![]()

1 Perspectives on Rhythmic Movement

Abstract

Rhythmic activity, such as bipedal and quadrupedal locomotion, obviously has a neural substrate. It is not clear, however, that a neurally oriented analysis of rhythmic movement will reveal its mechanism. Nor is it clear that the closely related motor-program perspective, with its emphasis on symbol strings, can provide much help in this matter. Arbitrariness plagues both of the orthodox perspectives on rhythmic movement, given their mutual lack of principled constraints. The first chapter sketches a law-based approach to animal movement, intimating how an account of biological phenomena might be fashioned that is methodologically continuous with the physical sciences. It identifies a central claim that natural phenomena at all scales are organized by a common set of (physical) strategies, although each scale may exhibit unique regularities. At their own scale, living systems are open to exchanges of matter and energy, they are self-sustaining and nondeterminate and they are dominated by information more than they are by forces. These characteristics of living things are discussed as factors that shape the regularities defining a physics of animal movement.

1.1. Rhythmic Phenomena in Biology

Rhythmic phenomena abound in biology at all levels of analysis (Aschoff, 1979; Berridge, Rupp, & Treherne, 1979; Iberall, 1972; Winfree, 1980). At the behavioral level, rhythms can be observed in which the entire body or parts of the body move in a cyclic, repetitive fashion. Running, swimming, flying, breathing, chewing, and grooming are the most cited examples, but rhythmic behaviors need not be so stereotypic, a fact attested to by the musical accomplishments of humans.

Although they are commonplace, behavioral rhythmicities are not well understood. To date, the efforts of neuroscience to explain behavior such as locomotion have been shaped in part by the issue of whether the behavior is generated centrally, by properties intrinsic to the central nervous system, or whether it is achieved by sensory feedback from moving parts of the body (Delcomyn, 1980; Evarts, Bizzi, Burke, Delong & Thach, 1971). Conventional wisdom and the weight of evidence favor the view of central pattern generation: A repetitive rhythmic output is said to be the product of a neural "oscillator" conceived either as a single pacemaker neuron (e.g., Maynard, 1972) or as a network of neurons (e.g., Wilson & Waldron, 1968).

The pioneering work of von Hoist (1935/1973), an early proponent of central-pattern generators, addressed the problem of the coupling of two or more neural oscillators. This problem arises as soon as the focus of inquiry into locomotion shifts from the rhythmicity of a single limb or body segment to the rhythmicity of the locomotory act in full. Examination of the coupled rhythmic movements of the pectoral and dorsal fins of fish that swim with the main body axis immobile led to the identification of two major classes of mutual influence. One of these influences, termed "superposition," is manifest (primarily) in the amplitude of the rhythmic movements, while the other influence, termed the "magnet effect," is manifest in their frequencies. Treating the generators of individual fin rhythmicity as automatisms, von Hoist (1935/1973) regarded the magnet effect as the tendency of automatisms to attract each other to their respective preferred tempos, von Hoist regarded the magnet effect as general: Not only did it operate in the coupling of individual automatisms but it operated in the coupling of the cells that comprise an individual automatism. Further, he observed that when two or more automatisms converged on a common, stable frequency, they lost nothing of their individuality (see also Arsharvskii, Kots, Orlovskii, Rodionov & Shik, 1965; Shik & Orlovskii, 1965). Individual preference for this or that frequency remained, suggesting that the coordinated rhythmic states exhibited by the collection of rhythm generators comprised continuously competing tendencies among components. Although some of von Hoist's empirical claims have been questioned (e.g., Roberts, 1967) the foregoing observations remain secure (Stein, 1977). In retrospect, they are observations that place locomotion squarely in the class of cooperative phenomena (Haken, 1977). How is this locomotory instance of cooperativity to be understood?

1.2. Hard-Molded and Soft-Molded Rhythmic Movements

Where explanations of rhythmic behavior such as locomotion have been neural in their focus, the tendency has been to regard the behavior in question as hard molded (hard wired, hard geared, hard coupled, hard guided, and hard algorithmed). These terms, borrowed from engineering, refer, in general, to the directing of "signals" along rigidly determined kinematic paths. The commonly proposed neural mechanisms, as noted, are single cells or ensembles of cells specialized for the generation of behavioral rhythmicities. Of the two, the specialized ensemble or network is thought to be the more general mechanism. A central pattern generator works, presumably, by guiding the chemico-electrical field along hard constraints (specific neural pathways linking specific neural elements) to produce periodic tensile states in the associated musculature. Selverston (1980) has argued that understanding how a hard-molded central pattern generator works for any given instance of rhythmicity is equated with identifying all of the ensemble's neural elements, all of the membrane and synaptic properties of those elements, and all of the connections among them. Putting aside doubts about the success of such a program (see Selverston, 1980, and commentaries) there are questions of its propriety. Rhythmic motions of the body can be, and frequently are, soft molded (soft wired, soft geared, soft coupled, soft guided, and soft algorithmed), which is to say, loosely speaking, that a biokinematic system with periodic behavior can be assembled temporarily and for a particular purpose from whatever neural and skeletomuscular elements are available and befitting the task.

Both hard and soft construction of rhythmic movements must follow from principles that govern the cyclic mode of biological organization in general. An account of hard-molded periodic behavior might be pursued without identifying these principles, but a satisfactory account of soft-molded periodic behavior cannot be attempted without them. In their basic format these principles are not likely to be unique to biology. An educated guess is that they are to be numbered among the few universally generalizable principles of physics (Morowitz, 1968, 1978; Yates & Iberall, 1973). Understanding the production of rhythmic movements that are softly molded from biological materials must rest on an understanding of how a specific set of strategies can be realized in distinct morphological settings subject to very general laws (cf. Iberall & Soodak, 1986). A program for understanding soft-molded behavior contrasts with that identified above for hard-molded rhythmic behavior in that it must give priority to physical law.

On at least two counts, it would seem that a law-oriented program is essential to the success of a neural-oriented program, regardless of whether the latter's target is an understanding of hard, or hard and soft, instances of rhythmic behaviors. First, there is the issue of how to constrain rationally the choice of relevant properties to be studied. Ideally one wishes to manipulate those parameters of the central pattern generator that govern its operation. Unfortunately, the parameter set of a neural ensemble contains, by some counts, 46 entries that could be relevant to a neurophysiological explanation (Bullock, 1975). Principles beyond those of neurophysiology are required to guide the selection of parameters. Second, there is the issue of how to explain the characteristic quantities of a rhythmic behavior—for example, its period, amplitude, and energy per cycle. These quantities cannot be rationalized on neural considerations alone.

1.3. The Concept of Motor Program

It is a small step from the concept of central pattern generator to that of motor program. Often the two concepts are used interchangeably. Like the concept of central pattern generator, the motor-program concept is a "centralist" counterpoint to the "peripheralist" treatment of rhythmic movement (as a concatenation of reflexively mediated, afferent-efferent connections). At the core of the centralist view is the recognition that the spatiotemporal details of a cycle of locomotion appear, in very large part, to be anticipated. By the peripheralist account, the successive and adjacent order of the skeletomuscular variables and their magnitudes are determined during the cyclic movement on a moment-to-moment basis. In contrast, the centralist account regards the successive and adjacent order of the skeletomuscular variables and the ballpark magnitudes of these variables as being determined prior to the cyclic movement. There are moment-to-moment influences, but these are reflected mainly in the magnitudes of the variables (as a fine tuning) and minimally in their ordering. Some proponents of the centralist view (e.g., Keele, 1968) have ruled out fed-back influences. But as others have pointed out, this prohibition is unwarranted (e.g., Reed, 1982; Schmidt, 1982) and inconsistent with the concept of program (MacKay, 1980). By definition, a program must receive (negations and affirmations) as well as give (instructions).

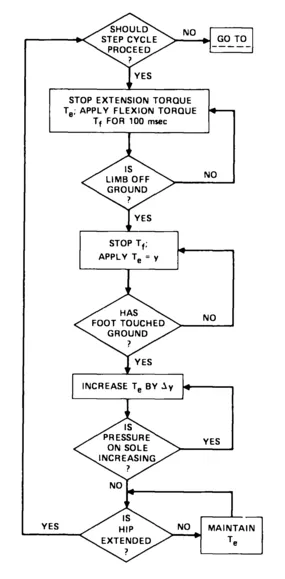

An example of a programming formulation of a step cycle in locomotion is provided by MacKay (1980) and reproduced in Figure 1.1. As can be seen, the kinematic and kinetic details are ordered by a sequence of commands and queries. The commands and queries are symbol strings that guide the performance of the step cycle: They function to constrain the continuous dynamical process by which the step cycle is realized. The contrast between rate-independent symbol strings and rate-dependent dynamical processes is said by Pattee (1973, 1977, 1979) to identify a complementarity principle. For Pattee, this particular complementarity is the hallmark of living systems. His argument is that living systems operate in two modes, the symbolic and the dynamic, which are incompatible and irreducible. Consequently, for Pattee, understanding biological phenomena (such as rhythmic movements) rests with the elaboration of this complementarity. By Pattee's view, the motor-program approach is flawed to the extent that it emphasizes the discrete symbolic mode to the neglect of the continuous dynamical mode. The phenomena in question are the result of a mutuality between the two modes.

FIGURE 1.1. A MOTOR PROGRAM PERSPECTIVE ON THE LOCOMOTORY STEP CYCLE (adapted from MacKay, 1980).

There is, however, an inequality between the discrete symbolic and continuous dynamical modes that has to be appreciated. Nature uses the symbolic mode—nonholonomic, nonintegrable constraints (see Pattee, 1983, 1986; and Appendix A)—sparingly. Dynamics are used to the fullest, wherever and whenever, to achieve characteristic biological effects (see also Gould, 1966; Gould & Lewontin, 1979). Symbol strings are used, now and then, to direct dynamical processes and to limit their complexity—in other words, to trim the dynamical degrees of freedom. In Figure 1.1 the opposite strategy is at work. Very many nonholonomic constraints are exploited to achieve ("to explain") the kinetic and kinematic regularities of a locomotory step cycle. The question of how the dynamics, properly construed for the biological scale, might fashion the phenomenon is ignored. Also ignored is the question of how the symbol strings interface with the dynamics.

Pattee's analysis is an important one (see Carello, Turvey, Kugler, & Shaw, 1984) for the motor-program perspective (given that perspective's emphasis on the symbolic mode) because it suggests that only in the working out of the physics of a regularity can one identify the nature and type of symbol strings (nonholonomic constraints) needed to complete the explanation. Beginning with the symbolic mode, and adhering strictly to it, invites an account (of coordinated movement, for example) that will be plagued by arbitrariness. Beginning with the dynamical mode—that is, taking a law-based approach—and pursuing it earnestly promises an account that will be principled.

1.4. Physical Biology

Broadly construed, a law-oriented program is an attempt to give an account of biological phenomena (such as rhythmic movement) that is continuous with physical methodologies. A physical approach to biology views living systems as ordinary physical systems of great complexity; all biophysical transformations must ...