Extremist trend in the broadly understood ecological movement occurred in the second half of the twentieth century. Of course, before that time there had been cases of violent acts committed in the name of natural environment and animal rights protection. They were, however, spontaneous and sporadic actions and did not lead to the creation of lasting organizational forms. The reasons for the emergence of environmental and animal rights extremism (given a general name of “ecological extremism” in this book) seem to be relatively different, although one can point at shared literary inspirations, which treated the issues related to animal and environment protection as one.1

The sources of environmental extremism should be looked for at the beginning of the 1960s. It was then that the existence of a correlation between increasing environmental exploitation and the growth of prosperity was questioned for the first time. Moreover, an awareness of the possibility of an ecological crisis began to disseminate among a larger public (especially in the United States). People began to realize that if this crisis occurs, it will present a threat to all species on earth. The emergence of ecological consciousness quickly resulted in particular actions of preservative nature. Already in the second half of the 1960s consumer movements in the United States started to loudly demand the right to “a physical environment that would correspond to the needs of the human organism and a high quality of life.” Numerous organizations sprang up like mushrooms with the goal to lobby for the natural environment. In spite of the movements’ intense activity, their actions did not bring the expected results. Anyhow, it did not satisfy all members, who more and more often demanded more radical forms of fighting for environmental preservation. As it seems, the turning point in the formation of green extremism was the 1979 Forest Service decision, called RARE II (“Roadless Area Review and Evaluation II”), to allot 36 million acres of forest land for commercial exploitation.2 The decision was a great shock for some environmental activists because it not only demonstrated the lack of ecological consciousness of the agency, but it also showed the weakness of the traditional environmental organizations, which were unable or unwilling to defy it (due to, e.g., their connections with large corporations and governmental agencies, as well as considerable internal bureaucracy). In a burst of general discontent caused by that decision and adverse climate surrounding the “legal environmental organizations” many smaller and larger groups were founded, and their only goal were resolute (and not necessary legal) actions against rampant indifference toward the natural environment. Among those groups, Earth First! and the Earth Liberation Front became later the most famous.

In the case of extremism in fighting for animal rights, giving reasons for its emergence is not that simple, for it is difficult to pinpoint a turning point that could be regarded as the “ideological trigger” of animal rights radicalism. It is probably so because arriving at radicalism was rather of evolutionary, not revolutionary character – it was a consequence of progressively wide-ranging and audacious postulates regarding the broadening of moral horizons so that they would comprise all discriminated groups of beings, including those that are unable to articulate liberation slogans by themselves. The animal rights movement was born in the nineteenth century in England. And in spite of the fact that at the beginning the source of its motivation were not animals but humans – more precisely, their spiritual and moral development3 – this “narrow anthropocentric perspective” was quickly abandoned in favor of full equality in respecting the interests of all animals (both human and nonhuman). This is how in the 1970s the heretofore most radical and at the same time the most conspicuous claim of the contemporary “liberation movement” was formulated – the claim stating that discrimination against a creature only on account of its species is a prejudice as immoral as racism or sexism. It is worth mentioning that contrary to environmental extremism, which was prompted by the awareness of ecosystems being endangered (hence, it may be considered in the categories of species’ struggle for survival), radical movement of animal protection came into being as a result of an altruistic in its nature and autonomous in its progress (although historically determined) development of moral consciousness (aiming at the broadening of the moral community).4 In the second half of the twentieth century this development brought about a real outbreak of radical animal rights groups fighting for a total ban on exploitation and killing of animals. Among those groups, the Animal Liberation Front, the Justice Department, and the Animal Rights Militia became the most prominent ones.

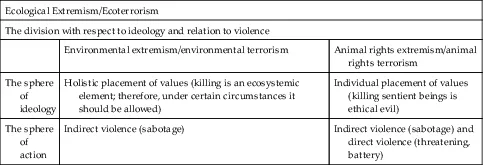

Ecological extremism has not yet been defined in the subject literature. However, it can be defined as having, propagating, and realizing radical environmental or animal rights beliefs. There are, nonetheless, different terms used in the subject literature in regard to extremist activities of the groups fighting for animal rights or natural environment protection. Sean Eagan, for example, refers to both types of groups by interchangeably using three terms: (1) “environmental terrorism,” (2) “eco-terrorism,” and (3) “ecological terrorism,” which he (not entirely consequently5) applies to denote “an environmentally oriented subnational group [acting] for environmental–political reasons” (Eagan, 1996). Whereas other authors (Laquer, White, Liddick, Griset, Mahan), as well as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), use the term “ecoterrorism”6 to describe the activities of radical animal rights and environmental groups.7 Using a common term in relation to the actions of the protectors of the natural environment and animal rights (also known as animal liberationists) may be justified by the fact that many organizations of both types stay in close cooperation because their goals are in many ways convergent. In spite of that concurrence with regard to the goals and similar organizational structure, there are significant tactical and ideological differences between radical animal rights and environmental activists, which preclude their total convergence. This is probably the reason why many researchers (Mullins, Kushner, Bolz, Dudonis, Schulz) distinguish8 between ecoterrorism understood as violence in defense of nature, and animal rights terrorism or animal rights groups terrorism defined as violence in defense of animals (Mullins, 1997; Kushner, 2003; Bolz et al., 2005).

It should be noted that the most important of such “ideological differences” (which at the same time is a criterion for distinguishing between environmental and animal rights extremisms) consists in different placing of values. Animal rights defenders see the value only in individually living and feeling beings, while environment defenders place it in the natural world as a whole. It is noteworthy that this difference has a significant practical importance. For animal liberationists, every animal possesses the inalienable right to live that should be respected by the human being. Environment defenders, on the other hand, permit killing animals by humans if, of course, it serves meeting their living needs (understood more or less broadly) and does not disrupt the ecological balance. The differences between the two types of groups pertain also to the attitude toward violence and the tactic that stems from it. Paradoxically (taking into account the fact that they allow the possibility of killing), environmental groups in their fight for “restoring ecological balance” use almost exclusively indirect violence based on ecological sabotage, whereas animal liberationists, apart from indirect violence, use also, although in a limited scope, direct violence targeted at humans (who as sentient beings do belong to the value universe, but under certain circumstances they can be excluded from it due to their “evil deeds”). (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1

The Division of Extremism and Terrorism with Respect to the Ideology and Relation to Violence

| Ecological Extremism/Ecoterrorism |

| The division with respect to ideology and relation to violence |

| Environmental extremism/environmental terrorism | Animal rights extremism/animal rights terrorism |

| The sphere of ideology | Holistic placement of values (killing is an ecosystemic element; therefore, under certain circumstances it should be allowed) | Individual placement of values (killing sentient beings is ethical evil) |

| The sphere of action | Indirect violence (sabotage) | Indirect violence (sabotage) and direct violence (threatening, battery) |

Source: Own elaboration.

Not all authors who write about radical animal rights and environmental groups are willing to use the term “terrorism” to describe their actions. Gus Martin, for example, qualifies the activities of both types of groups as “leftist single-issue extremism” (Martin, 2003a). Christopher C. Harmon also has serious doubts with regard to the sense of using the term “terrorism” in relation to radical animal rights and environmental groups. He believes that activists motivated by animal rights and environmental issues do not possess the inclination to carry out actions that are usually described by that term. The very character of their activities may be taken as an evidence for that – they do not aim at destruction of democratic order, nor do they support killing or any other forms of battery. Although they do cause fright by destroying property, their goal is not to arouse mass fear but to bring about the “disruption of actions” of certain classes of people (foresters, lumberjacks, entrepreneurs) and that way to induce a change in the politics of the government (Harmon, 2000). A similar opinion was expressed by Leonard Weinberg and Paul Davis, according to whom “an act of terrorism is not, as is sometimes believed, the same as ...the sabotage of public or private property” (Weinberg and Davis, 1996; Eagan, 1996). Bron Taylor also points at the inadequacy of the term “terrorism” in relation to the actions of radical animal rights and environmental movements. In his opinion, “despite the frequent use of revolutionary and martial rhetoric by participants of these movements, they have not, as yet, intended to inflict great bodily harm or death” (Taylor, 1998). Of course, the ones who protest the loudest against using the term “terrorism” are the activists of ecological groups. They believe that using this term to characterize actions not aiming at natural beings but at the unanimated ones, which are harmful to the former ones, is an abuse that stems from the anthropologically oriented moral perspective. This mindset creates the wrong perception of violence and terrorism, that is, as something that may occur only in reference to humans and their property and not as pertinent to other nonhuman beings. In the opinion of environmental and animal rights radicals, the rejection of anthropocentrism must necessarily lead to accepting that the “real terrorists” are not those who protect the “oppressed and persecuted beings” (nature and animals) but those who benefit from their “exploitation” (Best, 2004).

Obviously, the discussion on whether something is or is not terrorism may be reasonably led only based on clearly established criteria of that phenomenon or on a well-constructed definition.9 The problem is, there are many such criteria and definitions10 and there is no consensus (both in the academic and political circles) as to which of them could be regarded as commonly accepted. A way to tide over this definitional and terminological impasse is to call for statistical analysis to itemize the most frequent elements in dozens of existing definitions. In their book Political Terrorism, Alex Schmidt and Albert Jongman developed such statistics on the basis of 109 most often accepted terrorism definitions. The components that occurred consistently, as it transpired, in over 50% of definitions were: violence (83.5% of definitions), political character of the phenomenon (65% of definitions), and fear (51% of definitions) (Schmidt, 1988).

Will we find all those elements in the ecological radicals’ actions? An attempt to answer that question is not as simple as it may seem. (It necessarily depends on various worldview judgments, with which one approaches the activity of the animal rights and environmental movements). Among the aforementioned elements only the adjective “political” seems not to raise any doubts or controversies. It is a fact that the ecological radicals’ actions can be understood only in the context of the political goals they strive for. However, it is worth mentioning that these goals are not always deep ...