eBook - ePub

Afghanistan

The Soviet Union's Last War

Mark Galeotti

This is a test

- 224 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Afghanistan

The Soviet Union's Last War

Mark Galeotti

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The Soviet Union's last war was played out against the backdrop of dramatic change within the USSR. This is the first book to study the impact of the war on Russian politics and society. Based on extensive use of Soviet official and unofficial sources, as well as work with Afghan veterans, it illustrates the way the war fed into a wide range of other processes, from the rise of grassroots political activism to the retreat from globalism in foreign policy.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Afghanistan è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Afghanistan di Mark Galeotti in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Historia e Historia militar y marítima. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1

Introduction: Invasion

War puts nations to the test. Just as mummies fall to pieces the moment that they are exposed to the air, so war pronounces its sentence of death on those social institutions that have become ossified.

Karl Marx

When Soviet troops seized the main centres of Afghanistan on Christmas Day, 1979, there were those who saw it as proof that after the years of détente, the USSR was once again on the offensive. Headlines spoke of 'the empire striking back', of 'red legions on the march'. At the same time, a relatively unknown Party administrator from the sleepy and prosperous region of Stavropol had just been brought onto the Politburo, albeit as a non-voting member. Eventually, after Mikhail Gorbachev had become the Party's General Secretary, his decision to withdraw his troops from this 'bleeding wound' was to leave one of the most striking series of visual images of his revolution, proof not only that the USSR was no irresistible military colossus, but that its goal, far from expansion, was simple survival. The regime that was left in Kabul managed to outlive Gorbachev's Soviet Union, but not by long, and as of writing, the same guns and rockets are being used in civil war, not only in Afghanistan but in former Soviet Moldova, Tajikistan and Georgia. The war seems not so much to have 'Sovietised' Afghanistan as 'Afghanised' the whole USSR.

Thus, for many, it looms large in explaining the downfall of the old order in Moscow. Many of its veterans, for example, find obscure satisfaction in the thought that the war that left them physically or mentally scarred, shunned or destitute, inflicted as painful a toll on the regime that sent them there in the first place. Others, especially in the Islamic southern republics, are keen to portray it as a purely imperial war, a chapter in the story of Russia's drive south in which its subject peoples finally came face to face with the truth about their despotic masters and began to resist the Muscovite yoke.

Certainly the war was important in its effect on the people and government of the old USSR and, indeed, its successor states. It touched more than the veterans. It touched every mother whose son served there or whose prayers or cash managed to prevent that fate. It touched every bereaved sweetheart, wife, father, son or daughter. It still touches everyone who has to live or work with the afgantsy, the veterans of this war, or care for them, or speak on their behalf. It is a powerful image in the developing debate of the USSR's and Russia's future in the world, and for many a damning indictment of its past.

Yet it did not destroy the Soviet Union. For this was a relatively minor, if ill-conceived and uncomfortable military adventure, eminently supportable, a negligible drain on the resources of the USSR. Its real importance is two-fold: as a myth and as a window. In the context of the collapse of the Soviet system, the war became used as a symbol for a variety of issues, from the cost of supporting such a huge and seemingly useless army to the arrogant foolishness of the old regime. Scattered, politically marginalised, ostracised, disempowered, the veterans and the other victims of the war could not make their views heard, and thus the mythological picture of the war, conjured from the prejudices, perceptions and political needs of a variety of journalists, politicians, academics and propagandists, came to dominate. For the outsider, though, the war also provides an extraordinarily rich source of insights into the Soviet Union of the 1980s and early 1990s and the new Russia which succeeded it. This book looks largely at central politics and Russia rather than the other republics. It will also perforce touch but lightly on the complex question of foreign policy. Yet above all, this analysis of the war is, inevitably, a case study of the political and social processes of the decaying late Soviet order, opening a window onto the forces at work. The war was by no means a critical factor and its realities became increasingly indistinguishable behind a thick patina of rumour, myth, sensationalism and wishful thinking, yet it did play a role in influencing a wide array of issues, from the spread of informal political movements through the shift away from conscription to the rise of Russian vice-president (and afganets) Aleksandr Rutskoi. Even for the military, for whom it had more direct importance, it was largely important in illustrating and emphasising other processes and pressures already at work, and the friendships and alliances formed in war could as easily be set next to or trumped by other affiliations based on ideology, comradeship or self-interest.

Thus my image is of a small war, a squalid and trivial expression of imperial arrogance, swept up into the whirlwind of politics of the dying years of the Soviet Union, used as a political tool and symbol by one élite group or another, until it was superseded by other, newer, better, bigger symbols. At this point it was largely discarded and those for whom it had real importance, the veterans, the war wounded, the bereaved, found themselves trying and largely failing to salvage something from the wreckage. By late 1992, a mere four years after the final Soviet withdrawal, the Afghan War has definitely become history, its victims stranded in its limbo.

Afghanistan in Crisis

If the revolution is put down, left progressive forces will sustain a crushing blow. If the revolution is successful, we will get a lasting headache.

Colonel General Akhromeev, at the time of the 1978

'April Revolution' in Afghanistan1

'April Revolution' in Afghanistan1

One of the shrewdest military minds of his generation, Akhromeev was quite right. As with so many 'people's' regimes, that of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan was established not by revolution, but by coup. This was, after all, hardly fertile soil for socialism. The educated, West European Karl Marx would no doubt be astonished and horrified to see what sort of groups and countries have since tried to wrap themselves vainly in the red banner of his ideology. For Afghanistan is an unruly country, with a tradition rich in war and unrest, a product of the perennial struggle between the centralising power of the kings and the cities, and the authority of the tribes, the villages and the local religious leaders, a struggle which the countryside usually won.

The ethnic character of the country is dominated by the division between the Pushtu-speaking Pathans of the south and east, who made up around 42 per cent of the population before 1979, and the Turkic and Iranian minorities of the north, which include Tajiks, Uzbeks and Turkmen. Traditionally the Pathans have dominated the country, and their natural ties are with their fellow Pathans in Pakistan, divided by the wholly arbitrary Durand Line, the border imposed by Britain in the last century, whereas the Turkic and Tajik peoples looked to their ethnic brothers to the north, in the Soviet Union. Yet Pathan, Tajik and Turkic peoples did share the Sunni form of Islam, and there are other groups, most notably the Hazaras of the central mountains and Farsiwans of the west, who are Shia Moslems, who ultimately accepted the spiritual writ of the imams of Iran.

The country is no less fragmented and hostile geographically. Afghanistan is largely a dry and rugged land, dominated by the high Hindu Kush mountains of the east and centre and by the plateaus and deserts of the west and south. In the mountains, a modern, mechanised army was limited to a handful of vulnerable, winding passes, and in the desert it was choked in dust and sand. The climate is one of extremes, and men and machines were stretched to their limits by cold, snowy mountain winters and dry, suffocating desert summers. Life is no less hard, with average life expectancy in the late 1970s of no more than 40, and only half of all children surviving beyond their fifth birthday. In such an environment, the local community had to develop and retain strong bonds to survive and such were the difficulties in maintaining communications in this land that these communities retained an independence and, indeed, exclusivity rarely matched in the modern world. Thus, the Soviets were to come to discover that the Afghans were not urbanised Westerners like the Czechs and the Hungarians, but a people still raw in warlike vigour, a people for whom blood feud and banditry were a way of life ('Have you an enemy?' goes the Afghan proverb, 'Yes, I do have a cousin.') and for whom civil war was as much a national sport as buzkashi, their distinctive form of polo, which tastefully substitutes a rotting sheep's carcass for the ball. A people, in short, with a will to continue the war that ultimately proved to be lacking in Moscow.

Various forms of monarchy and a rough-and-ready constitutional republic all failed to tackle the underlying problems of the weakness of central authority and were thus expressions of the politics of the handful of cities and proportionally minute urban elités. In 1979, of a total population of some 15 million, the capital held no more than 700,000 —and the total urban population was estimated at around 1,700,000. Prince Daoud had seized power in a coup in 1973 and founded a republic with himself as president, but he too found himself unable either to impose his will on the countryside or satisfy the demands of the educated city intellectuals, for social, political and economic modernisation. They wanted to see Afghanistan with a literate population, sexual equality, factories and all the other trappings of a modern state, and when Daoud failed to deliver, many began to turn against him.

One of the beneficiaries was the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), which began to build for itself a power base within the officer corps and civil service, and when Daoud began to round up their leaders in April 1978, they themselves seized power in an effective and truly 'Leninist' counter-strike. The coup left the country in the hands of Nur Mohammed Taraki, Chairman of the Revolutionary Council, and Hafizullah Amin, his Prime Minister. The coup caught the Soviet Union by complete surprise. After all, the PDPA had never been rated that highly and the orthodox line at the time had been more pragmatic than principled. Régimes such as Daoud's had been perfectly acceptable to Moscow so long as they could be of use. There was a need

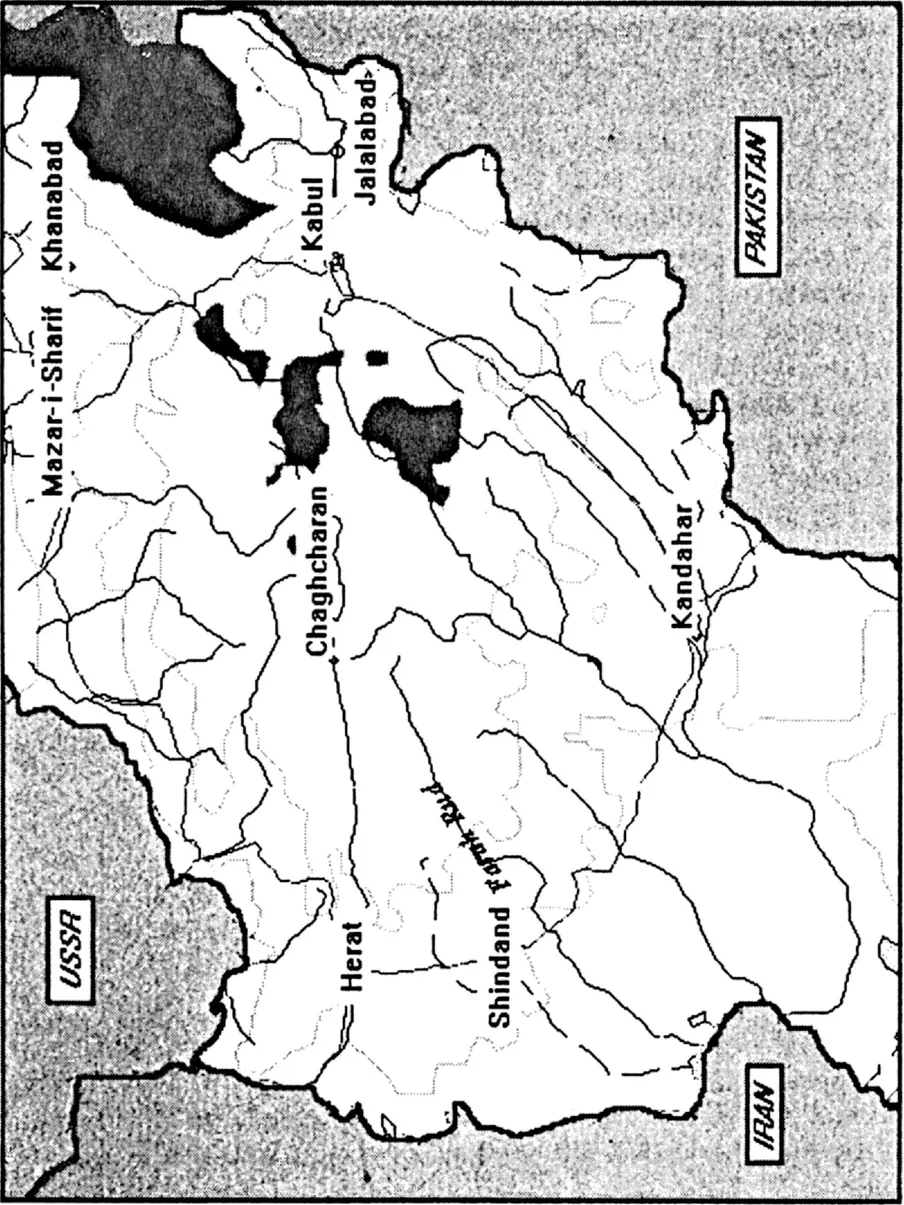

AFGHANISTAN

Outline map showing main towns and cities, roads, rivers and contours

for a quick policy decision on this new regime in a neighbouring and allied country.

Most political systems depend on the informal chat and the nod and a wink to some degree, but in the Soviet Union of the 1970s, the formal structures of power and bodies such as the Politburo (the Communist Party's 'cabinet') had become little more than rubber-stamps for the ad hoc gatherings of various grandees. In this case, the key group was built around the structure of the Politburo Commission on Afghanistan. Chaired by Foreign Minister Gromyko, this included as permanent members KGB Chair Andropov, Defence Minister Ustinov and possibly Chief of the General Staff Ogarkov and First Deputy Foreign Minister Kornienko; Mikhail Suslov (as Central Committee Secretary for Ideology and thus high priest of Brezhnevian orthodoxy) and Leonid Brezhnev himself were also privy to its deliberations. Following the 'April Revolution', the Commission met in an expanded session which also called in Boris Ponomarev, director of the Central Committee's International Department and his deputy, Rostislav Ulyanovskii as well as Arkhipov, who represented the Council of Ministers. Thus, ten men, representing the Party, the military, the KGB and the civil service could meet and effectively dictate Soviet foreign policy on the spot. The decision was taken to recognise the new regime. How could they do otherwise? The PDPA was an avowedly pro-Soviet socialist movement. By seizing power, it had shown itself to be more effective and with deeper military support than the previous regime. There seemed no viable alternative; and Moscow could hardly afford to repudiate the new masters of a country on its southern and conceivably vulnerable borders.

The decision may have seemed obvious, but in making it, the Soviets linked their fates with a regime lacking a real social base in this overwhelmingly rural, Islamic, even medieval nation. The urban intelligentsia of the PDPA launched a heavy-handed and insensitive programme, ranging from land redistribution to the education and emancipation of women, which violated religious laws, traditional customs and the very balance of power between the centre and the localities. Popular dissatisfaction mounted; by October 1978, this had become armed insurrection (in the Nuristan province), a classic product of what Fred Halliday called the 'malign marriage of exported Soviet bureaucratic and authoritarian political practices with ones already present in the political cultures and social structures of the countries concerned'.2 Moscow — especially in the shape of the Central Committee and Nikolai Simonenko, the director of its Middle East division —tried to counsel Taraki to take a more gradualist line, but he was both confident in his eventual success and aware that he risked being outflanked by Amin if he seemed to be back-pedalling on previous commitments.

Meanwhile, the PDPA was increasingly torn by internal disputes as the Khalq ('Masses') faction to which both Taraki and Amin belonged froze out Babrak Karmal's Parcham ('Banner') group. This began to tear apart the army, which represented the PDPA's main and vital source of support. Major General Zaplatin, a Soviet adviser to the Afghan army's political administration who had been asked by Ponomarev particularly to keep an eye open for such signs, found that even by May 1978, there was open discrimination against Parchamis in the military. In August, Babrak Karmal was effectively exiled to head the embassy in Prague, other colleagues being scattered to London, Belgrade, Tehran and Islamabad, and in November, he was accused of organising a coup against Taraki: the split in the PDPA had become open.

In March 1979, the regime's bid to introduce education for women sparked a revolt in the western city of Herat. The bulk of the government's 17th Infantry Division supported the mutiny and loyal troops took a week to suppress the uprising. Amongst the approximately 5,000 dead were 100 Soviets, including the wives and families of military advisers, hacked to death by the mob. Herat was to prove decisive: it stimulated the first serious contingency planning for intervention (either to stabilise the country or rescue Soviet nationals) and conditioned attitudes in Moscow to the 'savages' of Afghanistan.

The power of the regime — rooted largely in the armed forces — was draining away daily, not least given the role of the now excluded Parcham within the officer corps and the division of Khalq between supporters of Taraki and Amin. By the end of the year, desertions had more than halved the government army, from 90,000 to 40,000 as entire brigades began to join the rebels. The regime began bombarding Moscow and its agents in Kabul with a stream of requests for military assistance and matériel. In response, the commission sent General Epishev, head of the Military Political Administration, to assess the situation in April. Although Colonel General Volkogonov, one-time near-Stalinist and later born-again radical, exonerated him, it appears that, concerned with the political consequences of the fall of Kabul, Epishev felt assistance was warranted. As a result, arms transfers were stepped up and on 8 July, a battalion from the 105th Guards Airborne Division — the unit which eventually spearheaded the occupation — was secretly transferred to Bagram air force base, masquerading as air crew, to establish a secure airhead, whether for intervention or evacuation.

In August 1979, the Commission met again to hear reports from the Chief Military Adviser in Afghanistan, Lieutenant General Gorelov,

and the senior KGB officer in-country, Lieutenant General Ivanov, Gorelov counselled strongly against any deployments in Afghanistan, but Ivanov made a good case for the opposite. After all, Ivanov's career was somewhat becalmed, and to be at the centre of a major initiative receivi...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps and Tables

- Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Invasion

- PART ONE: THE VETERANS

- PART TWO: THE VICTIMS OF THE WAR

- PART THREE: THE WAR AND SOCIETY

- PART FOUR: THE WAR AND THE PROFESSIONAL SOLDIERS

- CONCLUSIONS

- Select Bibliography

- Index

Stili delle citazioni per Afghanistan

APA 6 Citation

Galeotti, M. (2012). Afghanistan (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/1621888/afghanistan-the-soviet-unions-last-war-pdf (Original work published 2012)

Chicago Citation

Galeotti, Mark. (2012) 2012. Afghanistan. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/1621888/afghanistan-the-soviet-unions-last-war-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Galeotti, M. (2012) Afghanistan. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/1621888/afghanistan-the-soviet-unions-last-war-pdf (Accessed: 14 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Galeotti, Mark. Afghanistan. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2012. Web. 14 Oct. 2022.