![]()

Chapter 1

Teaching Thinking

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Henry Molaison, or "HM," became a celebrity in the field of neuroscience—not for what he knew, but for what he did not know. In 1953, a surgeon removed a part of Henry's brain, the hippocampi, in an effort to reduce the occurrence of debilitating seizures. When Henry, then 27 years old, awoke from surgery, he could eat, breathe, walk, and talk; he seemed recovered and no longer suffered seizures. Soon, however, it became obvious that Henry had only a few long-term memories, and he was able to remember new experiences for just a couple of minutes, at the most.

Until his death in 2008, HM lived in "permanent present tense," as Suzanne Corkin put it in her 2013 book of that name. HM's procedural memory (what he could "do") was intact, but he had lost the ability to encode, store, and retrieve declarative information (what he needed to "know"). Over the next few years, neuropsychologist Dr. Brenda Milner, would point to his case as proof that people process procedural and declarative knowledge differently. It turns out that the surgeon removed the part of the brain that processes declarative knowledge, so Henry lost the need to think.

Thinking Naturally and Thinking

Humans with intact and healthy brains think. We need to think. We must sort through the thousands of bits of information we take in from the world around us, anticipate multiple reactions that might occur in response to any number of events, plan and predict consequences, and evaluate our actions to make adjustments. In other words, our daily interactions require us to think.

Many of our biological processes are automatic and happen naturally, but many of our procedural capabilities are developed through effort and practice. For example, in life and in school, we can get better at speaking a language, playing an instrument, singing a song, or building a cabinet. Can we get better at thinking?

In The Brain That Changes Itself (2007), psychiatrist Norman Doidge says yes. He describes Michael Merzenich's research that focuses on helping people think better. For example, Doidge writes, Merzenich and his team have developed practical exercises to support what they call the executive functions of the frontal lobes, including, "focusing on goals, extracting themes from what we perceive, and making decisions. The exercises are also designed to help people categorize things, follow complex instructions, and strengthen associative memory, which helps put people, places, and things into context" (2007, p. 90). In summary, Doidge notes that Merzenich's research shows that we can teach people to think better, and Merzenich and others offer training and exercises to support the executive functions. The next question is, are these newly acquired understandings of how the brain works something we can apply in schools?

We say yes. With so much information, imagery, and interaction to process from the outside environment, thinking—inquiry—is something of a survival mechanism. If students can become better thinkers through practice, and research says they can, making this a goal for schooling is both logical and correct. In schools, teachers are familiar with "guided" and "independent" practice time for students, recognizing that it's a necessary component of instruction aimed at building proficiency with procedural curriculum goals. Teachers can teach students to use and practice thinking skills to make meaning of the declarative knowledge in the curriculum and use that knowledge to generate original ideas and products.

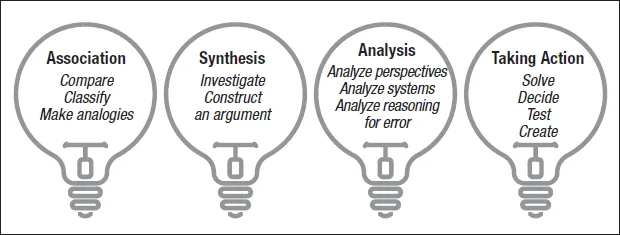

Inquiry skills are a keystone of the i5 approach, which identifies 12 processes that teachers can teach students to use to gain deeper understanding of declarative content knowledge and become better thinkers overall. We group these processes into four categories (see Figure 1.1):

- Association

- Compare: Describe how items are the same and different.

- Classify: Group items together based on shared traits.

- Make analogies: Identify a relationship or pattern between a known and an unknown situation.

- Synthesis

- Investigate: Explain the theme of a topic, including anything that is ambiguous or contradictory.

- Construct an argument: Make a claim supported by evidence and examples.

- Analysis

- Analyze perspectives: Consider multiple takes on an issue.

- Analyze systems: Know how the parts of a system impact the whole.

- Analyze reasoning for error: Recognize errors in thinking.

- Taking Action

- Solve: Navigate obstacles to find a good solution to a problem.

- Decide: Select from among seemingly equal choices.

- Test: Observe, hypothesize, experiment, and conclude.

- Create: Design products or processes to meet standards and serve specific ends.

Figure 1.1. The Skills of Inquiry—aka Thinking Skills

Taken together, these skills can be described as the skills of inquiry, and they've become familiar parts of the curriculum over the past few decades. Chances are, the lessons taught in most classrooms already feature most or all the skills listed above, and students are expected to use each of these processes to varying degrees.

But the critical question is whether teachers are deliberately teaching the skills of inquiry in the same way we might teach the steps of adding fractions, conjugating verbs, creating a website, making an omelet, or serving a volleyball? Do we teach students to compare, for example, or do we assign a task assuming they know how to compare? Do we expect students to be able to analyze points of view, or do we teach them to do this, step-by-step, and then give them the practice they need to get better doing it?

Following the i5 approach means ensuring that the lessons you deliver provide an opportunity for all students to learn to use inquiry skills to process all the declarative knowledge that we teach in school. And it means teaching, scaffolding, and reviewing these skills to help students become better, more innovative thinkers.

Two Types of Knowledge

This is a good place to clarify the confusion about declarative and procedural knowledge. These two types of knowledge are well-illuminated by David Bainbridge, the author of a book that looks at both the anatomy of the brain and the history of neuroscience, Beyond the Zonules of Zinn: A Fantastic Journey Through Your Brain (2008). Bainbridge explains that our brains process procedural and declarative knowledge differently. He describes how our ancestors spent a good amount of time seeking food as they moved through the rich natural environment, where they honed their abilities to see, hear, smell, taste, and touch. We have inherited brains that can move our bodies in productive ways. Exactly as our dogs and cats at home do, we use our cerebellum, or the "little brain," to move (and breathe, digest, circulate blood, etc.). These functions are automatic; procedural knowledge is the name we use for knowledge we have practiced enough times so that, once learned, its application seems automatic. With a bit of DNA and practice, some skills become automatic so that we can do them—reproduce these actions—without thinking.

Bainbridge continues his discussion about the need to procure food and inserts the idea that humans evolved beyond moving toward food (or away from it, in the case that they might become food to other animals) to remembering where food was stored, which food was in which area, and where it might be available again. Our ancestors generated a vast library of labels for this previously experienced information so that they could use it later and in new situations. This led to a much deeper demand than could be handled by just the "little brain." Our "bigger" brains grew to include a prefrontal cortex—an area of the brain that processes the type of knowledge known as declarative knowledge, or anything we know that we might "declare." Although the mechanism has not been pinpointed, we know that the evolution of language in humans coincides with the emergence of our prefrontal cortex. The human brains developed the ability to move our bodies but also to move ideas. The process for moving ideas needed a name to distinguish it from procedural knowledge, and it got one: thinking.

To become more proficient at skills—or procedural knowledge—a person practices. To productively use declarative knowledge, a person thinks. Thinking skills are the brain's way of processing declarative information for retention so that it can be manipulated and reorganized with other information to generate new ways to act.

The process of thinking is slow, and the thinker requires information and time to remember, reorganize, and produce results. In school, some tasks intend for students to reproduce knowledge (procedural goals), and other tasks intend for students to produce a new version of the knowledge (declarative goals).

Now let's identify insights about teaching thinking skills. A teacher can identify whether he or she wants students to learn a topic as procedural knowledge (to reproduce it) or as declarative knowledge (to retain and reorganize to produce an original insight). If the teacher decides to teach a topic procedurally, the students will need lots of practice and feedback. But if the teacher decides to teach information declaratively, then the students will need lots of information and an opportunity to learn and use the steps to one of the thinking skills.

Remember Bainbridge's description of hunters and gatherers moving through the rich environment and gathering input? Compared to the wilderness or a savannah, most classrooms come up short in terms of environmental stimuli; students generally hear and see, but there aren't that many opportunities to use the other senses of touching, tasting, and smelling the learning topic. That means that students need to compensate for the lack of stimulation to gather enough information, imagery, and interaction to set the thinking or inquiry processes in motion. The solution is to use digital devices.

Using technology compensates for the lack of stimulation in a print-only classroom. Complex sensory input is now more readily accessible than ever before, and students can view video and images, hear audio, and actively engage with what seems to be unlimited content and information. In short, the i5 approach informs the "why" of using technology in the classroom and directs digital devices into being a critical element of classroom instruction. It's a means to enrich the way students receive content and create the environment for developing better thinking.

As a side note, technology can be used in a way that improves students' procedural knowledge, too. Access to video, for example, allows students to watch a skill demonstration—and review it multiple times, studying each step as closely and as often as necessary. Access to video recording equipment in the classroom allows teachers and students to document skill development, to track progress, acquire feedback, and practice and perfect repetitive procedures. The caveat is that using technology can bolster procedural knowledge, but it cannot replace carrying out the procedure. You can read about swimming online, but most people agree that until you get in the water and start swimming, you will not become a better swimmer.

Technology deployed to develop declarative knowledge has fewer limitations. It gives students access to a seemingly unlimited amount of information to "think about" compared to what would be available in a non-digital classroom. Because our main concern in this book is the possibilities for teaching thinking that technology has opened we will be focusing on declarative knowledge and the thinking skills, leaving the discussion of using technology to improve procedural knowledge to another author.

How to "i5" Your Lessons

In the simplest application of the i5 approach, revising a current lesson is a matter of answering the "i5 questions":

- How would more information help students see the details and breadth of this lesson's topic?

- How would visual images or nonlinguistic representations add meaning to the topic or give it context?

- How would interacting with others, live or through social media, provide clarifying, correcting, and useful feedback?

- How would teaching or incorporating inquiry—a thinking skill—boost active engagement and questioning with the topic to increase aptitude?

- What innovative ideas or insights could students produce in conjunction with this learning?

Let's take a closer look at each of these key questions and determine why they are so important before we move into lesson planning for teaching thinking and fostering innovation in Chapter 2.

The Role of Information

How would more information help students see both the details and breadth of a topic?

Just 20 years ago, a standard U.S. history textbook provided only one example of a constitution: the U.S. Constitution. Today, students can research information about "constitutions" online and find documents from dozens of countries in their native languages and translated into English. This breadth of content adds to students' understanding of nations and lays the groundwork for in-depth analysis using a higher-order thinking skill such as comparing different documents to find similarities and differences among them.

In Think Better: An Innovator's Guide to Productive Thinking (2008), Tom Hurson writes, "More than any other commodity, information is everywhere. Not only can almost anyone access almost anything at almost no cost, but, unlike corn and wheat, information doesn't have to be consumed to be used. Quite the opposite: the more it's used, the more it grows" (pp. 9–10).

In a classroom today, when Donna Martin teaches a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks or a novel by Gabriel García Márquez, her students have access to biographies, images of where and how these writers lived, critiques by both those who support and those who question their work, and, of course, recommended works shared by hundreds of people around the world. Ms. Martin says that when she is planning to deliver the new information in her lessons, digital sources are critical. She can direct students to visit websites to find biographical or autobiographical information; she teaches students to search for the right information they need to answer questions but also to delve deeper.

In Belinda Parini's physical education classes, students learn about factors that affect fatigue. Ms. Parini says she now plans instruction time to include short segments for students to search for information online. By reading athletes' own writings, accessing data charts, and studying current science articles that support the knowledge of metabolic changes, students improve their abilities to predict fatigue fac...