![]()

Chapter 1

Community Gardening: From Leisure to Social Action

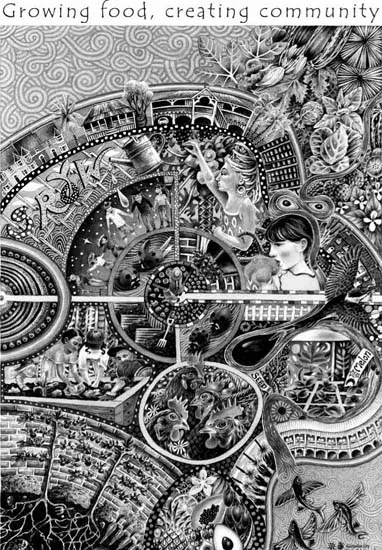

On the wall is a poster promoting community gardening. At its centre, a woman and child plant lettuces. They are surrounded by images of people and plants: A basket overflows with Aztec corn and tropical fruit. Brussels sprouts grow alongside sprawling native bushfoods. Heritage variety melons are sprouting in trays and beans are tagged for seed saving. People plant and weed, harvest and eat, and hold hands in the moonlight. A river flows past a brightly painted rainwater tank to where a sacred kingfisher flies downstream to the sea. The image is framed by rows of houses, each trailing leaves and vines as the garden’s growth becomes contagious.

There has been a resurgence of community gardening activity around the Western world over the past decade. Community gardens are places created by groups of people to grow food and community. But more than that, they are places where people come together to make things happen. Some community gardens involve just a handful of dedicated gardeners creating pockets of green in their local neighbourhood. Other community gardens host thousands of visitors each year and, like the garden in the poster, are venues for multiple activities. In these gardens, people contribute to food security, question the erosion of public space, conserve and improve urban environments, develop technologies of sustainable food production and urban living, foster community engagement and mutual support, engage in cultural maintenance and production, and create neighbourhood commons.

In Australia, community gardening has been adopted by divergent actors, from health agencies wanting to increase fruit and vegetable consumption to radical social movements seeking symbols of non-capitalist ways of relating and occupying space. The focus in this book is on community gardening as a way that people engage in collective social action. The book has developed in response to ten years of participant observation and interviews with leading community garden activists. In this time, I have found that people engage with community gardens for many reasons. I certainly don’t wish to argue that everyone who cultivates a plot at their local community garden is there because they’re seeking to create radical social change. However, I have found that for some, community gardens offer a unique opportunity to join with others, to make political claims and to make visions manifest in the landscape. Activism is a significant ingredient in community gardening praxis, and one that has thus far received an inadequate amount of attention. Viewing community gardens as sites of collective social action enables a more nuanced and complete understanding of community gardening and its potential contributions to understandings of activism, community, democracy and culture. It also invites reflection on the prefigurative practices of social movements that are seeking not only to draw attention to that which they oppose, but also to begin the work of building a counter-infrastructure of institutions and cultural practices. In this book I attempt to address the lack of empirical and theoretical attention given to community gardening in general and argue for the significance of community gardening as a socio-political practice. My particular focus is on understanding the unique barrowful of tools and techniques – the repertoire of collective action – used by community gardeners to enact social change. This in turn informs a critique of the limits of social movement theory in addressing movements whose tactics differ from the confrontational protests and large-scale events that are the focus of much social movement analysis.

Figure 1.1 Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network poster, distributed nationally in 2012

Source: Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network. Original watercolour painting by Lucy Everitt www.lucyeveritt.wordpress.com.

Community gardens grow in the fertile intersections between food politics and agrifood studies, environmentalism and urban social movements, policy and planning, social work and social action. They are spaces ripe for exploration of the ways people act together at the most local level while also seeking to grapple with processes operating at a transnational scale. So it is surprising that despite its significant growth and popularity, there has so far been very little systematic research on the Australian community gardening movement and little research internationally that considers community gardening as a means through which people engage in collective social action. Researching and writing this book has been my attempt to gain a greater understanding of the Australian community gardening movement. This movement is a site of innovation, having developed a suite of inventive practices and analyses that I believe deserve to be more richly known. It is perhaps possible to think of it as an heir to the tradition of the wider Australian environmental movement, which is recognised for the creativity and tactical innovation it has developed in grassroots campaigns to protect forests and oceans and in opposition to uranium mining and nuclear proliferation. The ingenuity of the Australian environment movement has influenced the repertoire of social movement tactics internationally, from the use of tripods in forest blockades to the formation of Green political parties1 (Hutton and Connors 1999, Wall 1999a, 1999b, Doyle 2000, Doherty 2002, Plows, Doherty and Wall 2004). Australian academics have also drawn on the particular experiences of Australian environmental movements in developing influential theoretical and philosophical works (Bürhs and Christoff 2006, see for example Eckersley 1992, Fox 1990, Salleh 1997, Plumwood 2002). It is my hope that readers outside Australia may find in this book a case study that, while grounded in the local and specific, also has clear resonances and connections with both activist praxis and academic analysis in an international context.

My intention in this introductory chapter is to widen the window through which we see community gardens, from one that opens onto community gardening as a form of leisure activity (with health and social benefits) to one that also offers a view to its role as a form of collective social action. Working towards this end, I will begin by describing three waves of community gardening activity that have occurred in Australia since the 1970s and offering a brief review of the literature on community gardening in Australia, the United Kingdom and North America.2 From here, I will turn my attention to the possibilities and implications of viewing community gardening through the lens of collective social action. I examine the various ways the practice of community gardening has been framed in terms palatable to governments and policy makers, and the simultaneous adoption of community gardening as a political performance by radical social movements. This incongruity raises a number of questions about community gardening as a practice concerned with both social service and collective social action. The remainder of the chapter is dedicated to discussing the particular questions that are the focus of this book, the case studies in which my research is grounded, and the theoretical and methodological frameworks that have informed my approach, particularly my use of social movement theory and of ethnography as activist research.

Community gardening in Australia

In order to set the scene, I’d like to begin with a brief account of the emergence of community gardening in Australia, the current state of the Australian community gardening movement and the existing research on community gardening in this country. Community gardens began growing around Australia in the late 1970s and early 80s. This first groundswell was followed by a second crop in the mid-1990s and community gardening has enjoyed another flush of growth between 2005 and the present. Several of the first community gardens in Australia were established in Melbourne between 1977 and 1981. Nunawading Community Garden is widely recognised as Australia’s first, though there may have been community gardens in Canberra and Adelaide before Nunawading was established. Early community gardens were also established in Perth in 1983 and Sydney in 1985.

Despite emerging around the country at a similar time, there were few connections among these early community gardens and many were unaware that the other gardens existed (Phillips 1996). Most of these first community gardens continue to flourish. In the mid-1990s a number of new community gardens began to grow alongside them. In 1994 several flagship projects were established, including Northey Street City Farm (Brisbane), East Perth City Farm (Perth), Wynn Vale Community Garden (Adelaide), Randwick Community Garden (Sydney) and the University of New South Wales Community Permaculture Garden (Sydney). During this period ties among community gardens strengthened and a national body, the Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network (ACFCGN) was established to support and advocate for community gardening. Between 2005 and 2012 there was a new surge of interest in community gardens, with many new gardens established, heightened public interest and community gardeners becoming increasingly organised. Attendance at Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network national conferences mushroomed from 70 in 2004 to over 750 in 2007. Coverage of community gardens in the media also proliferated, with numerous favourable stories in newspapers and magazines, on radio and television and online.

While it is clear that there has been significant growth in recent years, the full extent of community gardening activity in Australia has remained largely unmapped. Even the number of community gardens operating in Australia is not known with any precision. In 2010 the Australian City Farms and Community Gardens Network’s website3 listed contact details for 2124 established community gardens and mentioned others in development. While this was the most comprehensive listing of community gardens in Australia, it had significant gaps and was likely a gross underestimate of the number of community gardens existing at that time.5 Significantly, for example, the list did not include any of the gardens in Melbourne, a city in which there were at least 60 community gardens growing in 2010.

The recent growth of interest in community gardens can be partly attributed to the increased prominence of food issues and the development and popularisation of a range of alternative agrifood initiatives, such as farmers’ markets, community supported agriculture (CSA) and consumers’ co-operatives. Associated perspectives such as slow food (Petrini 2007), community food security (Winne 2009), food justice (Levkoe 2006), civic agriculture (Lyson 2004) and food sovereignty (Wittman, Desmarais and Wiebe 2010) have provided new frames for promoting community gardening. Community gardeners have become increasingly allied with broader food movements and have successfully positioned themselves as a form of practical action on issues of food security, sustainable food production, fossil fuel dependence, climate change and water conservation. For the media, community gardens have provided bucolic photo opportunities and fodder for stories about children learning about how food is grown. Positive magazine and television coverage has also played a role in raising the profile of community gardens.

Community garden research and analysis

There has been little research, and even less analysis, on community gardens in their uniquely Australian manifestation. In the 1980s and 90s the field consisted of two reports (Eliott 1983, Phillips 1996) describing the emergence of community gardening in Australia and profiling a number of sites. From the mid-1990s to around 2010, most of the research on community gardens in Australia was conducted by honours and masters students (Barnett 1996, Sullivan 1997, Stocker and Barnett 1998, Crabtree 1999, Gelsi 1999, Joss 2003, Harris 2008, Hujber 2008, Green 2009). These student papers provide important descriptive data, often about individual gardens, and some useful analysis. Refereed publications have been few and far between (Stocker and Barnett 1998, Perkins and Lynn 2000, Corkery 2004b, Somerset, Ball, Flett and Ceissman 2005, Kingsley and Townsend 2006, Kingsley, Townsend and Henderson-Wilson 2009). When a group of researchers at the University of New South Wales (Bartolomei, Corkery, Judd and Thompson 2003) released the report, A Bountiful Harvest: Community Gardens and Neighbourhood Renewal in Waterloo Sydney, it was promoted as ‘the first significant study of community gardens in Australia’. This publication detailed a qualitative interdisciplinary research project on the role of community gardens in a Sydney public housing estate, focusing on community development and neighbourhood improvement (see also Corkery 2004a, 2004b). Academic interest in Australian community gardens has recently increased and the first academic conference about community gardening was held at the University of Canberra in October 2010 (see Turner, Henryks and Pearson 2010).

In North America, and to a lesser extent the United Kingdom, there has been a comparative burgeoning of research on community gardens. While the experiences of community gardeners in these regions have much in common with their Australian counterparts, it is important to note significant differences among them, particularly with regard to patterns of urban land use and histories of government urban agriculture programs. United States community gardens are most commonly associated with urban blight sites and the process of abandonment of inner-city properties (Warner 1987: 5). They are frequently interpreted as grassroots responses to the processes of poverty and urban decay (Fox, Koeppel and Kellam 1985, Warner 1987, Schmelzkopf 1995, Carlsson and Manning 2010). Carlsson (2008: 92) evokes the environments in which early gardens were planted and nurtured in vacant lots ‘amidst crumbling, abandoned tenements full of heroin shooting galleries, gun-toting dealers, and high levels of street crime and mindless vandalism’. The complex relationship between community garden development and gentrification has been important in accounts of US community gardening history. Australia’s urban and suburban land-use patterns have not followed the same trajectory as those of the US and while some Australian community gardens are in areas affected by poverty and urban neglect, reclaimed blight sites are not common locations for community gardens.6 Another significant difference between the Australian and US and UK community gardening movements is the role of governments. In the United States, writers argue that the influence of government campaigns during Wartime was significant to the development of community gardening (Warner 1987, Kurtz 2001, Lawson 2005). More recent government-funded programs have supported the development of many contemporary gardens. In contrast, other than the school gardening push of the Federation era (Hunt 2001, Libby 2001), there is no real history of Australian government imperatives for communal food cultivation on public land and community gardens in this country have not received government funding or support on anywhere near the scale of their US and UK counterparts. While government and quasi-government agencies have recently begun to run community garden programs, most gardens in Australia begin as participant-initiated projects and receive little government support or intervention. In addition, ‘community garden’ is often defined more broadly in US literature than in Australian practice. For example, in Australia community gardening is understood to involve food production, whereas in the United States, some ‘community gardens’ grow only ornamental plants (this discussion is taken up in detail in Chapter 2).

In North America and the United Kingdom, community gardens have caught the interest of scholars across a number of disciplines: leisure studies and health, urban and agrifood studies, sociology, economics and anthropology. Despite being produced across several disciplines, the focus in literature on community gardening in the ‘West’ has been reasonably narrow. Most of what has been published has been either descriptive and/or focused on enumerating the benefits of community gardening. Academics who have thought and written about community gardens have taken their social role seriously and almost all have designed their research to be of use to community gardeners. Much of the literature produced about community gardens has aimed to strengthen the legitimacy of community gardening and to identify and demonstrate the range of tangible outcomes community gardens provide to individuals and communities. Partial, but nonetheless useful, views of community gardening have been provided by accounts of them as sites of leisure,7 health promotion,8 community development,9 urban greening and sustainability,10 the development of social capital,11 learning and skills development,12 cultural maintenance and production,13 inter-cultural interaction,14 urban agriculture15 and self-provisioning in times of economic need.16 Each of these perspectives reveals evidence of the impacts and significance of community gardens. The focus on benefits has generated a lite...