eBook - ePub

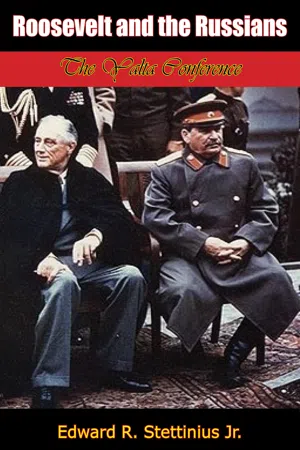

Roosevelt and the Russians

The Yalta Conference

Edward R. Stettinius Jr.

This is a test

- 239 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Roosevelt and the Russians

The Yalta Conference

Edward R. Stettinius Jr.

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Ever since the Big Three—Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin—had their historic meeting in the Crimea, controversy has raged about the decisions, concessions, and agreements which took place there. It is important, in the light of subsequent world history, to know what really happened at Yalta. Now, for the first time, the entire story of those seven days in the history of the world—February 4-11, 1945—is brilliantly revealed by Edward R. Stettinius who, as Secretary of State, sat in on all the meetings that took place, and who, since the deaths of Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins, is perhaps the only man who can tell all that happened at Yalta.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Roosevelt and the Russians è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Roosevelt and the Russians di Edward R. Stettinius Jr. in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Storia e Storia militare e marittima. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

StoriaCategoria

Storia militare e marittimaPART ONE—TRYING TO BUILD A BETTER WORLD

CHAPTER 1—Background of the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference—February 4–11, 1945—was the most important wartime meeting of the leaders of Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the United States. It was not only the longest meeting of President Roosevelt with Prime Minister Churchill and Marshal Stalin; it was also the first time that the three leaders reached fundamental agreements on post-war problems as distinct from mere statements of aims and purposes. Many problems of a non-military nature had been discussed at Teheran, but basic agreements were not reached or even attempted.

This was the second time the three war leaders had met, but it was the first occasion on which they had met with all their foreign ministers. Although Anthony Eden and V. M. Molotov had participated in the Teheran Conference—November 28–December 1, 1943—Cordell Hull had not.

The Yalta Conference, too, was the first real occasion on which the Chiefs of Staff of the three countries conducted an exhaustive examination of the respective military positions of the Allied forces and discussed in detail their future plans. The timing of the second front and related military questions had been discussed at Teheran, but it was not until Yalta that sufficient confidence existed among the three nations for a free and open examination of future operational plans.

Thus the Yalta Conference marked the high tide of British, Russian, and American co-operation on the war and on the post-war settlement. In the days immediately after the Conference most American newspapers gave high praise to what had been accomplished in the Crimea.

On February 13, 1945, the New York Times wrote:

The long and detailed agreements announced at the end of the second conference between President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Marshal Stalin and now submitted to the judgment of the world are so broad and sweeping that it will take a detailed analysis and a demonstration of their application in actual practice to measure their full scope and final implications. But even the first glance gives assurance that, though they may disappoint some individual expectations, they justify and surpass most of the hopes placed on this fateful meeting, and in their aims and purposes they show the way to an early victory in Europe, to a secure peace, and to a brighter world....

The alliance of the Big Three stands firm. Progress has been made. The hope of further gains is high. This conference marks a milestone on the road to victory and peace.

The New York Herald Tribune called the Yalta communiqué a “remarkable document.” “The overriding fact,” this paper observed, “is that the conference has produced another great proof of allied unity, strength and power of decision.” The Philadelphia Record termed the Conference the “greatest United Nations victory of this war.”

Congressional leaders like Senators Barkley, Vandenberg, White, Kilgore, and Connally praised the results of the meeting. A survey of public reaction, conducted for the State Department during the last week of February, revealed that the American people considered the Yalta Conference a success. This survey reported that the Conference had raised hopes for a long-time peace; it had increased satisfaction with the way the Big Three were co-operating, and with the way the President and the State Department were handling American interests abroad.

Although the public reaction to the Yalta communiqué was overwhelmingly favorable, there was a critical minority who singled out a variety of aspects for attack. The voting formula in the Security Council was challenged by some on the basis that the Great Power veto left the proposed world organization without sufficient power. Some bitterly attacked the communiqué for failing to spell out what was involved in the unconditional surrender of Germany. The greater portion of the minority criticism centered on the Polish boundary arrangement and on the new agreement on the Polish Government. In spite of all these attacks, the overall reaction of the country was favorable to the solution of the Polish—as well as to the other—questions.

Three years after the meeting in the Crimea, however, the Yalta Conference was under bitter attack. “High Tide of Appeasement Was Reached at the Yalta Conference...,” Life declared in its caption to a picture of the Conference. In the same issue of September 6, 1948, William C. Bullitt charged:

At Yalta in the Crimea, on Feb. 4, 1945, the Soviet dictator welcomed the weary President. Roosevelt, indeed, was more than tired. He was ill. Little was left of the physical and mental vigor that had been his when he entered the White House in 1933. Frequently he had difficulty in formulating his thoughts, and greater difficulty in expressing them consecutively. But he still held to his determination to appease Stalin.

Many more bitter statements have been made in recent criticism of the Yalta Conference. Some of them have been based on misunderstanding, others on prejudice. The following pages of this book reveal how unjust they are. The Yalta record, in spite of these attacks, reveals that the Soviet Union made more concessions to the United States and Great Britain than were made to the Soviet Union by either the United States or Great Britain. On certain issues, of course, each of the three Great Powers modified its original position in order to reach agreement. Although it is sometimes alleged that there is something evil in compromise, actually, of course, compromise is necessary for progress as any sensible man knows. Compromise, when reached honorably and in a spirit of honesty by all concerned, is the only fair and rational way of reaching a reasonable agreement between two differing points of view. We should not be led by our dislike and rightful rejection of appeasement in the Munich sense into an irrational and untenable refusal to compromise.

The attacks on the Yalta Conference, excluding those which are motivated by a blind hatred of Franklin D. Roosevelt, really result from bitter disappointment over subsequent failures to carry out the agreements reached at Yalta rather than over the agreements themselves.

The Yalta Conference was the culmination, in many respects, of long and patient efforts, dating back to President Roosevelt’s first term, to find some basis for a new international understanding with Russia. It was not until eight years after diplomatic relations had been restored, and after the Soviet Union had been attacked by Germany on June 22, 1941, that important steps toward effective co-operation took place between the two nations.

Although some American isolationists tried to bar Lend-Lease appropriations for the Soviet Union, Congress affirmed such aid in October by a strong majority. As Walter Lippmann wisely remarked, the United States and the Soviet Union were “separated by an ideological gulf and joined by the bridge of national interest.”

It is a human frailty to forget too soon the circumstances of past events, and the American people should remember that they were on the brink of disaster in 1942. If the Soviet Union had failed to hold on its front, the Germans would have been in a position to conquer Great Britain. They would have been able to overrun Africa, too, and in this event they could have established a foothold in Latin America. This impending danger was constantly in President Roosevelt’s mind.

Lend-Lease proved to be a powerful cementing force between the two nations. During 1942 the Soviet Union and the United States were just beginning to learn to work together as allies. We did not receive from the Soviet Union the detailed information about its army or about economic conditions within the country which we expected from other Lend-Lease countries. Nor, it must be said, did we give the Russians as much information as the British, for example, received from us. Although this policy has since been criticized, such complete pooling of secret information as took place between the British and the United States was hardly possible in the face of the history of our relations with Russia in the preceding twenty-five years.

The exigencies of war also brought about somewhat closer collaboration between the Soviet Union and the United States. In June 1942, President Roosevelt, Secretary Hull, and Foreign Minister Molotov discussed in Washington not only co-operation in the war, but also the question of maintaining peace, freedom, and security after the war. President Roosevelt told me that Molotov was cold and restrained during the early portion of his visit, but that before his departure he had become friendlier and more cooperative.

Either through diplomatic channels or at the Teheran Conference, Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin had already raised most of the questions that were to be discussed at Yalta. At Teheran, although no agreements had been reached, the three leaders had discussed in a preliminary way such problems as the treatment of Germany, the future of Poland, General de Gaulle and France, Russian participation in the Far Eastern war, a warm-water port for the Soviet Union, colonial empires, Turkey’s entrance into the war, and the founding of an organization of nations.

Actual progress on these and related issues did not occur, however, until Yalta, when a high degree of frankness and co-operation developed among Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin. Although Anglo-American co-operation had developed to a noteworthy degree during the war, diplomatic relations of the two Western powers with the Soviet Union had been far from satisfactory most of the time. Russian disappointment over the unavoidable delay in opening a second front across the Channel was undoubtedly real, and even at the end of 1944 some highly placed Russians were still suspicious of both British and American motives in regard to the future of liberated Europe. All three powers faced, in the months before Yalta, not only the need to push forward plans for a world organization, but a more immediate and urgent need to reach decisions which could be applied as soon as the fighting ended.

As early as 1941 some of the Russian demands in the Balkans and elsewhere were known to us. Shortly after June 22, 1941, Anthony Eden had gone to Moscow to determine what aid the Soviet Union wanted. At this time, even though the Russian armies were in retreat, Stalin indicated that he was less interested in military assistance than in a political alliance and in a territorial settlement affecting Russia’s borders. Then in the months just before Pearl Harbor the Russians became excessively suspicious of British and American intentions toward their post-war claims. Eden, as a consequence, prepared to leave for Moscow again on December 7. He was informed that the American attitude—and it remained the same to the eve of the Yalta Conference—on the post-war settlement was contained in the Atlantic Charter. We would continue to discuss in general terms problems of a territorial nature, but we would delay any commitments as to specific terms until the end of the war.

At his conference with Eden, following Pearl Harbor, Stalin indicated that he wanted a Soviet-Polish boundary based on the Curzon Line, parts of Finland and Hungary were to be incorporated into the Soviet Union, while the Baltic States were to be absorbed. In addition “Stalin also proposed the restoration of Austria as an independent state; the detachment of the Rhineland from Germany as an independent state or protectorate; possibly the constitution of an independent state of Bavaria; the transfer of East Prussia to Poland; the return of the Sudetenland to Czechoslovakia; Yugoslavia should be restored and receive certain additional territory from Italy; Albania should be reconstituted as an independent state; Turkey should receive the Dodecanese Islands, with possible readjustments of Aegean islands in favor of Greece; Turkey might also receive some territory from Bulgaria and in Northern Syria; Germany should pay reparations in kind, particularly in machine tools, but not in money....

“Stalin said he was willing to support any arrangements Britain might make for securing bases in the Western European countries, France, Belgium, The Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark.

“Eden parried these demands by saying that for many reasons it was impossible for him to enter into a secret agreement, one of which was that he was pledged to the United States Government not to do so. Stalin and he agreed that Eden should take these provisions back to London for discussion with the British Cabinet, and they should be communicated to the United States.”{1}

Our position after this meeting of Stalin and Eden was unchanged: we did not favor territorial settlements until the end of the war. The British, when they signed a treaty of alliance with the Soviet Union on May 26, 1942, also refused to agree to territorial changes at that time. By 1944, however, the progress of the war, particularly in the Balkans, made it clear that some agreement on specific details regarding Europe’s post-war problems had to be made.

On May 30, 1944, British Ambassador Halifax had asked Secretary Hull how the United States would feel about an arrangement between the British and the Russians whereby Russia would have principal military responsibility in Romania and Britain principal military responsibility in Greece. The advance of the Russian armies into the Balkans in April 1944 had brought the relationship between the Soviet Union and the Balkans to the forefront, and Halifax said that difficulties had developed between Russia and the British over the Balkans, particularly with regard to Romania. He explained that the proposed arrangement would apply only to war conditions and would not affect the rights and responsibilities which each of the three Great Powers would exercise at the peace settlement.

Hull expressed opposition to this proposal. The following day Churchill sent a cable to the President urging approval of the proposed arrangement and emphasizing that it applied only to war conditions. Churchill added that he had proposed the arrangement to the Russians and they were willing to accept it but wanted to know whether the United States was in agreement. While the State Department was preparing a reply, Halifax on June 8 brought Hull another message from the Prime Minister. Churchill argued that no question of spheres of influence was involved. He added that it seemed reasonable to him that the Russians should deal with the Romanians and Bulgarians and that the British should deal with the Greeks and the Yugoslavs, who were in Britain’s theater of operations and were Britain’s old allies.

The President sent our reply on June 10, pointing out that the government responsible for military actions in any country would make decisions which the military situation required. On the other hand, the proposed arrangement, he said, might allow these military decisions to extend into political and economic matters. Such a situation, he pointed out, would surely lead to a division of the Balkans into spheres of influence. The United States preferred, he added, to see some consultative machinery to deal with the Balkans.

The Prime Minister cabled back the next day that such machinery would delay action, and he cou...

Indice dei contenuti

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- FOREWORD

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- PART ONE-TRYING TO BUILD A BETTER WORLD

- PART TWO-AT THE CONFERENCE

- PART THREE-THE BALANCE SHEET

- APPENDIX

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Stili delle citazioni per Roosevelt and the Russians

APA 6 Citation

Stettinius, E. (2017). Roosevelt and the Russians ([edition unavailable]). Eschenburg Press. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3025000/roosevelt-and-the-russians-the-yalta-conference-pdf (Original work published 2017)

Chicago Citation

Stettinius, Edward. (2017) 2017. Roosevelt and the Russians. [Edition unavailable]. Eschenburg Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/3025000/roosevelt-and-the-russians-the-yalta-conference-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Stettinius, E. (2017) Roosevelt and the Russians. [edition unavailable]. Eschenburg Press. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3025000/roosevelt-and-the-russians-the-yalta-conference-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Stettinius, Edward. Roosevelt and the Russians. [edition unavailable]. Eschenburg Press, 2017. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.