1 What is ADHD, and what is not?

Key points

- For many researchers and clinicians, ADHD is an international disorder with a strong genetic and neurological basis. However, for critics it is a powerful label of social control and a symbol of the medicalisation of childhood.

- ADHD has received much attention in research and in the media, and there exists much debate about causation, over- and underdiagnosis, the medications used to treat this condition and the long-term outcomes for children and young people. Debate continues about the usefulness of diagnosis, the rigidity of the psychiatric classification systems used to diagnose psychosocial difficulties and what are perceived to be the negative effects of labelling and stigmatisation of children and young people.

- Although our understanding of ADHD is becoming increasingly sophisticated, the exact causal pathways of ADHD remain unknown. International research suggests that a biological, psychological and social factors combine to produce ADHD. Cultural variations exist in relation to the degree to which ADHD is considered problematic.

- Determining prevalence rates for ADHD is far from straightforward and depends on a multitude of factors. These include the social and political attitudes of the day, the availability of service provision, and cultural beliefs about the nature and management of childhood behaviour problems (Sayal 2008).

- There is currently not enough evidence to support the restriction of diet as a cause or treatment for ADHD and no evidence for the benefits of adding vitamins, herbal remedies or metals.

- The process of understanding ADHD is complex and relies on skilled and experienced nurses and other practitioners to evaluate the broad range of information and make sense of it within the context of the child’s individual development and wider family functioning.

What is ADHD?

A wide variety of terms are used to describe what will be referred to throughout this book as ADHD. This includes attention deficit disorder (ADD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and hyperkinetic disorder (HKD). The most widely used overarching term of ADHD refers to a neuro-developmental disorder characterised by a persistent pattern of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention that is more frequent and severe than is typically observed in individuals at a comparable level of development (American Psychiatric Association 1994). For the purposes of this book, ADHD is defined as a common behavioural disturbance of childhood, characterised by excessive hyperactivity, inattention and impulsiveness.

Whilst previously considered to be exclusively a disorder of childhood, it is now recognised that ADHD persists into adolescence, adulthood and older age. For children and young people to be diagnosed with ADHD, these symptoms should cause impairment in their psychological, social and educational development and functioning. For adults, impairment is also seen in their occupational and working lives. The degree to which young people are impaired varies, and depends on risk and resilience factors, the coexistence of other psychosocial difficulties and the support networks available to them.

Is ADHD new?

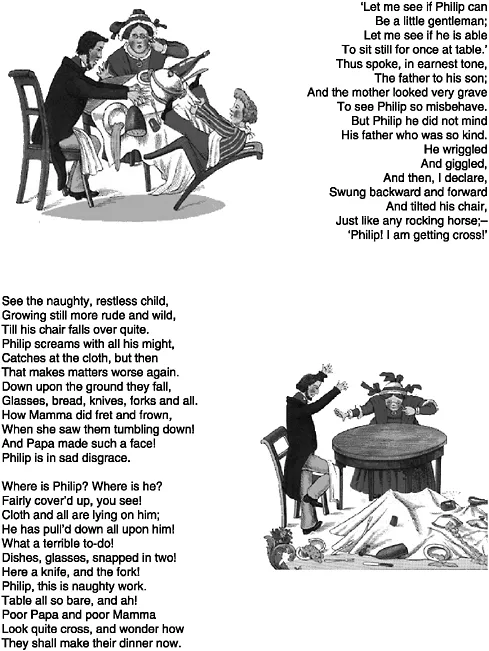

Contrary to popular belief, ADHD is not a new phenomenon. Reference to the hallmark features of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity has been made across the centuries (Dobson 2004). One of the first illustrations of ADHD was made in 1845 by Dr Heinrich Hoffman, a German physician and poet, who told the story of ‘Fidgety Philip’. He described a child whose behaviour might today be recognised as ADHD (see Figure 1.1 below).

At the turn of the 20th century, two British paediatricians, Sir George Frederic Still and Alfred Tredgold, wrote of a group of children who were described as defiant, emotional, lawless and disinhibited (Tredgold 1908; Still 1902). Believing that these children had a ‘morbid and abnormal defect of moral control’, these paediatricians suggested that the behaviours of the children were biological and constitutional rather than a product of poor parenting or child rearing. Their findings fuelled public controversy, clinical uncertainty and scientific debate (Biederman and Faraone 2005), and to a large extent this debate continues today.

Another landmark in the history of ADHD was the worldwide epidemic of encephalitis which occurred between 1917 and 1928. Many children survived this outbreak, but were left with impaired attention, hyperactivity, lack of coordination and poor impulse control (Wender 1995). Historical records note that many children who had suffered encephalitis were later diagnosed with ‘encephalitis lethargica’ or ‘post-encephalitic behaviour disorder’, the characteristics of which would today be referred to as ADHD (Adler and Chua 2002).

Figure 1.1 ‘Fidgety Philip’.

During the 1930s in Western Europe and the United States, the terms ‘minimal brain dysfunction’, ‘imbecility’ and ‘idiocy’ came into clinical use due to the similarities shown by patients with central nervous system (CNS) injuries arising from head injuries, infection and toxic damage (Rafalovich 2001; Schacher and Tannock 2002). Later in the 1950s the diagnostic label was changed to ‘hyperactive child syndrome’, or ‘poor impulse control’, reflecting that no underlying organic damage had been identified. In 1968 the term was once again modified to ‘hyperkinetic reaction of childhood’ and was included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (Spencer et al. 2007). The current definition of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) originates in the US and is in common use today. The ADHD debate continues all over the world, and is now much more informed by data from high-quality empirical studies of epidemiology, cause, pathophysiology and treatment than observational studies (Swanson 1998a; Barkley 2002).

How common is ADHD?

Determining prevalence rates for ADHD is far from straightforward and depends on a multitude of factors. These include the social and political attitudes of the day, the availability of service provision and cultural beliefs about the nature and management of childhood behaviour problems (Sayal 2008). As many problems of childhood and adolescence go unrecognised and untreated, prevalence estimates can only reliably be derived from epidemiological surveys. Several confounding factors make comparisons between existing prevalence reports difficult to make. First, rates vary depending on whether clinic, school or representative community samples are studied (Brown et al. 2001). Second, prevalence rates vary according to methodological differences, the assessment measures used and whether the ICD or DSM criteria are used. In North America and Australia, the DSM-IV is used and this primarily relates to the diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, whereas the ICD-10 is used in Europe and refers to a more stringent definition of hyperkinetic disorder, which is a narrower and smaller subgroup of ADHD (Fonagy et al. 2002). When DSM-IV criteria are used, point prevalence rates of 5–10% are reported (Fergusson et al. 1993), and where ICD-10 criteria are used a prevalence of 1–2% is reported (Swanson et al. 1998a). The assessment tools and classification systems used to identify and diagnose ADHD are discussed in detail in the following chapters.

ADHD: a worldwide phenomenon?

Regardless of which classification system is used, there seems to be little doubt that more and more children are being diagnosed and treated for ADHD. In the UK in the 1980s, one in 2000 children were diagnosed with ADHD. Today, the estimates are closer to six in 2000. Some have reported that referrals of children with ADHD are now overwhelming specialist child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in the UK (Salmon 2005). Rates of increase have been much steeper in the US, with 24 per 1000 children diagnosed in the 1980s, and estimates of 70 children per 1000 in the late 1990s (Olfson 2002). Various reports suggest that ADHD is the most common child mental health disorder in the US, and as many as half of all referrals to child and adolescent mental health services are related to this disorder (Barkley 1996; Greenhill 1998; Currie and Stabile 2006).

Despite the popular myth, there appears to be no evidence that ADHD is a by-product of American culture. It is not only in North America that rates of ADHD are reported to be high and rising. A review of studies from 50 countries across the world suggested that ADHD is at least as high in many non-US children as in US children (Faraone et al. 2003). In Australia, an increasing number of children with ADHD are being referred to child psychology and psychiatry clinics, with figures as high as 50% for some centres (Mellor et al. 1996) and rates of prescribing for stimulant medications mirror those in the US (Reid et al. 2002). Prevalence rates across European countries are significantly lower than those in North America (Anderson 1996; Timimi and Taylor 2004). However, an increase in the numbers of children being diagnosed with ADHD does not necessarily mean that the disorder is becoming more common. Rather, it may reflect differences in the definitions of ADHD, the diagnostic frameworks used, improved systems of identification and service delivery and changing attitudes towards disruptive behaviours of childhood and adolescence. Indeed, a large survey of the mental health of over 10,000 children in Great Britain found that there were no differences in the prevalence rates of hyperkinetic disorder in children aged 5–15 between 1999 and 2004 (Green et al. 2005). Similarly, a Scottish study compared children referred to a child guidance service and a group of control children matched for age, sex, socio-economic status and ability. All children were scored for hyperactivity using the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS) (Conners 1989). There were no significant differences in prevalence rates found as compared to US studies using the same measures (Gleeson and Parker 1989). This may suggest that apparent differences in prevalence of ADHD may be due to differences in diagnostic practice rather than true rates of the disorder itself.

Ethnicity and culture

There has been much research into the epidemiology of ADHD and treatments for ADHD, but little research into understanding the role of ethnicity (Gingerich et al. 1998). Despite this, ADHD has been variously referred to as a Western middle-class disorder of White boys (Olsfon et al. 2002). However, there are few high-quality research studies to qualify this rhetoric, and relatively little is known about how ADHD is experienced and manifested across ethnic groups. Across the world, there exists a range of perspectives held by parents, professionals and society about what constitutes socially acceptable and problematical behaviour (Weisz et al. 1991; Mann et al. 1992; Dwivedi and Banhatti 2005). Models of parenting, child rearing and behaviour management are each culturally bound and vary enormously across and within cultural groups. In addition, major differences exist in attitudes to help-seeking across ethnic groups (Eiraldi et al. 2006). Therefore, it is not surprising that there also exists significant variation in the way in which ADHD is recognised, understood and treated.

Much of the research about ADHD has come from North America and Europe, and it is only recently that the diagnosis has been investigated and recognised in different countries and cultures (Faraone et al. 2003). Several studies have illustrated widely differing rates of ADHD between countries and this may be partly due to the range of assessment processes and rating tools used, variations in the age range of children and young people in studies and differences in definitions of impairment which are also culturally determined. However, significant variations have been found even when the same rating tools have been used and these confounding factors have been controlled for. Mann et al. (1992) examined levels of hyperactivity in China, Indonesia, Japan and the US. They found that Chinese and Indonesian clinicians gave higher scores for hyperactive and disruptive behaviour than colleagues in the other countries (Mann et al. 1992). Dwivedi and Banhatti (2005) studied rates of ADHD in community samples and multi-site cohort studies as reported around the world. What seems evident from these reports is that it is very difficult to standardise views, attitudes and perspectives about ADHD and agree what constitutes acceptable or problematic behaviour (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2).

Does culture influence diagnosis?

The answer to this question is invariably yes, but how so is yet to be determined. Pastor and Rueben (2005) looked at parental reports of ADHD behaviours shown by children in the US to explore whether ethnicity played a role in diagnosis. Rates of the diagnosis of the disorder and use of prescription medication varied between White, Hispanic and African American children, and these differences could not be explained by racial and ethnic variables. Hispanic and African American children were less likely to be reported by parents to have ADHD symptoms and used less prescription medication compared to their White peers (Pastor and Reuben 2005). Similarly, Cuffe et al. (2005) used the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman 1997) as an additional measure to estimate rates of ADHD in a sample of over 10,000 children aged 4–17 years. They found that 4.19% of males and 1.77% of females reached criteria on SDQ rating for ADHD. Rate of ADHD reported in Hispanic boys was 3.06% and girls 0.95%; White boys was 4.33% and girls 1.98% and Black boys was 5.65% and girls 1.87%. The researchers presented their findings with caution since it is known that the SDQ can give false positive and negative results and does not reflect full DSM-IV criteria. Furthermore, their study did not include other ethnic groups such as American Indian and Asian groups. Therefore, Cuffe et al. (2005) concluded that further cross-cultural studies are needed to prove that there are true differences in the rates of diagnosis in ADHD across different racial and ethnic groups.

Table 1.1 Worldwide prevalence rates of ADHD

Table 1.2 Worldwide prevalence rates of ADHD

In a large meta-regression analysis of over 100 research studies carried out in 21 countries, Polanczyk et al. (2007) found that the highest reported rates of ADHD emerged from Africa and South America. Corroboration came from the use of a dimensional ADHD scale. Children from Japan scored lowest, Jamaican and Thai children scored highest and children from the US scored about average (Polanczyk et al. 2007). This seems to cast doubt over claims made by Timimi (2004) and other critics that the phenomenon of ADHD is almost exclusive to Western societies. It is important to consider that most of the information about the impact of ethnicity in the diagnosis of ADHD is from the US and is not readily transferable to the UK. This is because the ethnic population mix is different, and sociological factors such as insuranceled healthcare in the US must be taken into consideration. However, it is clear that the reporting of symptoms by parents in different ethnic, racial and cultural groups is widely variable. It is therefore possible that diagnostic rates could be very different to actual prevalence rates of ADHD, and further high-quality cros...