![]()

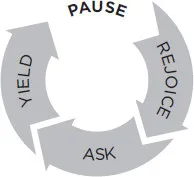

STEP 1: PAUSE

Slowing & Centring

Be still and know that I am God.

(Ps. 46:10)

To start we must stop. To move forward we must pause. This is the first step in a deeper prayer life: put down your wish-list and wait. Sit quietly. Be still. Become fully present in place and time so that your scattered senses can re-centre themselves on God’s eternal presence. Stillness and silence prepare your mind and prime your heart to pray from a place of greater peace, faith and adoration. In fact, it is in itself an important form of prayer.

![]()

3: Slowing & Centring

How to be still before God

All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.

(Blaise Pascal, Pensées)1

The human soul is wild and shy. The Psalmist compares it to a deer panting for streams of water.2 Celtic folklore depicted it as a stag, noble and coy. It hides away from the noise of life, refuses to come on command like some slavering, domesticated pet. But when we are still, it emerges, inquisitive and quiveringly alive.

In prayer, as in life, ‘there is a time to be silent, and a time to speak’ (Eccl. 3:7). If we want to get better at hearing the One who speaks ‘in a still, small voice’, we must befriend silence.3 If we are to host the presence of the One who says, ‘Be still, and know that I am God’, we must ourselves become more present.4 We expect his voice to boom like thunder, but mostly he whispers. We expect him to wear hobnail boots, but he tiptoes and hides in the crowd. We expect him to be strange, but he ‘comes to us disguised as our life’.5

The best way to start praying, therefore, is actually to stop praying. To pause. To be still. To put down your prayer list and surrender your own personal agenda. To stop talking at God long enough to focus on the wonder of who he actually is. To ‘be still before the Lord and wait patiently for him’.6

* * *

When our sons were quite little I would sometimes walk through the door after several days away, only to be greeted by one of them yelling, ‘Dad, have you got anything nice for me?’ or ‘Dad, my brother’s not sharing’, or even, ‘Dad, what’s for dinner?’

‘Well, I’m so glad you’ve missed me!’ I would call upstairs. ‘Any chance of a hug down here?’ I wanted them to acknowledge my presence properly before bombarding me with requests. To look me in the eyes and say very simply, ‘Welcome home, Daddy!’

In a way, this is what Jesus models in the opening lines of the Lord’s Prayer. Before we launch into a long list of all the stuff we need – daily bread, forgiveness of sins, deliverance from evil – he tells us to pause, to address God affectionately as ‘Our Father’, and respectfully, ‘hallowed be your name’.

Prayer can easily become a frenetic extension of the manic way I live too much of my life. Distracted and driven, I step into the courts of the King without modulation, without introduction, without slowing my pace or lifting my face to meet his gaze. But the sages teach us that true prayer is not so much something we say, nor is it something we do; it is something we become. It is not transactional but relational. And it begins, therefore, with an appropriate awareness of the One to whom we come.

The parable of the deranged greyhound and the wild, dog-eating chair

The tranquillity of Guildford’s picturesque cobbled High Street was shattered one sunny morning by the yelping of a dog and a strange metallic clattering.

Suddenly, a crazed greyhound came scrabbling around the corner with its whippet tail between its wild legs, weaving between shouting shoppers, frantic with fear and hotly pursued by one of those cheap chrome bistro chairs. The chair, which was attached to the other end of the dog’s lead, seemed alive, like a dancing snake weaving and flailing, striking and biting at that terrified animal’s rear.

Perhaps the dog’s owner was still inside, unaware of his pet’s plight, innocently queuing for coffee. A movement must have made that chair twitch, which had made the dog jump, which had made the chair leap, which had made the dog scamper, which had made the chair pounce, which had made the dog yelp, which had made shoppers shout, which had made the dog run even more frantically, pursued all the while by this terrifying piece of metal and these crowds of screaming, grabbing strangers. The faster it ran, the wilder the chair’s pursuit, the higher it bounced, the harder it pounced, the louder it banged and clanged and zinged on the cobbles. For all I know, that dog is running still.

We can all live our lives a lot like that demented greyhound. Driven and disorientated by irrational fears, pursued by entire packs of bloodthirsty bistro chairs, too scared to simply stop. And so God speaks firmly into the cacophony of human activity. The Master commands the creature to ‘Sit!’ Jesus rebukes the storm. ‘He makes me lie down’, as the famous Psalm puts it. And, of course, we find it intensely difficult to obey, but as we do so, perspective is restored. Terrors turn back into bistro chairs.

Why is it that so many people today find themselves drawn to the simplicity of marathon running, long-distance cycling, fishing (still Britain’s most popular pastime), the practice of mindfulness, yoga and the cult of ‘de-cluttering’ (ironically now all multimillion-dollar industries)? Why do we binge mindlessly on Netflix at night, and gaze – like monks before icons – at our smartphones on the 07:34 to Waterloo? We seem to be increasingly attracted to activities that put the world’s relentless demands on hold, forcing us to focus for a few eternal moments on a single, simple thing. Hot yoga? Tetris? A lakeside in the pouring rain? Anything to assuage those pesky bistro chairs.

God understands our deep need for stillness, order and freedom from ultimate responsibility, because he has designed us to live humbly, seasonally and at peace. He himself rested and established the Sabbath, inviting each one of us to press pause regularly, saying, ‘Be still, and know that I am God.’7 The Latin for being still here is ‘vacate’ – the very word we use to describe vacating a place or taking a vacation. In other words, God is inviting us ‘to take a holiday, to be leisurely or free’, because this is the context in which his presence is known. Perhaps we might paraphrase this verse: ‘Why don’t you take a vacation from being god, and let me be God instead for a change?’

YOU MUST SEEK SOLITUDE AND SILENCE AS IF YOUR LIFE DEPENDS ON IT, BECAUSE IN A WAY IT DOES

Eugene Peterson says that ‘Life’s basic decision is rarely, if ever, whether to believe in God or not, but whether to worship or compete with him.’8 One of the main differences between you and God is that God doesn’t think he’s you! Moments of stillness at the start of a prayer time are moments of surrender in which we stop competing with God, relinquish our messiah complexes and resign from trying to save the planet. We stop expecting everyone and everything else to orbit our preferences; we re-centre our priorities on the Lord and acknowledge, with a sigh of relief, that he is in control and we are not. Much to our surprise, the world keeps turning quite well without our help. Slowly, our scattered thoughts start to become more centred. Bistro chairs finally settle down.

Selah

The word selah appears seventy-one times in the Psalms – the Hebrew prayer book. It may have been a technical note to the people reciting the Psalm, or to the musicians playing it, but no one really knows for sure what it originally meant or why it is there. Our best guess is that it was an instruction to ‘pause’ and an invitation to ‘weigh’ the meaning of the words we are praying.

Whenever possible, I try to selah at the start of a prayer time by sitting (or sometimes walking) silently for a few minutes without saying or doing anything at all. It’s preferable to do this in a serene environment, of course, but equally possible to find stillness on a crowded train, at a desk in a noisy office, or even hidden in that modern-day hermitage: a toilet cubicle. Stopping to be still before we launch into prayer helps us to re-centre our scattered thoughts, priming our hearts and minds to worship.

If you have a smart phone, it’s a good idea at this point to switch it to flight-mode, not just to prevent interruptions, but also to train your brain to switch off from the abstractions and distractions of life, to become more fully present whenever and wherever you turn to God in prayer.

Pausing before you pray may sound simple – barely worthy of its own chapter – but it is rarely easy. Invariably my mind rebels against any kind of stillness. The greyhound keeps running. The temptation to rush headlong into my prayer list is almost irresistible. A tyranny of demands and distractions strikes up in the unfamiliar silence like a brass band parading around my skull. One Augustinian monk describes it memorably as that ‘inner chaos going on in our heads, like some wild cocktail party of which we find ourselves the embarrassed host’.9

I cannot emphasise too strongly how important it is for your spiritual, mental and physical wellbeing that you learn to silence the world’s relentless chatter for a few minutes each day, to become still in the depths of your soul. You must seek solitude and silence as if your life depends on it, because in a way it does. When you are stressed, your adrenal glands release the hormone cortisol, which impairs your capacity for clear thinking and healthy decision-making. But as you sit quietly, the cortisol subsides and things become clearer. The swirling sediment of life settles down quite quickly. You become more aware of your own presence in place and time, and of God’s gentle, subsuming presence around and within you too.

Stilling the house

Five hundred years ago, St John of the Cross captured the tranquillity of such moments in a lovely phrase: ‘my house now being all stilled’. The lights are off, doors locked, the street outside has fallen silent and inside every living thing has been put to bed. Finally, I am ready to host the whispering King.

Sometimes, having stilled my house, I spend my entire prayer time in silence, simply enjoying God’s presence without saying or doing anything. I used to worry that this wasn’t real prayer – that I had somehow wasted my time – but I have come to understand that these can be some of the most beautiful times of communion. ‘I have calmed and quietened myself, I am like a weaned child with its mother’, as the Psalmist says. ‘Like a weaned child, I am content.’10 In such moments, language becomes unnecessary and even inappropriate. Time stops and words retire. It is enough just to be together like close friends sitting in comfortable silence, without needing to fill the space with a fusillade of speech. In the words of Anthony of the Desert more than sixteen centuries ago: ‘Perfect prayer is not to know that you are praying.’11

Centring prayer

There are several simple practices that can help you to centre your scattered senses as you prepare to pray. It may be helpful to think of them in four steps:

Relax. Start off by sitting comfortably without doing anything for a few moments, perhaps with your palms open in your lap. Take note of the places in your body where you are holding tension, and deliberately relax in each one. Your posture matters. T...