The Rise of Projects and Project Complexity

Both academic and popular literature suggest that organizing through projects is on the increase, a process termed ‘projectification’ (Midler, 1995; Grabher, 2002) or ‘projectisation’ (Ekstedt et al., 1999). Bee and Bee (1998) suggest that this move towards project working is a response to the changing environment in which companies operate. Ekstedt et. al (1999) refer to this project-based perspective as ‘neo-industrial organizing’. Castells (2002 EGOS address) has referred to projects as the new mode of organization in the networked economy. Turner (1999) estimates that project working in the UK accounts for £300 billion per annum and 27 million person-years of effort, while Maylor (2010) reports that many managers have dual line and project management responsibilities and may spend more than half of their time on projects or project-related work. Others have pointed to the concomitant rise of the project management profession and the numbers of practicing ‘project managers’ (Lundin and Hartman, 2000; Morris and Pinto, 2004), with over 300,000 project managers worldwide having achieved Project Management Professional certification from the Project Management Institute by early 2009 (Pinto, 2010).

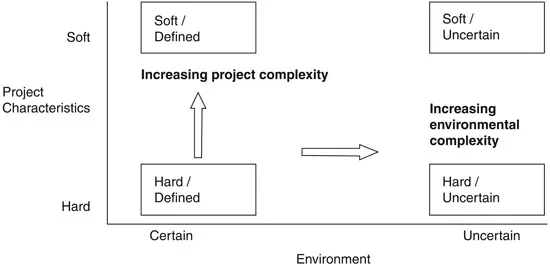

As the project mode of delivery has spread, complexity has simultaneously increased, at least for some classes of project (Williams, 2002; Vidal and Marle, 2008). For example, as the delivery of major infrastructures, products, systems and services is increasingly accomplished through projects, the difficulties (as well as the advantages) associated with this way of organizing and operating have become clearer. This is particularly so in the case of large capital projects which are characterized by the technological complexity of the product itself and the complex nature of the context of the project (in terms of the supply networks, financing, market and regulatory environment) (see Jaafari, 2004). Indeed, increasing complexity in capital projects can be seen as related to both increased project complexity and increased environmental complexity (see Figure 1.1).

Since we conducted our research, a growing interest in the application of the concept of complexity in the project management field has become apparent (Cooke-Davies et al., 2007). Geraldi and others have pointed to two streams of research in this area: research considering ‘complexity in projects’ and research identifying ‘complexity of projects’ (Geraldi, 2007; Geraldi et al., 2011). Our use of the term ‘complex project’ in this book is consistent with what Morris (1994) has termed ‘major projects’, although the reverse is not necessarily the case as not all major projects are complex;

Figure 1.1 Projects classified according to project and environmental complexity

Source: derived from Jaafari (2004)

many are just big. The kinds of projects in which we are interested here are therefore those that tend towards having ‘soft’, or ambiguous and unclear, socio-technical characteristics and uncertain environmental contexts due to changing market and/or regulatory conditions.

Sources of Complexity in Large Projects

It is argued that a range of factors can be identified that give rise to increased levels of complexity in projects (Geraldi et al., 2011). Such complexity is both organizational as well as technological in nature and involves:

- the forging by contractors of new relationships with clients;

- the development of new organizational forms (for example, multidisciplinary team-based working amongst project designers);

- new and extended relationships with suppliers and a range of intermediaries (consultants, regulatory agencies and bodies, design houses, financiers, etc.); and

- a plethora of other interfaces between the content and process of project delivery and its internal business and external economic, regulatory and societal contexts.

All of these pose new problems for the classic project management concern of how to manage uncertainty and risk. However, as the envelope of the project extends to include the impact of the client’s business strategy on the project and the provision of services to the client’s customers, this may give rise to ambiguity in project definition. Making sense of ambiguity is not well served by the conventional project management body of knowledge. In this chapter we identify the following sources of complexity in projects: technology, organization, customers or clients, environment and management. We also refer to the additional complexity resulting from the move into long-term service-led projects, the conceptual implications of which for the management process we explore further in the next chapter.

Technology

Technology has emerged as a major challenge to the effective management of projects (Morris and Pinto, 2004: 383). Technology is a key source of complexity in many types of major projects, including those involving large-scale information systems development such as telecommunications systems, major IT infrastructures such as those for the UK National Health Service, as well as more engineering-based projects such as those in the defence, aerospace, rail, marine, offshore and other specialized sectors of capital goods. Indeed, for some projects, technological complexity has been seen as their defining feature. One definition sees such complexity as deriving from such things as the number of customized components, sub-components and tailored systems in the product. Technological complexity has also been measured in terms of the design options available, the amount of new technology or new knowledge required, numbers of materials used, scale of finance and other related factors (see Hobday, 1998; Wang and Von Tunzelmann, 2000).

The term ‘CoPS’ (complex product systems) has been coined for a particular category of technologically complex projects, which some consider represents a significant mode of delivery in the capital goods sector (Hobday et al., 2000). These can be defined as:

‘… high cost, technology-intensive, customised capital goods, systems, networks, control units, software packages, constructs and services…. CoPS are, strictly speaking, a subset of capital goods: the high technology capital goods, which underpin the provision of services and manufacturing—the “technological backbone” of the modern economy’ (Hobday et al., 2000: 793–794).

Examples of CoPS provided by Hobday (1998) include telecommunications exchanges, flight simulators, aircraft engines, avionics and trains. These projects, it has been argued, are particularly worthy of close attention owing to their fundamental importance to the UK economy (Hobday et al., 2000; Acha et al., 2004). Like all projects, CoPS projects are usually one-off, or few-off; they are never mass produced. While it is acknowledged that on completion CoPS can be revisited for further development, CoPS projects are usually seen as temporary arrangements that will be scaled down or dismantled once the physical project is completed (Hobday, 1998: 706).

Organization

Complex projects are rarely, if ever, deliverable wholly or even mainly by a single organization. If we take the example of CoPS, Hobday and his colleagues observe that, owing to the complexity of these types of product systems, few firms have all the competencies and capabilities required to produce CoPS independently. As a result, there is a substantial level of outsourcing so that the project becomes a temporary coalition (Barlow, 2000: 974) or network of organizations (who may have differing objectives for their involvement) requiring the management of extensive cross-firm coordination across a whole range of business and organizational boundaries (e.g., technological, legal, administrative, human resource and so on). By definition CoPS are technologically complex and this, it is claimed, results in management or organizational systems that are similarly complex (Wang and Von Tunzelmann, 2000). For authors such as Baccarini (1996) project complexity is simply a function of the variety and diversity of technologies and organizational networks and the interdependencies arising from them.

However, whilst the outsourcing of much activity could be seen as a necessary response to a broad spectrum of technological and commercial factors, we would suggest that organizational complexity (and indeed other sources of complexity) should not be regarded purely as a function of levels of technological complexity. Network forms of organizing have spawned a large amount of literature (see Thompson, 2003, for a review), and there are many who would argue that such organizational complexity is not a derivative of technological complexity at all. Indeed, at best, technology can be seen as a ‘trigger’ for such organizational forms, rather than as a determinant of them (Boddy and Gunson, 1996; McLoughlin and Clark, 1994). The precise form of project network is thus likely to be variable even where the type and level of technological complexity are similar. Organizational complexity is also seen in the formation of multi-organizational partnerships where the project boundary cuts across organizational boundaries. Managing within networks, as opposed to managing through the control of hierarchies (whether internal or extended through contracting with supply chains), is both challenging and necessary. Contractors do not control their clients’ customers but may need to extend their influence over them or be influenced by them. Such networks may be animated by complex contractual arrangements, consortium agreements and nonbinding partnerships or mediated by third parties, as in consumer studies or focus groups.

Customers or Clients

If technological and organizational complexities can be seen as part of the supply-side factors that can increase the complexity of projects, then the nature of the markets for such projects is a key demand-side factor. Indeed, the relative power of customers vis-à-vis the deliverers of major projects is a key dynamic. One argument for the increased complexity of projects is that customers are now willing and able to exert far more pressure on manufacturers and contractors to offer new and more comprehensive services in ways that distribute the costs, risks and other uncertainties associated with project delivery in the customer’s favour.

For example, a ‘traditional’ capital project might involve the client, from their own resources, drawing up detailed specifications for equipment and commissioning a capital goods supplier to construct it under their, or their agent’s, supervision (they might not want to engage in hands-on project management). The project would probably be financed on the client’s balance sheet. The equipment would then be delivered to the client and after a short period of warranty the supplier would withdraw. This is a characteristic that one UK minister refers to, with reference to the construction industry, as the ‘BAD old days’, BAD meaning ‘build and disappear’, (cited in Winch, 2000: 149). In this model, it is usually the client’s responsibility to integrate the equipment with other physical or service features and to maintain and operate the equipment over its lifetime, upgrading and replacing as necessary. The client also remains responsible for the provision of the service to its own customers.

However, there is strong evidence that the demands and expectations of clients are changing as the contexts of their own businesses are being transformed by globalization, their own desire for strategic specialization, changing regulatory environments, new technological possibilities and so on. This forms part of a more general trend towards the outsourcing of activities by many client organizations (Johnston and Lawrence, 1988; Spekman et al., 1994; Harland et al., 2005). From the primary contractor’s viewpoint, these changing requirements are reflected in an increasing desire on the part of their clients to shoulder less of the risk and responsibility for the capital good than they have done historically. For example, the growth in demand for ‘turnkey’ solutions has in particular been noted (Davies, 2003; Galbraith, 2002). In these projects, the customer does none of the interfacing between the different parts of the system, but deals with a single supplier in the provision of the entire system. In other cases, the customer is interested only in the outcome of the capital project, relying on others to build and operate it.

Environment

Morris (1994) has suggested that it was during the 1970s that major projects started to experience problems associated with the external environment. In particular, projects involving nuclear power, oil exploration and transport infrastructure began to run into opposition from environmental and community groups opposed to the project objectives. Morris argues that this realization led to a shift from a focus on the implementation of the project towards the recognition that the context of projects needs to be ‘managed’ as well. One element of managing projects was a need to take into account not only the internal business context in which the project was initiated, delivered and implemented, but also the external environment of the project as manifested by its broader economic, societal and potential environmental impact or effects and the increasing desire to satisfy the ultimate users or consumers.

Not surprisingly, as major projects have become more significant and far-reaching, the number of potential external stakeholders who might perceive a threat or an opportunity in the delivered project have increased. Indeed, managing the range of new stakeholders in such projects is a source of project complexity in itself. For example, the potential for projects to become politicized, as with Heathrow Terminal 5 (Tether and Metcalfe, 2003) or the Oresund Link (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003), means that one element of managing such projects can be a need for sophisticated stakeholder management (Freeman, 1984; Pinto, 1998; Winch, 2004) as part and parcel of the process of managing the project. The need to take account of divergent and multiple viewpoints and interest groups accentuates the complexity of the project management process and creates even more diverse networks of organizations and relationships that need to be managed.

For example, CoPS tend to be heavily influenced by the external environment (Dingle, 1997). Stakeholders include regulators and legislators (e.g., on safety or planning issues) and pressure groups (e.g., community groups, environmentalists, conservationists, local residents and landowners, etc.). This, it is suggested, is because CoPS have the potential to affect many sections of society and the economy. As a result, the interfaces and relational activities within the project tend to multiply, introducing complicated information channels and procedures (Dingle, 1997). Moreover, clients and users are usually heavily involved in CoPS throughout their initiation, design, build, implementation and operation. Together, these relations add further complexity in terms of organization and management problems (Wang and Von Tunzelmann, 2000; Hobday et al., 2000).

Management

Finally, the management process in major projects can itself be seen as a source of complexity. The argument here is that, hitherto, projects have been conducted within relatively stable organizational contexts with a relatively high degree of certainty and little ambiguity. The primary project management process has therefore been one where conventional management control models—set objectives, plan, monitor, evaluate, correct—have underpinned the development of specific tools and techniques for project management. These were aimed at disaggregating tasks to decompose the project into manageable work packages and then scheduling, tracking and taking corrective actions, as appropriate, to ensure project execution to plan (Harpum, 2004; Kerzner, 2006).

However, the conditions under which major projects are increasingly conducted mean that such ‘rational-linear’ models of the management process may no longer be applicable. Maylor et al. (2008) present a grounded model of dynamic and interactive aspects of projects that impact on managerial complexity: the project mission, the project organization, the project delivery, the project stakeholders and the project team. Writers such as Stacey (1996) have referred to the emergence of new forms of management and leadership appropriate to high levels of instability and uncertainty. This aspect is not one that is characteristically explored in the project management literature with its bias towards metaphors based on ‘control’ rather than ‘chaos’. Indeed, it is here, perhaps, more than anywhere else that both our theoretical understanding and the practice of project management is caught in what Morris suggests is a ‘sixties time warp’ (1994). We return to the...