eBook - ePub

Digital Skills

Unlocking the Information Society

Kenneth A. Loparo, Kenneth A. Loparo

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Digital Skills

Unlocking the Information Society

Kenneth A. Loparo, Kenneth A. Loparo

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The first book to systematically discuss the skills and literacies needed to use digital media, particularly the Internet, van Dijk and van Deursen's clear and accessible work distinguishes digital skills, analyzes their roles and prevalence, and offers solutions from individual, educational, sociological, and policy perspectives.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Digital Skills è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Digital Skills di Kenneth A. Loparo, Kenneth A. Loparo in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Éducation e Éducation générale. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

ÉducationCategoria

Éducation généraleCHAPTER 1

Introduction

The Deepening Divide

In the first decade of the twenty-first century, the attention given to the so-called digital divide in developed countries gradually decreased. The common opinion among policy makers and the public at large was that the divide between those with access to computers, the Internet, and other digital media and those without access was closing. In some countries, 90 percent of households were connected to the Internet. Computers, mobile telephony, digital televisions, and many other digital media decreased in price daily while their capacity multiplied. On a massive scale, these media were introduced in all aspects of everyday life. Several applications appeared to be so easy to use that practically every individual with the ability to read and write could use them.

Yet, we posit that the digital divide is deepening. The divide of so-called physical access might be closing in certain respects; however, other digital divides have begun to grow. The digital divide as a whole is deepening because the divides of digital skills and unequal daily use of the digital media are increasing (Van Dijk, 2005). One can even claim that as higher stages of universal access to the digital media are reached, differences in skills and usage increase. In this book, we will argue that digital skills are the key to the entire process of the appropriation of these new technologies. These skills are vital for living, working, studying, and entertaining oneself in an information society.

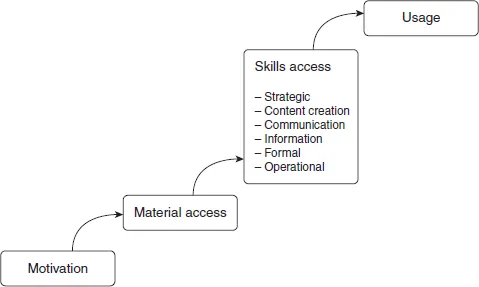

We consider access to be the complete process of appropriation of a new technology. Having or possessing the required equipment and reaching a connection—obtaining so-called physical access—comprise only one step in this process. This step is a necessary one; however, it is not decisive in the process that leads to the ultimate goal of satisfactorily utilizing the technology for a particular purpose. This can be explained using the model in figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Four Stages of Access to Digital Technology.

Source: Van Dijk, 2005, p. 22 (adapted).

Motivation is the first stage in the process of appropriation of a new technology. People who do not like computers or other digital media will not attempt to purchase one or obtain a particular connection, unless they are forced to do so. In the 1980s and 1990s, phenomena such as computer anxiety and technophobia were quite common. Fear of the new technologies touched a large part of the population, and negative or critical views of the effects of the new media on man and society were popular. In the second half of the 1990s, with the breakthrough of the World Wide Web and the increasing popularity of the Internet, these fears and views began to change. Around the year 2000, the Internet even turned into hype. In the decade that followed, the Internet merged completely into the everyday life of developed countries. At present, the elderly and people who are barely able to read and write are also motivated to obtain access to and use digital media, regardless of the perceived difficulty of these media. Instinctively, these people realize that they will become marginalized in society if they do not use digital media. However, computer anxiety still exists, and the levels of motivation differ substantially across sections of the population.

Motivation is not only crucial for the decision to purchase a computer and obtain a connection to the Internet but even more important for the steps needed to use these media and become familiar with them. Developing the necessary skills requires continuous effort and motivation. When all goes well, when the command and usage of digital media are simple, and occur according to the needs and goals of people, the result is stimulation. Then, a cycle of increasing motivation begins.

The second stage of appropriation, acquiring physical access to digital media, has completely dominated public opinion and policy perspectives in the last two decades. This dominance is evident in that many people believe that the access problem is solved and that the digital divide is closed when more than 90 percent of the population have a computer and Internet access. Then, the Internet can be put on par with television. Importantly, the diffusion of the Internet in the last two decades was even faster than that of television. While it took 17 years for television to reach a 30 percent household diffusion level in the United States, the Internet achieved the same rate in only 7 years (Katz & Rice, 2002). However, reaching the remaining population might be more difficult for the Internet than it was for television. In Northern and Western Europe and in South Korea, Internet access rates are reaching 90 percent figures; however, in Southern and Eastern Europe, they remain between 30 and 60 percent (Eurostat Statistics 2013). In the United States, household Internet access in 2012 was 81 percent, with large differences between urban and rural regions. However, on a world-scale, Internet access in 2012 was only 35 percent, with several developing countries below 10 percent (International Telecommunications Union, 2013).

Moreover, physical access is not equal to material access. Material access includes all costs of the use of computers, connections, peripheral equipment, software, and services. These costs are diverging in many ways, and people with physical access have quite different computer, Internet, and other digital media expenses. Differences in the types of connections and hardware employed, for example, have remained stable (e.g., Davison & Cotten, 2009; Pearce & Rice, 2013). Although the physical access divide will close in the long run, material access divides will remain and perhaps become even more prominent. The innovation of information and communication technologies (ICTs) is not slowing, and continually more or less expensive new hardware and software are invented. Service innovation also leads to greater or fewer expenses for those with different needs and incomes.

Access and Beyond

The third stage of the appropriation of digital media consists of the skills necessary to master them. The main message of this book is that these skills are the key to the entire process. We prefer to use the term “skills” over “literacy” or “competence,” which are concepts that are also frequently used in the literature (separately or in combinations such as “literacy skills” or “literacy competence”). Literacy can be considered the most general concept and is often considered as a set of skills or competencies. The term “literacy” has had a variety of meanings over time. The simplest form of literacy involves the ability to use language in its written form: “A literate person is able to read, write, and understand his or her native language and express a simple thought in writing” (Bawden, 2001, p. 220). A more general definition considers literacy as the skills that are needed to perform well within society. When the context is also considered, being literate becomes “having mastery over the process by means of which culturally significant information is coded” (De Castell & Luke, 1988, p. 159).

Anttiroiko, Lintilä, and Savolainen (2001) concluded that there are two dimensions of competence: knowledge and skills. They defined knowledge as the understanding of how our everyday world is constituted and works, whereas skills involve the ability to pragmatically apply, consciously or unconsciously, our knowledge in practical settings.

In our view, the term “skills” suggests a more (inter)active performance in media use than, for example, the term “literacy,” which refers to reading and writing texts. For instance, using the Internet extends beyond reading and writing on keyboards and screens to include interacting with programs and other people, or completing transactions for goods and services. Internet use requires more action than the relatively passive use of visual media such as television or books, which mainly require knowledge and cognitive skills. Thus, in addition to tool-related skills, specific skills are also needed to use the provided information or communicate over the Internet. The following chapters will extensively discuss different types of digital skills. We propose the following skills: operational, formal, information, communication, content creation, and strategic skills. These skills are overviewed at the end of this section and fully explained in the following chapter. They are the central part of this book.

The fourth and final stage of appropriation of digital media reaches its ultimate destination, usage. Usage is determined by two large factors: motivation (interest in particular applications and in the use of computers and the Internet in general) and skills (Van Dijk, 2005). Usage patterns consist of the frequency and length of time per day that the digital medium is used, the number and variety of applications, the types of applications used (for example, information, communication, commerce, work, entertainment, and education), and the type of use (productive and user-generated or consumptive). All of these variations are correlated with the demographics that are frequently examined in digital-divide research, that is, age, gender, educational level, occupation, household composition, and ethnicity (e.g., Hargittai & Hinnant, 2008; Livingstone & Helsper 2007; Van Deursen & Van Dijk, 2014a).

In this book, we will show that usage is also correlated with one or more of the skills mentioned in the former paragraph, although not in the simple and straightforward way that many suppose. It is common opinion that skills are developed with increasing frequency and time of use or what is called experience. We will show that this applies partly to the operational and formal skills, but not to the “higher” content-related skills of information, communication, content creation, and strategy. These are social and intellectual skills that must be developed before one begins to use computers, the Internet, and other digital media. While using digital media, these skills must be transformed and adapted to the special information, communication, and strategic requirements of the medium concerned. For example, searching for information in a library is quite different from searching for the same information in a search engine on the Internet.

With the large-scale diffusion of digital media in society and everyday life, many variations in the use of these media tend to grow as they mix with social, economic, and cultural differentiations in society. As these differentiations have also grown in contemporary (post)modern society, social and usage differences are likely to reinforce each other. The same is true for skills and for social, economic, and cultural differences. In this book, we will show that the skill levels attained differ among social and demographic categories. In addition, these skill differences create greater or fewer opportunities in social positions, for example, in the employment market and social networking.

With further diffusion of the digital media into society, the focus of the digital divide extends beyond physical or material access and shifts to the stages of skills and usage. In the digital-divide literature after the year 2000, this is expressed with different, but similar, concepts. Kling (2000) suggested a distinction between technical access (material availability) and social access (the professional knowledge and technical skills necessary to benefit from information technologies). Attewell (2001) has distinguished between first and second digital divides. Hargittai (2002) suggested the most familiar expression of a first- and second-level digital divide. DiMaggio and Hargittai (2001) suggested the following five dimensions along which divides may exist: technical means (software, hardware, and connectivity quality), the autonomy of use (location of access and freedom to use the medium for one’s preferred activities), use patterns (types of uses of the Internet), social support networks (availability of assistance with use and the size of networks to encourage use), and skill (one’s ability to use the medium effectively). Warschauer (2003) argued that besides physical access, factors such as content, language, literacy, educational level attained, and institutional structure must be considered. Van Dijk (2005) has made the four-stage distinction that is shown in figure 1.1.

Among all of these concepts and types of access to the digital media and beyond, this book will concentrate on skills. In our opinion, skills are increasingly the key variable of the entire process of access and information inequality in the information society.

A Range of Skills

In this book, we propose the following range of skills:

1.Operational skills. The popular and policy attention to digital skills is completely focused on “operational skills.” These are the technical competencies required to command a computer or the Internet. In popular language, they are called “button knowledge.”

2.Formal skills. In the improved interpretations of these technical competencies, attention is paid to browsing and navigating the Internet. This is what we call “formal skills.” Every medium requires such skills because each has a number of formal characteristics. A book has chapters, paragraphs, a table of contents, and sometimes an index and references. Television has channels and programs. The Internet has sites with menus and (hyper)links. Users must learn these characteristics with every medium. Computers and the Internet are no exception. It is known that many elderly and illiterate people have problems thinking and acting in terms of menu structures and using hyperlinks.

3.Information skills. Less attention has been paid to so-called information skills, the ability to search, select, and evaluate information in digital media. These are especially needed in media that offer an overload of sources and content to choose from, such as the Internet. While operational and formal skills are medium-related skills, information skills are content-related.

4.Communication skills. “Communication skills” are needed for digital media such as the Internet that increasingly concentrate on communication. The use of email, chatting, instant messaging or tweeting, preparing profiles on social media or online dating, and contributing to online communities require special communication skills; however, there is no school to learn them.

5.Content creation skills. In the last ten years, “content creation skills” have become increasingly important, as the Internet has developed from a relatively passive content consumption medium to a medium that enables actively produced user-generated content. This development is known as Web 2.0. Content creation is no longer only the design and publication of a personal or professional website, as in the 1990s; it also refers to the writing of text (as in blogs, Tweets, or on online forums), the recording or assembling of pictures, videos, and audio programs (as in photo, video, or music exchange sites), or compiling a personal profile and producing messages and images on a social networking site. These activities previously required professional skills. However, accessible software on the web now seems to offer nearly every individual the opportunity to develop amateur skills for these activities. The software is often deceivingly simple, leading the users to believe that they can make eff...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover

- Title

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Defining Internet Skills

- Chapter 3 Impact: Why Digital Skills Are the Key to the Information Society

- Chapter 4 Current Levels of Internet Skills

- Chapter 5 Solutions: Better Design

- Chapter 6 Solutions: Learning Digital Skills

- Chapter 7 Conclusions and Policy Perspectives

- References

- Index

Stili delle citazioni per Digital Skills

APA 6 Citation

Deursen, A. van, & Dijk, J. van. (2014). Digital Skills ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan US. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3487123/digital-skills-unlocking-the-information-society-pdf (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

Deursen, Alexander van, and Jan van Dijk. (2014) 2014. Digital Skills. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://www.perlego.com/book/3487123/digital-skills-unlocking-the-information-society-pdf.

Harvard Citation

Deursen, A. van and Dijk, J. van (2014) Digital Skills. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3487123/digital-skills-unlocking-the-information-society-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

Deursen, Alexander van, and Jan van Dijk. Digital Skills. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan US, 2014. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.