eBook - ePub

A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching

Translating the Evidence-Based Model Teaching Criteria

Aaron S. Richmond, Regan A. R. Gurung, Guy Boysen

This is a test

- 70 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching

Translating the Evidence-Based Model Teaching Criteria

Aaron S. Richmond, Regan A. R. Gurung, Guy Boysen

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

This pithy yet thorough book provides an evidence-based guide on how to prepare for online teaching, especially for those who are making a swift transition from face-to-face to online instruction.

Guided by the Model Teaching Characteristics created by The Society for the Teaching of Psychology, this book covers important topics like: how to adapt to expected and unexpected changes in teaching, how to evaluate yourself and your peers, and tips on working smarter/optimizing working practices with the resources available. The features of the book include:

-

- Practical examples exploring how to solve the typical problems of designing and instructing online courses.

-

- Interactive "Worked Examples" and "Working Smarter" callouts throughout the book which offer practical demonstrations to help teachers learn new skills.

-

- Further reading and resources to build on knowledge about online education.

-

- End of chapter checklists which summarizes suggestions about how to be a model online teacher.

This essential resource will provide support for teachers of all levels and disciplines, from novice to the most experienced, during the transition to online teaching.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching di Aaron S. Richmond, Regan A. R. Gurung, Guy Boysen in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Education e Education Theory & Practice. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1

Apples and Oranges, But Still Fruit

Model Teaching Universals and Differences

Confessions of Three Skeptical Teachers

At some point, each of the authors of this book had the same thought: “There is no way I am going to teach online.” Regan remembers the first time he was asked to teach online. As a passionate teacher who enjoyed teaching large introductory classes of 300 students, as well as advanced classes of 25, he could not imagine teaching online. Why? He had preconceptions about what it would be like and could not imagine teaching without seeing his students live, face to face, numerous times a week. Guy too believed that technology would interfere with, rather than augment, what made him an effective teacher, and Aaron struggled with the thought that the rapport he had with his students would be somehow be lost online. That was then—now, we are converts.

Today, all three of us are firm believers in the merit of online teaching. While you would hope the authors of a book on online teaching support the practice, writing this book is not what changed our minds. First, we have examined the research. The evidence for the efficacy of online teaching is astounding and the benefits of a well-designed course are impossible to ignore. Second, from our years of personal experience, we have seen firsthand how a well-designed online course can lead to significant learning and, in many cases, provide some students with a better experience than they would have had in person. Of course, you will notice the caveat in each of those statements—“well-designed.”

In this book we will provide you with the key ways to create and implement a well-designed online class. For many years we have immersed ourselves in defining, researching, and promoting the practices that define excellent teachers. In our own training to teach online we have taken advantage of the multiple resources about online teaching. There is a wealth of books, blogs, teaching center webpages, and even certified workshops on how to effectively teach online. Organizing all of this information so that it can benefit other teachers is challenging, but we have a way.

We bring you something different. Using the Model Teaching Criteria framework (Richmond et al., 2016), which is a set of six core principles characterizing model college and university teachers, we have synthesized the diverse guides and evidence-informed practices regarding online teaching. In this book, we offer a concise outline of the practices that will make you a model online teacher. Before discussing model online teaching, we introduce the general Model Teaching Criteria and the training needed to be a model teacher.

The Background of Model Teaching

If you are reading this book and starting at this chapter instead of jumping right ahead to the instructional tips, you want to be a good teacher—maybe even a great teacher. Definitions of great teaching exist, but college teachers rarely receive sufficient guidance for reaching such pinnacles (see Gurung et al., 2018, for a full review). Unlike K–12 education, college teachers typically do not receive pedagogical training, and this can make it a challenge to know where to begin as a teacher, let alone how to be great. We have had many conversations with graduate students who progressed from teaching assistants to instructors of record without training. Then, when those graduate students become faculty members, an advanced degree served as the only required evidence that they were ready to teach college courses full time for the next several decades. The assumption seems to be that if teachers possess knowledge, they should intuitively know how to pour it directly into the minds of students.

Of course, pouring content from your head into the minds of students is not the definition of good teaching. But what is? Behavior is complex, and it always influenced by multiple factors. Likewise, good teaching is comprised of multiple components. A few years ago, the three of us dove into the rich literature on teaching and pulled as many of these components together as we could. We built on the strong work of others: For two years, we worked with a committee of the Society for the Teaching of Psychology to establish the basic features of good college teaching. The committee studied what it meant to be a model teacher and concluded that there are six general criteria for model teaching (Richmond et al., 2014). This work led to checklist of model teaching practices that the three of us then revised and expanded into the Model Teaching Criteria (MTC, Richmond et al., 2016).

Before we unpack the criteria and illustrate how they can be useful in your progress toward online greatness, we need to discuss the sources of our teaching suggestions. You may be familiar with the terms “best practices” and “evidence-based,” but they are slightly misleading. Classes vary in modality, size, composition, discipline, level, and college setting. There can be no “best” practice that works equally well in every context. We prefer the term “better.” Similarly, “evidence-based” is not always possible. As three experienced pedagogical researchers, we can tell you that most prescriptions for good teaching in higher education are not (and cannot be) directly tested. There are too many variables to control, and classrooms experiments pose practical and ethical challenges. Learning is complex and research on education is imperfect, so we cannot claim that every suggestion in this book is evidence-based, and we feel it is false advertising to do so. We prefer the term “evidence-informed.” In this book, we try to provide you with suggestions for better online teaching based on evidence-informed practices.

The sources of evidence for better teaching practices come from the many different groups working on understanding how learning works. Depending on discipline and training, your exposure to these areas will vary. When the three of us want to get up to date on teaching research, we first go to the major pedagogical journals in our home discipline of psychology: Teaching of Psychology, Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, and Psychology of Learning and Teaching. All three journals publish research on the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL), which is commonly described as “the theoretical underpinnings of how we learn, the intentional, systematic, modifications of pedagogy, and assessments of resulting changes in learning” (Gurung & Landrum, 2015, p. 1). When SoTL is limited to and explicitly designed for specific disciplines, it is sometimes referred to as Disciplinary Based Educational Research (DBER). Nearly every academic discipline does SoTL, and this literature is the source of many evidence-informed teaching practices (Chickering & Gamson, 1987; Persellin & Daniels, 2014).

In addition to SoTL, researchers in the disciplines of education, educational psychology, and cognitive psychology also study learning, and scholars from a variety of disciplines consider their work part of the broader field of learning science (Benassi et al., 2014; Bransford et al., 1999). As if these varied sources of pedagogical knowledge were not enough, a separate body of research exclusively focuses on online teaching and learning, which is a topic largely skirted in the previously mentioned areas. Instructional designers, mainstays of academic technology departments and online campuses, have contributed a wealth of knowledge to inform online teaching practices (Dick et al., 2015; Smith & Ragan, 2005; Spector et al., 2015).

In our review of existing guides for online teaching, we note that most pull nicely from SoTL, DBER, learning sciences, and instructional design (e.g., Darby & Lang, 2019; Linder & Hayes, 2018; McCabe & Gonzales-Flores, 2017; Nilson & Goodson, 2018; Riggs, 2019; Stein & Wanstreet, 2017). Many of these guides resemble classic books about teaching, such as Tools for Teaching (Davis, 2009) and Teaching Tips (McKeachie & Svinicki, 2012). What they all have in common is that they outline specific teaching techniques, not an overarching model of what constitutes good teaching. We take a different tack and provide an interconnected structure of characteristics that together make a model teacher. You will find lots of teaching tips and tools in this book, but we present them as just pieces in a larger framework of model teaching.

What is Model Teaching?

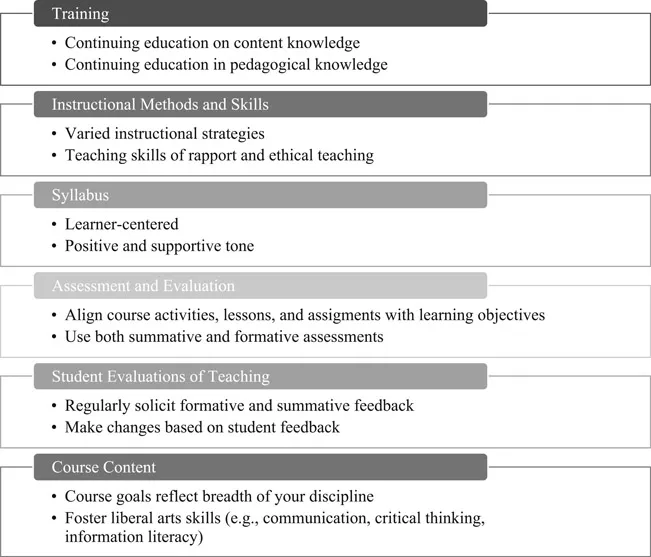

In our view, and informed by the evidence, model teaching involves training, instructional methods, course content, syllabus design, assessment, and student evaluations. You will see these six criteria interwoven throughout this book, but we offer a brief overview of them here (see Richmond et al., 2016 for all the glorious details). Figure 1.1 summarizes the key components of this model.

Figure 1.1 A List of Model Teaching Criteria and Subcriteria (Richmond et al., 2014, 2016)

Model teachers are well-trained experts. At the most basic level, model teachers are credible authorities in their discipline. Teachers are most effective when they teach subjects that they have mastered. Achieving mastery requires up-to-date, specialized knowledge in that subject area (Boysen et al., 2015). As such, after earning their advanced degrees, model teachers demonstrate expertise through continued education and scholarship. Just like face-to-face teachers, online teachers must also follow these training guidelines.

In addition to their discipline-specific expertise, model teachers possess pedagogical expertise. Some graduate students have been part of training programs such as Preparing Future Faculty or department training as part of being a teaching assistant. Faculty may occasionally attend professional development sessions about teaching and learning offered at their college, or they may read about teaching trends in the Chronicle for Higher Education or Inside Higher Education. These types of ad hoc training are not enough. Model teachers learn about teaching through self-directed professional development, but they also receive formal training. There is no substitute for attending a course on pedagogy. Whether it is an online workshop, a multiday conference, or a full academic course, such training is essential for model teachers to establish and maintain expertise on pedagogical theory and practice.

As a result of their training, model teachers follow fundamental practices in the design, instruction, and improvement of their courses—these are the other five components of model teaching. The purpose of this book is to outline these model teaching practices as their relate to the context of online instruction. As can be expected, most of the subcriteria that made up the original Model Teaching Criteria (Richmond et al., 2016) are directly or indirectly applicable to online teaching. In following chapters, we explicitly use the model teaching framework to help you learn about online teaching.

Model teachers use learner-centered principles to design their syllabi (see Chapters 2 and 3). Their syllabi communicate to students who they are as a teacher, define the relationship between the students and the teacher, provide a permanent record for future use, and serve as a cognitive map and learning tool for the course (Richmond et al., 2016). Model teachers’ syllabi are transparent and complete. They have detailed policies on grading, academic misconduct, attendance, plagiarism, etc., to communicate expectations to students.

Model teachers intentionally select course content (see Chapter 2). Whenever relevant, they align content to disciplinary guidelines about essential learning goals. Model teachers also go beyond their disciplines. They help students develop liberal arts skills related to communication, critical thinking, and collaboration.

Model teachers use varied instructional methods (see Chapter 4). It is clear from even a quick look at various teaching tips books (e.g., Davis, 2009) that there are a variety of ways to teach. Online teaching can utilize a wealth of instructional methods that go beyond posting lecture slides, asking questions, and then giving a test. Some of the better, evidence-informed methods include collaborative learning, problem-based learning, and just-in-time-teaching, all of which require active student engagement. Developed primarily in the context of face-to-face learning, each of these techniques can also be adapted to online learning. When implementing these methods, model teachers exhibit skills such as student-teacher rapport, active listening, and technological competence.

Model teachers are engaged in the process of assessing student learning (see Chapter 5). They write learning objectives to guide instruction, assess student achievement of those objectives, reflect on the outcomes, and revise instruc...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Boxes

- Preface

- 1 Apples and Oranges, But Still Fruit: Model Teaching Universals and Differences

- 2 Student Interaction With Content

- 3 Student-to-Student Interaction

- 4 Instructor-to-Student Interaction

- 5 Online Assessment

- References

- Index

Stili delle citazioni per A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching

APA 6 Citation

Richmond, A., Gurung, R., & Boysen, G. (2021). A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching (1st ed.). Taylor and Francis. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2096446/a-pocket-guide-to-online-teaching-translating-the-evidencebased-model-teaching-criteria-pdf (Original work published 2021)

Chicago Citation

Richmond, Aaron, Regan Gurung, and Guy Boysen. (2021) 2021. A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis. https://www.perlego.com/book/2096446/a-pocket-guide-to-online-teaching-translating-the-evidencebased-model-teaching-criteria-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Richmond, A., Gurung, R. and Boysen, G. (2021) A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching. 1st edn. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/2096446/a-pocket-guide-to-online-teaching-translating-the-evidencebased-model-teaching-criteria-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Richmond, Aaron, Regan Gurung, and Guy Boysen. A Pocket Guide to Online Teaching. 1st ed. Taylor and Francis, 2021. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.