![]()

Part I

Origins

![]()

1

Why Global Citizenship?

Globalization on Main Street

“We didn’t used to feel this way. But we do now.” These words, written in a letter to the editor of the local newspaper, capture how residents of Hickory, a small manufacturing town in the American Midwest, are processing the distress, anxiety, and even fear engendered by recent demographic and economic changes.1

This quiet little town, its wide Main Street dotted with quaint shops and turn of the century architecture, conjures images from Sinclair Lewis’ novel titled from that street name. This is a place where people stroll the sidewalks on Main Street, stop to talk to neighbors about last night’s high school basketball game, poke into shops to say hello, or swing by the post office for the latest town gossip. It’s a place of familiarity where residents walk into the coffee shop and the owner knows their order without asking. It seems hardly a place where global flows of capital and people could restructure its entire complexion; but that is exactly what has happened.

The population of Hickory has doubled since 1980. A large portion of that growth, especially recently, is due to an influx of immigrants; the Hispanic/Latino population has more than quadrupled in less than two decades. The town’s population was over 97 percent white in 1980. The Latino population approaches 25 percent today. Immigrants come to Hickory primarily for manufacturing jobs (42 percent of all jobs in the town are in manufacturing). The manufacturing industry in this part of the country was hit particularly hard by the recent economic downturn; unemployment reached nearly 20 percent in Hickory in 2009, one of the highest rates in the country. Some large factories closed their doors and moved to Mexico for cheaper labor. According to some locals, other factories have turned to employing large numbers of undocumented immigrants, causing significant decreases in wages and higher unemployment for the white working class.

These rapid transformations, intimately connected to globalization processes that cognitively seem so distant, evoke the anxieties captured by the letter to the editor above. For a place that was considered a “sundown town” (where people of color had to leave by sunset) in the fifties and sixties and where a Ku Klux Klan rally marched down Main Street in the late nineties, dealing with cultural differences and an invading global economy is a significant challenge.

Economic and demographic changes like these, of course, have immediate effects on local schools. The Hickory School District went from less than 7 percent minority population to 48 percent in the last fifteen years. At Hickory High School, 35 percent of the student population are Hispanic/Latino. The high school has seen its portion of students qualifying for free and reduced lunch increase from 15 to 50 percent in little more than a decade.

Test scores have been falling, and in the high stakes environment of No Child Left Behind legislation, this trend is a significant threat that many residents believe is directly related to immigration. “Ever wonder why the state test scores are what they are?” wrote a disgruntled resident in a letter to the editor of Hickory’s newspaper. “English was not meant to be a second language in this country.” Jill, an English teacher at Hickory High School, noted that the last ten years brought “a huge influx in immigrants to this area, mostly from Mexico but also other Latin American countries, Pakistan, and even some from African countries.” Jill says this brought divisiveness in the community and it was “harder for the working class— the blue-collar and poverty students” because now they “have more competition for jobs.” Anxiety runs deep in this little town. But many also see these recent transformations as an opportunity.

As Hickory races headlong on its crash course with globalization, teachers like Jill and others at the high school firmly believe that they are living in a fundamentally new and different world, and their job is to prepare students for it. In order to address these issues, the school recently adopted a new curriculum and program focus that seeks to develop “international mindedness” in students so that they can become “global citizens” and “help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect.” They hope that these reforms will help their students imagine themselves as part of a global community while preparing them for a rapidly changing global economy.

When teachers at Hickory High School were asked why they adopted this particular program in the face of the recent changes, they explained global citizenship education as a way to channel the anxieties about these transformations into opportunities, and beyond that, as a way to make a better world. In part, this means capitalizing on opportunities for economic prosperity in the global market that may otherwise leave towns like Hickory behind. The high unemployment rate makes many teachers feel a moral obligation to help students prepare for the very competitive global economy. Jill understands that global forces are transforming her students’ futures. She is working to help them embrace these changes: “We’re trying to expand the opportunities they have in the global economy.” Jill believes it is crucial for her students to understand global transformations. She says, “I mean, it’s pretty terrifying if you think about the economy worldwide and how things are structured; the idea of a manufacturing job just really isn’t going to sustain them for sixty years of employment like it did their parents or grandparents.” She thinks it is important to explain to her students “you’re not competing with the kid sitting next to you for a job. You’re competing with a student in China or in India.” Jill’s students need to be prepared for that, she believes, so they can “make the right choices in school” in order to gain “the skills and knowledge you will need to succeed.” In Jill’s mind, anxieties about global economic transformations must be turned into opportunities for her students to develop the human capital—the global competencies—necessary for prospering in a competitive new world. If her students rely on the old skills and knowledge that was enough to sustain their parents and grandparents in manufacturing jobs, students from China and India will gain the global competencies necessary to win the available jobs in the global economy, and Jill’s students will be left behind.

But equipping students with global competencies to prepare them for recent economic changes is not the only motive in adopting global citizenship education. For Todd, an assistant principal, growing diversity is an opportunity to cultivate an ethical sensibility—a global consciousness— that is increasingly important. He recognizes “that the mom who’s lost a job is looking for somebody to blame, and so she blames the immigrants.” He gets parents in his office who say that “immigration is the most god-awful thing that’s ever happened to Hickory, and if we could only get rid of ‘them,’ we would be a better school and a better community.” Todd understands these reactions to the changes, but he wants to embrace an alternative path to a better community, and even a better world. He sees the new diversity of the student body as a strength, especially in light of the global processes that have created it. He says that one of the “gifts” Hickory can give its students is the understanding that cultural differences exist: “not everybody thinks like you do, and that around the world, there are these different viewpoints and you have to evaluate them and live with them.” Noting that a certain group in town sees “diversity as a problem and not as an opportunity,” Todd points out that the school made “a fairly conscious decision to say that we’re going to celebrate the diversity and use it to the advantage of our students.” He wants the students to know “that this is the world you live in, that you are going to have to figure out how to get along with all kinds of people in all kinds of places.” These are not empty platitudes for Todd; he has spent time teaching in Haiti and Puerto Rico and has adopted several children from countries around the world. In his mind, people become better human beings through experiencing and understanding cultural difference. This is the essence of a global consciousness that teachers believe to be essential for making a better world.

One of his colleagues, a biology teacher named Thomas, feels that there is something deeply ingrained in the human condition that draws different people together to maximize human potential. Tom points out that the rapidly shrinking world—caused by technology, media, and immigration, “makes some problems that seem to be ‘theirs’ or ‘others’ no longer that.” He wants his students to develop a consciousness that understands the shared problems, and shared fate, of the entire human race:

Their problems become ours, and we as a community of people, be that here in Hickory or be that in our State or these United States or the world, we can’t begin to reach our full potential unless we can do it in the context of the larger and larger community, and we thus have an obligation to understand the global community, and we should have a personal stake in that because we cannot reach our full potential as individuals, as a group of people, unless we can do it within the context of the broader community. And right now, for me, that’s the global community.

In order to help his students reach their full human potential in the context of the global community, Thomas led a trip with students to New Orleans a few months after Hurricane Katrina and was planning a trip for the upcoming year to Haiti. Furthermore, as a biology teacher, Thomas wants his students to realize that global problems, such as climate change, really affect their lives even in a “remote” place like Hickory and connect them to a broader humanity that transcends cultural differences: “changes that are occurring in the environment are affecting others and others’ activities may be affecting us, and so in terms of the biosphere, we’re in this thing together, and we have to agree as humans that we want to make our biosphere a better place.” For Thomas and his efforts in the classroom at Hickory High School, the realities of the global community make demands on the human race to reach its full potential and to make the world “a better place.”

Another English teacher, Robert, when explaining why they adopted the international curriculum program, captured the sentiments of many teachers at Hickory: “When people can come together and really experience and appreciate other cultures, it makes them more globally aware and that understanding and appreciation for other cultures will eventually turn towards a better world. That’s what we’re trying to do here.”

For teachers in Hickory, the “better world” that global citizenship education will bring includes both global consciousness and global competencies. The town of Hickory, like many places around the world, is faced with anxieties about global economic transformations and increasing cultural diversity. Faced with these very palpable changes, teachers believe focusing on global citizenship will expand students’ consciousness—their ethical sensibilities—and their competencies—skills needed for economic opportunities—to prepare them for cosmopolitan thriving in a global society.

The Rise of Global Citizenship Education

The story of Hickory plays itself out around the country and around the globe. While the particulars may differ, the underlying forces are familiar. Although in its incipient stages and with still many schools yet to embrace it, global citizenship education is nonetheless one of the fastest growing reforms in education. A large and highly influential movement from various institutional arenas lies behind its rapid growth in the United States and around the world. Educators, scholars, politicians, and business people are embracing global citizenship education in order to prepare the next generation for the twenty-first-century world, and the discourses of both consciousness and competencies are evident in this widespread embrace.

Scholars from many different disciplines—philosophy, political theory, sociology, and education—are embracing versions of global citizenship education as the solution to various worldwide problems. Noted philosophers such as Martha Nussbaum (2002) and Kwame Anthony Appiah (2005) have each offered visions for a “cosmopolitan” education to create “citizens of the world” who will embrace a moral consciousness that transcends divisive identities as part of a global humanity, respecting and tolerating the “other” while working towards a more just and peaceful world. This scholarly work is highly theoretical, and for the most part it emphasizes the global consciousness features of global citizenship education. But as these ideas filter into the world of politicians and educational policies, we see a blend of both consciousness and competencies evident in places like Hickory.

Over thirty-five states in the U.S. have an official state-level office, legislation, curriculum standard, or program dedicated to “international education” (Asia Society 2008a). While some states, such as New York, began their programs two decades ago, twenty-nine added their initiatives in the last ten years. States like California and New York have had programs for some time, but less expected states such as South Carolina, Kansas, and Nebraska all have extensive efforts. Programs include teacher exchanges, sister schools in other countries, increased foreign language requirements, and adding new languages like Arabic and Mandarin. The state in which Hickory High School is located, for instance, has such an office in its Department of Education; Hickory was able to apply for a grant to alleviate some of the costs associated with making curricular changes. As one teacher who led the effort recalled, the availability of such a grant was an important factor in securing the school administration’s approval for the change.

The federal government is also involved in encouraging a more global focus in American schools. Much like the teachers in Hickory, government officials are interested in responding to anxieties about cultural differences and opportunities for economic prosperity, and they draw on both the discourse of consciousness and the discourse of competencies. A joint effort between the U.S. Departments of Education and State, begun in 2000, sponsors an annual “International Education Week” to prepare students to live in “a diverse and tolerant society and succeed in a global economy.” In May of 2009 Senators Rockefeller and Boxer introduced a bill called the “21st Century Skill Incentive Act” to give states matching grants for adopting a 21st Century Skills Framework, including “global awareness.” President Obama signaled support for such efforts in a signature “education speech” during his first months in office, calling upon teachers to develop “21st century skills” for the new economy like “problem-solving and critical thinking and entrepreneurship and creativity.”

One of the worldwide leaders in these developments, the International Baccalaureate Organisation, based in Geneva, Switzerland, has experienced a rapid rise in interest for their school curriculums that combine rigorous study with an “international” focus that seeks to open the minds of students to global differences, problems, and realities that face the human race in the twenty-first century. The organization has grown from just thirty-two programs in 1977 to over 4,400 in 2012. This is the program that Hickory adopted. Steeped in the language of skills and competencies for the global economy, it has rapidly expanded around the world in the last decade, especially in public schools in the United States and the global south. Another group of schools with a similar focus, known as the UNESCO Associated Schools Project, has experienced rapid growth around the world and is now located in 130 countries (Suarez, Ramirez, and Koo 2009). Additionally, primary and secondary schools with phrases like “international studies” and “global citizenship” in their names have sprung up in the last decade all over the United States, from Brooklyn to Chicago, from Hollywood, Florida, to Eugene, Oregon.

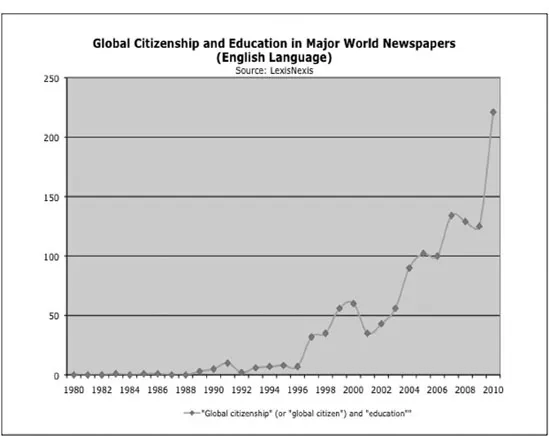

In the United States, one recent survey of social studies teachers showed nearly 60 percent saying that global citizenship was “absolutely essential” for civics education, and this majority existed in both wealthy schools and schools serving disadvantaged populations (Farkas and Duffet 2010). The public consciousness also seems to be more enamored with “global citizenship” and education, as demonstrated by the rapid increase in newspaper references in the last decade (Figure 1.1). While such measures are inherently limited, the virtual nonexistence of the term in public discourse until a decade ago suggests a significant shift in the popular imagination.

Figure 1.1 Global citizenship and education in major world newspapers.

The Institutional Ecology of Global Citizenship Education

Global citizenship education is on the rise, and its growth is not merely accidental. A town like Hickory does not make these changes in its school in isolation from larger social, cultural, and political forces. Global citizenship education does not experience such significant and rapid growth in a cultural vacuum. In fact, educational changes like these are never merely about the hopes and dreams of individual teachers in individual schools like Hickory. As already evident, such changes take place in a larger environment of institutions—governments, school districts, teacher unions, foundations, nongovernmental organizations—and the cultural legitimacy of such reforms is usually dependent on the strength of these larger institutional resources and networks. It is important to understand these overlapping networks of institutions that support the rise of global citizenship education because it is precisely this institutional ecology that accounts for the its rapid rise and prominence as a significant force in educational reform.

The International Baccalaureate Organisation (IBO) is one of the key institutional actors in this study. Seven of the ten high schools sampled for this study, including Hickory, use the International Baccalaureate Program as their...