Information and information systems

What is information? Many people have attempted to provide definitions, but most of these are incomplete. A typical explanation is that information is processed data that has meanings for its users. But then questions arise in terms of what ‘meaning’ is. If information is to the study of information as object is to physics, and there are many laws by which we can study objects, then what are the laws by which we can study information? What is the study of information anyway?

What can be said here is that information is not a simple, primitive notion. Devlin (1991) compares the difficulties faced by a man in the Iron Age in answering the question ‘What is iron?’ and for a man in today’s Information Age when asked the question ‘What is information?’ To point the Iron Age man towards various artefacts made of iron would not be enough for him to answer the question ‘What is iron?’; similarly, demonstrating some of the properties of information is not enough to answer the question ‘What is information?’ People can feel the possession of information, and can create and use information. They gather it, store it, process it, transmit it, use it and even sell it and buy it. It seems our lives depend on it, yet it is so hard to tell what exactly it is.

In order to understand the nature of information, we may have to uncover some fundamental and primitive notions with which the question can be investigated and explained. The concept of a sign is one such primitive notion that serves our purposes here. All information is ‘carried’ by signs of one kind or another. Information-processing and communication in an organisation are realised by creating, passing and utilising signs. Therefore, understanding signs should contribute to our understanding of information and information systems (Stamper 1992).

What are information systems? One answer could be that computer systems can process and manage information. But, in recent years, it has become more likely that people will tell you that computer systems plus associated business processes, people (i.e. users) and the organisation are seen as information systems. From a slightly different angle, the study of information systems focuses on how to build information systems and how to make an organisation become an effective system in using information and managing the activities of such systems.

This study of, or inquiry into, information systems is an active area to which other research and industrial communities have paid much attention. There has been much discussion on its pluralistic and interdisciplinary nature, and its foundations. An increasing number of researchers and practitioners are defining information systems as social interaction systems. Social and organisational infrastructures, human activities and business processes are considered to be part of information systems. Information systems in this definition can produce messages, communicate, create information, and define and alter meanings.

The UK Academy for Information Systems provides the following definition of the domain of information systems (UKAIS 2014: 379): ‘the means by which people and organisations, utilising technologies, gather, process, store, use and disseminate information’. Ray Paul (2010) offers the following: ‘Information systems is information technology in use’. Many authors emphasise the importance of studying information systems in this postmodern society, as well as their interdisciplinary nature. For example, Avison and Nandhakumar (1995) suggest that information systems encompass a wide range of disciplinary areas such as information theory, semiotics, organisation theory and sociology, computer science, engineering and perhaps more.

Business informatics

Computer science, although not as old as physics or other sciences, is recognised as a fairly established scientific discipline. Information systems, software engineering and computer engineering are other disciplines that emerged afterwards and are recognised by the world’s largest educational and scientific computing society (Association for Computing Machinery [ACM] 2013).

The word ‘informatics’ came from the French word ‘informatique’. For many, informatics is more or less a synonym of computer science and its related disciplines recognised by ACM, with some reference to the human and organisational context. This places a great deal of emphasis on the methodologies, means, technologies and tools with which information is processed and managed. The definition of informatics from the Informatics Research Centre (IRC 2013; www.irc.reading.ac.uk) emphasises different aspects by stating that informatics is ‘the study of the creation, management and utilisation of information in scientific and economic activities’. Business informatics aims to relate informatics to a business context and to investigate how information resources can be effectively managed and utilised to add value to an organisation.

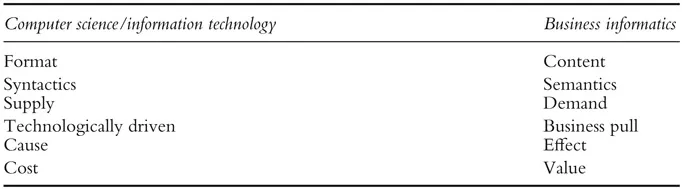

As an illustration, Table 1.1 summarises distinctive differences in the objectives of study between technical subjects such as computer science and information technology (IT) compared with business informatics. This table shows that the technically oriented subjects focus on the format and syntactics by which information is organised and represented, while business information is more concerned with getting the right information content and right semantics of information. The technical studies focus on the supply of technical means and are motivated by technological development, whereas the attention of business informatics is on addressing the demand that arises from business. IT and the like are drawn towards the causes of problems and consider how to invest in technology spending and how to make it cost-effective; conversely, business informatics centres on how to achieve an optimal effect of technology and maximise value. Both approaches are important, but perhaps the perspective of business informatics makes the focus of study more closely relevant to business motivations once the technologies have become available.

TABLE 1.1 Difference in study objectives

Issues and challenges in information systems

Information-processing and information services have become a major industry that plays a significant role in the current era of the digital economy. Even as early as in the 1970s, Porat (1977), based on an analysis of various sources, suggested that in developed countries such as the USA and Western European countries, approximately 50 per cent or even more of the labour force was engaged in information work. The International Labour Organization (ILO 2006) reports how the rise of IT has brought about a transformation of the workforce on a global scale.

Box 1.1 Techno-economic paradigms

The notion of the change of ‘techno-economic paradigms’ developed by Freeman (1991) and Perez (2009) is invaluable in understanding the link between the diffusion of ITs on the one hand, and growth and employment on the other. The change of ‘techno-economic paradigm’ approach incorporates and stresses both the direct and indirect effects of It.

The process of the innovation and diffusion of new ITs that took off in the 2000s constitutes a radical transformation in the means of production, distribution and exchange (Table 1.2). It has already profoundly affected international trade and investment, the movement of capital and labour, and many work processes and products. It has also accelerated the shift towards services and their outsourcing internationally. The rapid spread, ongoing development and pervasiveness of this flow of innovation is driving a massive reconfiguration of world production and distribution, as well as of the management systems of enterprises and public agencies – with major consequences for employment patterns (ILO 2006).

TABLE 1.2 Global developments in ICT, 2001–2013

| | 2001 | 2007 | 2010 | 2013 |

|

| Mobile phone subscription | 15% | 50% | 75% | 96.2% |

| Individual using the Internet | 8% | 20% | 30% | 38.8% |

| Fixed telephone subscription | 17% | 19% | 17% | 29.5% |

| Mobile-broadband subscription | 0% | 4% | 11% | 16.5% |

| Fixed broadband subscription | 1% | 5% | 8% | 9.8% |

Measuring the overall economic impact of ITs has, however, proved controversial. For many years, economists were troubled by the ‘Solow productivity paradox’, named after the economist who pointed out that computers were everywhere, but that no impact was visible in terms of productivity statistics (cited in Brynjolfsson 1993). Economic history suggests that major technological shifts take years to spread widely enough to clearly affect aggregate economic performance. The pace and reach of diffusion of ITs is unprecedented, but economies and societies are still at an early stage in learning how to make full use of their potential (ILO 2006). Numerous studies have reported large company budgets being set aside for IT and huge amounts being spent on systems development projects, yet with only a low economic return from the high investment.

Strassmann (1990, 2004) argues that there is no guarantee that large investment in IT will lead to high business performance or an increase in revenue: ‘no relationship between expenses for computers and business profitability’ (Straussman 1990) on any usual accounting basis across an industry. Some companies use IT well, but others balance this positive effect with poor returns on IT investment. Many surveys in industry exhibit evidence that a considerable number of information systems developed at great cost fail to satisfy users or have to be modified before they become acceptable. According to an analysis put forward by the US General Accounting Office in the late 1980s, among a group of US federal software projects totalling US$6.2 million, less than 2 per cent of software products were used as delivered and more than half (including those not delivered) were not used. The situation has not improved since.

A recent example is the failure of the computer system upgrade in the UK National Health Service (NHS). The National Programme for IT in the NHS was an ambitious £11.4 billion programme of investment designed to reform how the NHS in England used information to improve services and patient care (House of Commons 2011). The programme was launched in 2002 with the aim of creating a fully integrated electronic care records system, which was expected to cost around £7 billion in total. The original objective was to ensure that every NHS patient had an individual electronic care record that could be rapidly transmitted between different parts of the NHS in order to make accurate patient records available to NHS staff at all times. However, the programme was abandoned in 2011 with the cost having reached £10 billion. A report by the influential Public Accounts Committee concluded that the programme ended up becoming one of the ‘worst and most expensive contracting fiascos’ in public sector history (BBC 2013).

Similarly, in 1997, Advanced Technical Strategy Inc. published their study ‘The Software Development Crisis’ on the Internet, as quoted in Box 1.2 (Boustred 1997). In this figure, the ‘shameful numbers’ show that a majority of projects cost nearly twice their original budgets.

Box 1.2 Shameful numbers

- 31.1% of projects are cancelled before they are ever completed

- 52.7% of projects cost 189% of their original estimate

- 16.2% of software projects are completed on time and on budget

- In larger companies, only 9% of projects come in on time and on budget with approximately 42% of the originally proposed features and functions

- In small companies, 78.4% of software projects are deployed with at least 74.2% of their original features and functions

Bloch et al. (2012), in conjunction with Oxford University, published a study on a total of 5,400 large-scale IT projects (projects with an initial budget of greater than $15 million) and found that the well-known problems with IT project management are persisting. Some key findings are quoted below from the report:

- 17 per cent of large IT projects go so badly that they can threaten the very existence of the company.

- On average, large IT projects run 45 percent over budget and 7 percent over time, while delivering 56 percent less value than predicted.

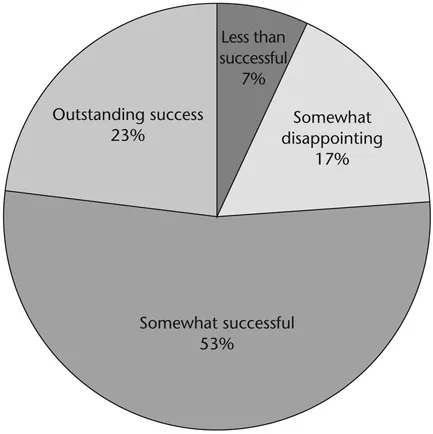

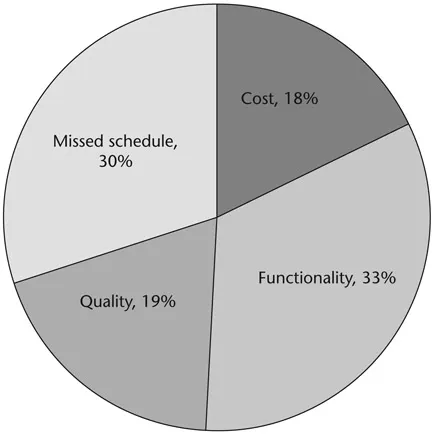

According to another report (Handler 2013), customer acceptance figures show that more than two-thirds of software products are never used or never completed. One of main reasons for these failures is inappropriate studies on users’ requirements that lead to incorrect systems analysis and design. Studies have been continued and similar outcomes have been reported, albeit with some slight improvements. Based on a recent report from Handler (2013), 24 per cent of IT projects are viewed as less successful or even worse (Figure 1.1). Figure 1.2 shows the reasons why IT projects fail. It suggests that the mismatch of functionality between what is required and what is delivered is the main reason for the failure of IT projects.

FIGURE 1.1 Customer perception of IT project success (Handler 2013)

FIGURE 1.2 Reasons for IT projects being less than successful (Handler 2013)

In determining the success of an IT project, the social, cultural and organisational aspects, as opposed to technology itself, play a decisive role. ‘A computer is worth only what it can fetch in an auction’, Franke (1987) wrote. ‘It has value only if surrounded by appropriate policy, strategy, methods for monitoring results, project control, talented and committed people, sound relationships and well-designed information systems.’ ...