android, Windows Phone, etc.). But most virtual worlds designed for educational use continue to be computer-based. Within a few years, this is probably going to change, but for now we’ll stick with the computer.

Exploring Virtual Worlds

In Chapters Two and Three, we will go into great detail about the mechanics of computer-based virtual worlds, looking at all aspects of how they work, how users can interact with them, and how the mechanics of virtual worlds can be used to your advantage to help people learn. For now, though, here is a brief explanation of what we mean by “exploring.” Virtual worlds are usually explored in two main ways: first-person and third-person (or avatarbased). Unlike virtual reality environments, exploring virtual worlds doesn’t require any special equipment beyond a computer, mobile device, phone, or gaming console.

In a first-person virtual world, you explore the world as if you are bodily embedded in it. You see the virtual world through your own eyes or, rather, through the eyes of the virtual you—your avatar. Avatars can be visible or invisible representations of the character that you play in the virtual world. In a first-person virtual world, your avatar might be a 20-feet-tall giant or a snake slithering along the ground, but you won’t actually see yourself: you’ll just see the world in front of your eyes. In commercial games, this form of exploration view is the standard in First-Person Shooter (FPS) games, called that for the obvious reasons that you see the virtual world from a first-person perspective, and because typically your main activity is shooting things. In an FPS game you might, and often do, see your arms represented in virtual space, frequently holding tools, guns, a chainsaw, and other objects with which to perform tasks and hunt down the bad guys. Usually, your legs are invisible in an FPS virtual world, although you are likely to hear your footsteps as you walk or run through the world.

In a third-person view of virtual-world exploration, you control a visible avatar and make it move through the world for you. Nearly all Massively Multi-player Online Role-playing Games (MMORPGs) use third-person, avatar-based controls. You spend most of the time in a third-person virtual world looking at the back of your avatar as it moves around. The only time you are likely to see your character’s face is when you first select the character at the beginning of the game, when your character dies, or during “cutscenes” (mini-movies designed to advance the storyline of the game).

Single-Player and Multi-Player Virtual Worlds

At the time we write this book, multi-player virtual worlds reign supreme both in the commercial realm and in educational virtual-world products. There is a good chance that you first became interested in the idea of using virtual worlds for teaching or training because of your exposure to and/or experiences with a multi-player game world. As we will explain in Chapter Four, there are a large number of learning benefits to be gained through well-designed multi-player virtual worlds. For example, many of the so-called “21st-century skills” we would like students to have when they enter the workplace are supported by the affordances and activities of multi-player virtual worlds: collaboration, teamwork, mentoring, competition, sharing, etc. Plus, multi-player virtual worlds are simply fun to inhabit, as a direct result of the same kinds of affordances that make them such good learning spaces.

With all the focus on multi-player virtual worlds, it is sometimes easy to forget that single-player virtual worlds offer an equally powerful set of learning benefits, including all the ones listed above. For example, like multiplayer virtual worlds, single-player worlds can support collaborative skill building, mentoring and teamwork. They just do it in a different way, as we will describe in Chapter Four. Also, single-player virtual worlds have been shown to be effective platforms for science, math, literacy, and health care instruction. They are particularly good at what is called epistemic gaming in which players role-play real-world jobs and related skills in the safe confines of a virtual world (Shaffer, 2006). Players in epistemic games might start out doing “lowly” jobs associated with some profession, and then take on increasingly complex tasks as their skills improve. In the commercial games world, single-player games set in virtual worlds are most often designed as either FPS in which your goal is to kill everything in sight or role-playing games (RPGs), that are very similar to educational epistemic games except that you are more likely to take on the role of an elf or ranger than of a scientist or city planner.

A (Very) Brief History of Educational Virtual Worlds

Now that we have a basic definition in place, let’s take a brief tour of the history of educational virtual worlds that fit our definition. As we’ve described, virtual worlds have been around in one form or another for decades. If we stick with our “electronic” qualifier, we still can look back to the mid-20th century to find the first virtual-world pioneers. Sensorama, a mechanical virtual world, was built in 1962 (Figure 1.2). It was designed as a kind of highly immersive personal movie viewer and featured 3D video, stereo sound, wind, and even smells (see www.mortonheilig.com/InventorVR.html).

FIGURE 1.2 Sensorama

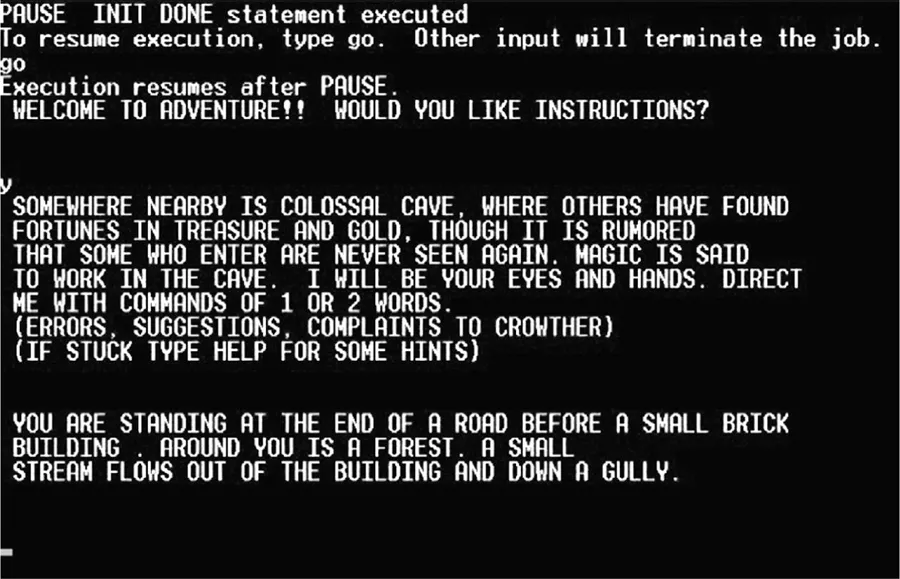

Narrowing our focus further to computer-based virtual worlds, we move a bit closer to the present day, but can still find early virtual-world examples starting in the 1970s. That is when the first computer-based text adventures appeared. These early computer games consisted of complex virtual worlds experienced entirely through the written word. Essentially these were very elaborate “choose your own adventure” books in electronic form. One of the first of these worlds, created in 1977, was called “Colossal Cave Adventure.” Colossal Cave Adventure enabled players to explore a virtual cave by typing in text commands. For example, if you wanted to move north, you would type “north” or “n” on the keyboard. Each time you moved to a new location in the virtual cave, you would be presented with a new description of your surroundings, possible exits, and tasks that could be performed at that location (see www.rickadams.org/adventure).

In the late 1970s, text-based virtual worlds went multi-player with the introduction of the first Multi-User Dungeons or MUDs. The first, actually called MUD (also called MUD1 and British Legends) (see www.british-legends.com), was developed in England and played via a telnet connection (this was pre-internet after all). Like Colossal Cave Adventures, players of MUD and its descendants could explore virtual worlds using written navigational commands. MUDs also allowed groups of players to communicate with each other via text chat messages. Early text-based MUDs and MOOs (Multi-User Dungeons, Object Oriented) included many design characteristics and features that would be quite familiar to modern virtual-world players and designers. For example, MUDs and MOOs usually featured narrative-driven interactive stories. They typically had fantasy, sci-fi, or mystery themes. Their gameplay centered on solo or group quests, usually involving battles against enemies. Often, they included the ability to take on more than one character type, to wield weapons of various kinds, and to manage inventories of tools and objects that could help with a quest. Although players couldn’t see their avatars, they could create elaborate descriptions of them, which could be read by other players.

FIGURE 1.3 Colossal Cave Adventure

MOOSE Crossing

One innovative MOO designed for educational use was called MOOSE Crossing. MOOSE Crossing was a text-based, multi-player educational world started by Amy Bruckman in the 1990s. Bruckman used MOOSE Crossing, with its embedded programming language called MOOSE, to teach computer programming to kids with mixed results that would foreshadow findings in many subsequent educational virtual worlds. Bruckman (2000) conducted a qualitative analysis of 50 children using MOOSE Crossing to study programming, finding that student learning of programming in the virtual world was extremely uneven: some kids learned programming in the virtual world, but many more did not. B...