eBook - ePub

The South Downs

Peter Brandon

This is a test

- 280 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

The South Downs

Peter Brandon

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The South Downs has throughout history been a focus of English popular culture. With chalkland, their river valleys and scarp-foot the Downs have been shaped for over millennia by successive generations of farmers, ranging from Europe's oldest inhabitants right up until the 21st century. '... possibly the most important book to have been written on the South Downs in the last half-century... The South Downs have found their perfect biographer.' Downs Country

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

The South Downs è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a The South Downs di Peter Brandon in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Storia e Storia britannica. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Chapter One

THE CHARACTER OF THE DOWNS

To take to the road with the aim of keeping Hilaire Belloc’s ‘great hills of the south country’ in sight westwards from their spectacular white cliffs of Beachy Head until their majestic sweep comes to an end, means a journey of more than eighty miles well into Hampshire. An observant traveller may well feel in a kind of limbo when the formidable north-facing escarpment of the Downs, the most imposing sight in southern England, finally peters out. True, the same unvarying dry, flinty chalkland continues on towards the great chalk table land focused on Salisbury plain, but it becomes low, broken and indeterminate. It is round about Old Winchester Hill (12 miles east of Winchester), where the skylark sings above the most dramatic situation of the Iron-Age hillforts, that one becomes aware that the landscape has a different ‘feel’. So it is about here that the South Downs may be reckoned to end (or have their beginning).

This is the definition of the South Downs adopted for the purpose of this book. It is broadly comparable with that of two government quangos, the Countryside Commission and English Nature (though both extend the Downs to Winchester itself). It is also approximately coincident with the bounds of the Ministry of Agriculture’s South Downs Environmentally Sensitive Area Scheme which pays farmers for maintaining or adopting agricultural methods which promote the Downs’ conservation and enhancement.

This modern definition fits our age of the motor car and the new sciences of landscape analysis. When travel was slower and more arduous, the local background to people’s lives was much more restricted, and many local differences, now blurred, were formerly more marked. A farmer’s or parson’s notion of the South Downs was then more limited. In 1800, and before, as for a considerable period afterwards, the South Downs were associated in people’s minds with their most renowned product, the celebrated breed of Southdown sheep which, improved by John Ellman of Glynde and others, became the progenitor of all the other English down breeds and had a powerful influence on sheep farming worldwide. Originally, this native breed did not graze the whole extent of the range now called the South Downs but was confined to the eastern stretch of the Downs between Beachy Head and the Adur valley. In their minds’ eye the old farmers identified the South Downs with stark, bare downs open to the sky and rolling down to sea cliffs. They knew them as endless miles of old chalk grassland, feeding immense flocks, bordered by cornland at lower levels, made productive by the sheep’s dung. Farmers of more than two thousand years earlier would have recognised this same austere landscape with its plough-oxen and shepherds. The 18th- and 19th-century downland farmers in these Eastern Downs thought of the wooded Western Downs beyond the Adur river, as if it were another country (which in several respects it still is). This landscape of the Eastern Downs has almost totally vanished since the second World War, though people over the age of 60 years wistfully recall the life, sounds and scents of its immemorial past as familiarly as does the modern child the present great blocks of wheat, superstores and country parks.

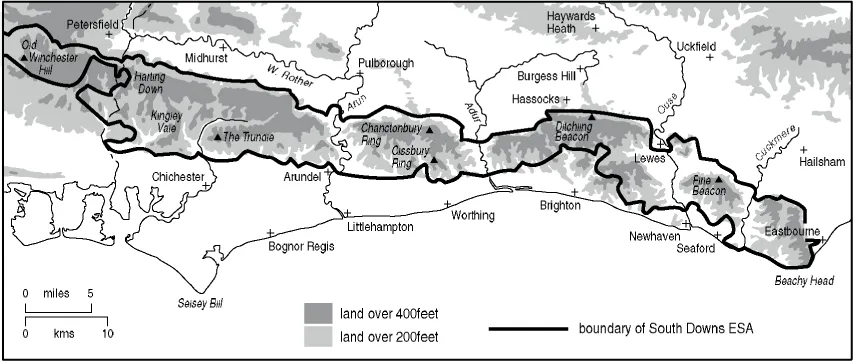

2 The South Downs Environmentally Sensitive Area. Note its extreme vulnerability to urban encroachment in the Brighton area and in the hinterland of Portsmouth.

This 18th-century idea of the South Downs is confirmed by the parson-naturalist Gilbert White who described his native village and the Downs with such charm and affection in his Natural History of Selborne (1798).1 He recorded that the Sussex Downs ‘is called the South Downs, properly speaking, only around Lewes’. He also observed the two distinctly different breeds of sheep divided by the river Adur, each adapted to its different terrain which had evidently been long lasting. The contemporary agricultural writers, Arthur Young and William Marshall, adopted the same customary use of the name ‘South Downs’2 but it was not only people with farming interests who accepted these limits. Dr. Gideon Mantell, the pioneer geologist of the South Downs, explained in his The Fossils of the South Downs (1822) that his book was originally intended to comprehend only the eastern part of the Sussex Downs as far as the Adur valley ‘which constitutes the western boundary of the South Downs’. Later 19th-century writers adhered to the same usage, the famous archaeologist Lane Fox (who later adopted the name Pitt Rivers) noting the limited usage of the name South Downs as late as 1868 when he wrote his pioneer essay on the archaeology of the Downs.3

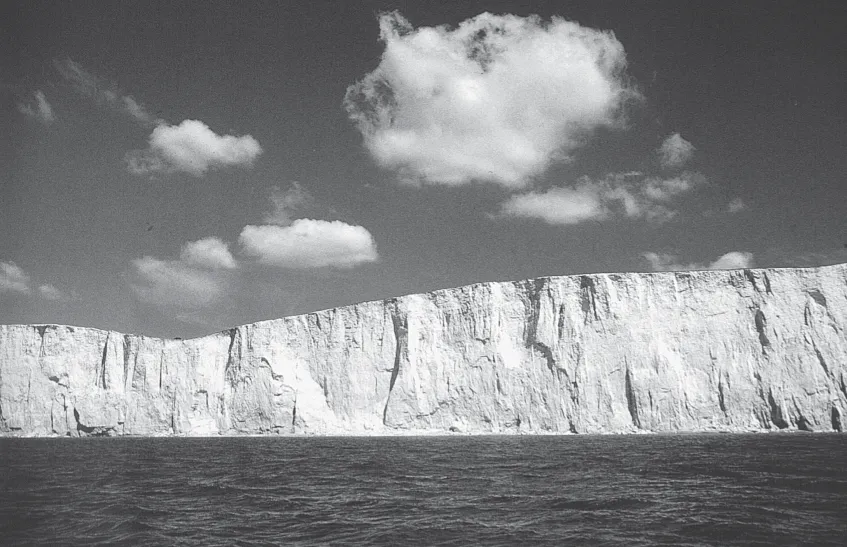

3 The chalk cliffs at the Seven Sisters.

It was not until the late 19th century that the public began to think of the South Downs as extending right across Sussex to the county border with Hampshire. W.H. Hudson in his classic Nature in Downland (1900)4 observed this change in the perception of the South Downs and noted that general use then had it that the name then comprehended the whole range of the chalk hills in Sussex. This recognition of the physical and cultural integrity of the larger area is presumably due to more general travel by railway which had the effect of blurring original differences in dialect, folklore and farming and made feeling for landscape less local. The new fashion for historical and descriptive writing on a county basis also contributed to the changed view.

It is only in recent years that writers have chafed at county boundaries and treated the South Downs from a geographical and ecological point of view, so extending the definition to cover the continuation of the Downs into Hampshire. Thus the South Downs may now be said to have three component parts, the Eastern Downs, the Western Downs and the East Hampshire Downs, together with the river valleys which cut across them and the land immediately below them (the scarpfoot). The scenic and cultural heritage of the blocks of downland varies one from another in several respects, and each has its admirers, but it is the primordial shapes and ancient presences of rounded hills such as Mount Caburn, Firle Beacon and Windover Hill and the toy villages and half-hidden little country churches of the Eastern Downs that came to be regarded as the epitome of the South Downs and the most beautiful of all the English chalk country. It is this section of the South Downs that acquired worldwide fame with Kipling’s verses which seeped so deeply into the mind as to bring tears to the eyes of exiles who longed for home. It is significant that the most recently published book on the South Downs, Michael George’s The South Downs (1992), celebrates in photography not the whole range of the chalk hills but the special feeling engendered by the ‘White Cliff Country’ where the Downs meet the sea and add ‘their magnificent white cliffs to the outline of England’.

Few lines of hills have caught the public imagination for generations as has the steep northward-facing escarpment of the Downs, whether rising smooth-shaven abruptly from the flat Weald, ‘so noble and so bare’ in Belloc’s felicitous phrase or mantled with hanging woods. This virtually unbroken steep wall forms the horizon for hundreds of thousands of inhabitants in southern England and has remained unchanged for centuries. Those who know the Dorset or the Berkshire Downs are unprepared for its formidableness and grandeur. For the people of the Surrey and Sussex Wealds this great wall is the familiar backdrop to their daily lives. They feel more comfortable having it there, unspoilt, a reassuring image of home which greets them on return. Persons who have loved that view, but are now too infirm to visit it, value it as profoundly for simply being there. It is reckoned that views including the distinct skyline of the South Downs increase the sale value of almost every country dwelling—even if binoculars are needed actually to identify them! With the knowledge that beyond the Downs is sea, the crest has also been a constant source of fascination and inspiration, a boundary between the seen and the unseen, which to William Anderson of Clayton near Ditchling signified a point of departure for imagination and invention.5 It has been spared from building in past times by the depth of wells needed and more recently by the determination of landowners, planners and amenity societies to preserve it inviolate, so that hardly a building breaks the smoothness of the skyline. Only national authorities have outraged it. A ‘supergrid’ of electricity pylons from the now vanished power station at Shoreham Harbour strides over the Downs with the insensitivity of the mechanistic Martians in H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds, blundering over the skyline, as at Fulking north of Hove, and crashing through valleys and spurs instead of following the lines of the land more naturally as on the West Dean estate. The same sense of reverence due to the Downs is lacking in those now erecting a rash of telecommunication masts.

4 An aerial view of the line of the escarpment, looking westward from Mount Harry near Lewes.

Alec Clifton-Taylor, in a memorable television broadcast on Lewes,6 was asked where he would most like to live. He replied, without hesitation, ‘two miles north of the Downs, looking at them’. It is evident that the affluent have had the same preference certainly for some two thousand years, witness a long line of Roman villas, including Bignor, and country houses, mostly of Elizabethan or earlier origin, which lie in the calm beauty under the northern edge of the Downs, neither too close nor too far away, which fulfilled all the requirements to enjoy the special character of downland country. Passing from west to east the great houses and estates included Lavington (now Seaford College), Burton Park (until recently a girls’ school), Cowdray, now a ruin, but once the greatest of all, Pitshill, Parham, Wiston, Danny, Streat Place, Glynde Place, Firle Place, Wootton and Folkington Manors. It was much more convenient and much more amenable for grandees to farm the rich soil below the Downs and run great flocks of sheep on the downland itself rather than to live there, for the Downs can be bleak in the winter. This is probably the reason why the once numerous country houses in the Downs themselves have not lasted as long as those at the Downs’ foot, e.g. Halnaker, a ruined medieval mansion, Michelgrove, Muntham Court at Findon and Hangleton Manor near Brighton.

It is to the way the Downs stand in marked contrast to the Weald and the sea, and not because of their height, that their impressiveness is due. As W.H. Hudson observed, the pleasure in looking over a wide prospect does not depend on the height above, because whether the height be 500 or 5,000 feet, we experience much the same sense of freedom, triumph and elation in an unobstructed view all around.7 H.G. Wells, who spent part of his boyhood at Uppark, has expressed the effect of this matter of height differently but with the same meaning: ‘It is after all not so great a country this Sussex, nor so hilly. From the deepest valley to highest crest is not 600 feet. Yet what greatness of effect it can achieve. There is something in these downland views, which like sea views, lifts a mind out to the skies.’8

As one explores the Downs, one also comes to the realisation that the downland can impinge on the senses on a scale that feels more vast than the actual extent, for this, too, is only relative, and has nothing to do with the actual size of the country. The range of the human eye is only about twenty miles and seeing that distance conveys the same exhilaration as would be experienced on the Russian Steppes. Thus seeing the horizon all around one, or at least in an arc or a semicircle, as is the arrangement of the hills in southern England, induces a notable feeling of expansiveness. The uneven lie of the land in the Weald sharpens this impression, for, standing on one of the many vantage points on the crest of the Downs, we see the horizon sinking below eye level. This seems to make the sky the inner side of a sphere enclosing the earth, and this increases immensely the sense of the apparent distance.

Thus with their considerable elevation, their abrupt rising and dipping, and with deep, ravine-like valleys cleaving into the escarpment, the Downs feel more nearly true mountainous country than other chalklands and, in views across the Weald towards Blackdown, Hindhead, Leith Hill and the rampart of the North Downs closing the horizon, one can savour something of the solemn grandeur and sublimity which was the ‘sort of delectable mountain feeling’ which tranquillised Bishop Wilberforce at East Lavington, near Duncton Hill.9 In certain light, as when the Downs disappear mysteriously into cloud or mist, or silhouetted against the setting sun, this feeling is reinforced and it recalls Gilbert White’s description of the Downs as a ‘majestic chain of mountains’.10 Even in reality some of the downland slopes are steeper than those of some mountains. It is a stiffer climb, for example, up Kingston Hill, near Lewes, than over parts of the Mourne Mountains in Ireland—and the air is as keen.

5 This ruined terrace is almost all that remains of Muntham Court near Worthing.

The Eastern Downs

The absence of trees or hedges bestows a striking individuality on the shape and form of the land because chalk, whether grazed or cultivated, retains an impressive and monumental simplicity wherever gently curving lines are not masked by woodland or engulfing scrub which makes the form of the hills scarcely discernible. The peculiar smoothness and bareness results from centuries of shaving by sheep and plough (villages and farmsteads being visible only in hollows). This has given rise to broad, bare, round and smooth sensuous outlines of hills which have long appealed as the shape of the human figure. W.H. Hudson likened them to ‘the solemn slope of mighty limbs asleep’,11 F.W. Bourdillon saw them as ‘softly rounded as a mother’s arm about a cradle’. I...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Colour plates

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Character of the Downs

- 2 The Chalk Takes Care of All

- 3 Early Man

- 4 The Saxon South Downs

- 5 Farming Communities in the Middle Ages (1100-1500)

- 6 The Saxon and Early Medieval Downland Church

- 7 Sowing the Seeds of Change: the 16th and 17th Centuries

- 8 The ‘New Farming’ (c.1780-1880)

- 9 Traditional Farm Buildings and Rural Life (c.1780-c.1880)

- 10 Nature, Man and Beast

- 11 The Making of an Icon

- 12 The Downs that were England (1900-1939)

- 13 The Call to Arms

- 14 After Eden

- 15 Places and Ideas: The Downs in Literature and Painting

- 16 The Austere Present

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- References