eBook - ePub

The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America

Historical and Comparative Perspectives

Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki, Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America

Historical and Comparative Perspectives

Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki, Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The public provision of early childhood education has developed at different rates across individual countries over the past two centuries. This book provides the historical background to explain how these national differences occurred, with particular reference to welfare and educational systems, to highlight how particular influences grew.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America di Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki, Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe, Kristen Nawrotzki in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Éducation e Administration de l'éducation. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

ÉducationCategoria

Administration de l'éducation1

Introduction: The Longue Durée – Early Childhood Institutions and Ideas in Flux

Harry Willekens, Kirsten Scheiwe and Kristen Nawrotzki

Across Europe and North America (and in other parts of the world to which we can claim no expertise), we have witnessed in recent decades a spectacular development of institutions and arrangements designed for the education and care of young children (those under compulsory school age) outside the family. In no society have young children ever been raised by their parents alone, but, with a few exceptions, collective education and care in the past took place within networks of individuals who knew each other and who were tied to each other by complex social obligations (e.g. networks of kin or neighbourhood solidarity). The early childhood education and care (henceforth ECEC) which has come to define the life of young children in contemporary societies is of a wholly different nature: it is always regulated and often directly supplied by the State; its establishment has most often been the result of intentional policies pursuing specified social goals; and the individuals providing the services do so for money and not on the basis of personal ties with the parents or children.

There is no doubt that developments everywhere have gone in the same direction of having more and more young children in ECEC for ever longer hours. A universal motor of these developments has been the integration of women into the labour force starting in the 1970s, which raised the question of how to take care of young children while their mothers were at work. The issue was all the more pressing because the networks of neighbourhood and kin solidarity, which had been performing childcare for millennia, were loosening at the same time that mothers were being (re)drawn into the workforce: with increasing social and geographical mobility, the distance to friends and kin tended to become too great to systematically involve them in childcare; furthermore, said networks had been constituted mainly by women – whose own participation in paid work made them less available to help others.

But if the question of the reconciliation of childcare and gainful employment was dominant in most of Europe and North America from the 1970s until the end of the twentieth century, educational goals – some altogether new – have come to overlay the reconciliation motive over the last decade and a half. In the main, there are two considerations at work here. First, early childhood education (henceforth ECE) is, on the one hand, assumed to be necessary for the social integration of the children of immigrants (see Honig, Schmitz and Wiltzius on Luxemburg, Chapter 13) or for the proper upbringing of the children of the ‘unfit poor’ (see Michel on the United States, Chapter 14). On the other hand, there is also a tendency for ECE to be conceived as a beneficial first step in the development of all children’s ‘human capital’, of their ability to function and flourish in the economy of the future (see UNICEF 2008, which even ranks countries with regard to their progress towards this goal; Mahon 2013; Michel, Chapter 14).

This story is well known, having been described in a substantial body of national and comparative literature on the development of ECEC since the 1970s.1 For all of its strengths, however, the literature suffers from a crucial limitation which this volume seeks to redress. Either much of the existing research focuses on the present and the future without going into past developments at all, or else it goes back only to the point in time at which employment-related public childcare began its swift expansion at about 1970. This narrow focus on the recent past makes it difficult to understand developments (and especially the differences between developments in different countries) which have their roots in the more distant past. Some countries, such as Sweden, Norway and Iceland, were in a position to start building a new planned system of ECEC in the 1960s and 1970s, for the simple reason that ECEC had been a marginal social phenomenon until then. In most European Catholic countries, by contrast, ECE (though much less so care per se) could look back on a long history by the 1970s, as several chapters in this volume attest. Consequently, all attempts at ECE reform in those countries had to deal with vested interests and crystallized ways of doing things. The differences between these different chronologies and trajectories of ECE and ECEC, not to mention the difficulties of introducing new forms of ECEC in the face of existing traditions and institutions, cannot be understood if one disregards everything which happened before the era of reforms in the 1960s and 1970s took off. The chapters in this volume go back as far in time as we think necessary to enable us to explain the differences and similarities in the organization of ECEC – but especially ECE – in several countries.

Research questions and their connections to our earlier research

This book was preceded by an earlier volume on childcare and preschool development in Europe (Scheiwe and Willekens 2009a), which contains a number of case studies of developments in European countries as well as some comparative essays. That overview of (Western) European developments enabled us to identify two basic ideal types of ECEC: an ‘educational model’ and a ‘work-care reconciliation model’ (Scheiwe and Willekens 2009b, pp. 4–10). This distinction is related to the motives for public policies. The educational model presumes that young children need not only care but also some public education and learning below the age of compulsory schooling. The basic motive underlying the second model is the reconciliation of care work and paid work, which has two variants: an older one, based on the premise that if mothers are economically forced to do paid work, something must be undertaken to care for the children; and a newer one, which sees public childcare as a necessary precondition for mothers to participate in the labour market.2 Thus, the old model was defined by the view of mothers’ employment as a problematic and undesirable but sometimes necessary circumstance, and care in that case sought to mitigate the immediate damage that mothers’ employment did to children (leaving them under-supervised, or in otherwise poor conditions). The newer variant, something of a 180-degree turn, sees mothers’ employment not only as desirable but also as a necessary means for improving the economic circumstances for whole families and as a key to national economic well-being.

In terms of clientele, the educational model can focus on the lower classes, but it tends to be universalist: education is a benefit to all, and educational provision will therefore tend to be open to all comers of the right age category. The work-care reconciliation model, obviously, only aims at children without a stay-at-home parent; it used to be a provision for the working class alone, and it is only recently, as a result of the normalization of maternal employment across the socio-economic spectrum, that it has started to tend to universalism. The educational model makes no explicit assumptions about gender relations; moreover – especially before the late twentieth century – those espousing the educational model were sometimes at pains to show that ECE did not encourage mothers to work, for example, by insisting that ECE provision be scheduled on a part-time or irregular basis (Hagemann et al. 2011). This, in turn, emphasized the institutional separation of care from education. For its part, the reconciliation model has come to be associated with the idea of equal opportunities for men and women, marking a significant change from its origins in the nineteenth century.

The different goals and underlying assumptions of the two models affect the various institutional dimensions of ECEC (Scheiwe and Willekens 2009b, p. 9). Educational establishments tend to be open to all, subject to school laws and administered by ministries of education (compensatory education targeted specifically at the poor as we see in the United States and England deviates from this trend; cf. Nawrotzki, Chapter 8). Their time schedules are often coordinated with those of schools (which themselves are sometimes inconvenient for parents requiring childcare), and the staff are trained in education. Within the reconciliation model, parental employment is a condition for the use of the provision; the rules of access prioritize certain groups; their regulation is part of welfare law; the provision is administered by the welfare branch of government; the staff are trained as social or health workers; and the time schedules are adapted to the needs of the parents.

In real life, there is of course a tendency for the two ideal types to blend together. Parents use ECE as childcare, and provision with a strong focus on childcare also educates young children. Furthermore, the institutionalization of ECEC must not of necessity develop in accordance with either an educational or a reconciliation model. In our earlier research, we nevertheless observed that there was very little institutional blending of the two policy motives before the 1970s. We found that in some countries (Belgium, France and, to a lesser extent, the Netherlands, Italy and Spain) public education for the three- to six-year-olds had been institutionalized and was basically aimed at the whole population (even if in most of these countries before 1960 less than half of the population was effectively in ECE); while in a number of other countries (e.g. Germany, Austria, Switzerland and the Nordic countries), an approach prevailed in which there was subsidiary and rather marginal childcare provided for children who were thought to otherwise be unattended or at risk, with less of a fixed institutional form (and therefore much more variety than in the countries of the first type).

Everywhere early institutionalization occurred, educational and custodial childcare establishments were separated from one another and subject to different legislation and administration. It is only during the last few decades that a tendency to merge the two policy motives into one institutional framework was discerned, especially in the countries where no early institutionalization had taken place and where the policymakers therefore had more leeway to develop a new ECEC regime, such as in Denmark (Borchorst 2009; Bertone, Chapter 12), Sweden (Bergqvist and Nyberg 2002; Leira 2006; Korsvold 2012), Norway (Leira, Chapter 6) or Luxembourg (Honig et al. Chapter 13). The latest developments, which, at least at the level of goal-setting, stress the importance of education for the (even very) young as a way of building human capital, also tend to bring the two basic approaches closer together.

Contemporary differences between national regimes can be expected to have historical roots; what surprised us in the previous volume was the finding that events in the distant past may have been just as influential (or even more influential) than those in recent decades. Therefore, the present work focuses much more systematically on long-term developments over the last 200 years. From this, it followed that the present volume should examine ECE, as that was the most common type of public institution for young children over much of the longue durée, all the way up to the 1960s. Childcare is not completely excluded, however, for many chapters in this book also address developments after the mid-twentieth century, when childcare became a widespread policymaking concern alongside ECE. Moreover, in some cases, nearly everything worth reporting occurred only after 1960; in such cases, either the developments in education and in care were inextricable, or else they strongly impacted on each other that they bear joint examination.

Within the strong focus upon education, there are two basic research questions. First, what paths did institutionalized ECE take in different countries of Europe and North America, and how similar or different are they? Second, how may these similarities and differences be explained?

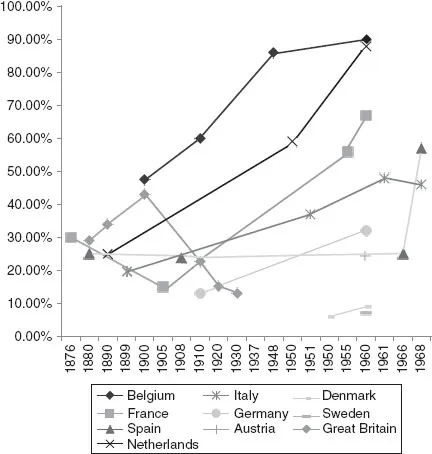

Surprisingly there is very little comparative scholarship regarding the history of ECE or of ECEC. Some very good national histories of ECE exist, but most lack the comparative perspective (and some are inaccessible to readers of only English).3 There are also a few extremely valuable scholarly contributions comparing a few countries in great depth (e.g. Morgan 2003) or else a number of countries from the bird’s eye view of macrosociology, classifying different ECE regimes according to sociological criteria without going into the intricacies of their respective historical developments (Bahle 2009). But that is all. The paucity of the literature is more striking in the face of the remarkable national (and regional) differences in the development of the form, quantity and quality of ECE. This is illustrated in Figure 1.1, which allows for the comparison of the quantitative national differences in the early spread of ECE, first around 1900 and then around 1960, before the second wave of ECE expansion began.

Our previous research suggests that the ‘usual’ explanations for national policy differences in welfare state comparison do not apply for ECE. For the period before 1970, for example, we found no evidence that ECE developed earlier in richer countries or in those with an early development of the welfare state, nor does it appear that the development of ECE had much to do with a rise in female employment. We found evidence, on the other hand, that conflicts over educational hegemony between the Catholic Church and anti-clerical forces may have played a decisive role in the development of ECE in some countries (see Bahle 2009 and Willekens 2009b), suggesting both that the longue-durée approach is a fruitful one and that much is unknown about the forces at play in shaping the institutionalization of ECE. It is one of the aims of this book to further explore the potential causes of differential ECE developments.

Method

In order to answer these research questions, we have decided to broaden the geographical scope of our inquiry by including North America, besides various European countries, to strengthen the comparative basis of our observations, to focus strongly on developments in the longue durée and to include the issue of the diffusion of ideas, practices and institutions across space and time.

Figure 1.1 Children aged three to five in ECE

Sources: Missing years do not imply a lack of ECE provision. The Netherlands data apply to children from age four; Swedish statistics include children under age seven; British statistics include only ages three and four since five-year-olds were compelled to attend school. Given the lack of comparative data for that time, data for several countries have been compiled from Bahle (1995); for Italy: Catarsi (1994, p. 30) and Ferrari (1999, p. 123f.); for Spain: Sanchidrián (2009, p. 455); Austria: Scheipl (1993, p. 6); Germany 1910: Erning (1987, p. 30), Germany 1960: Hagemann (2006, p. 232); France: Grew and Harrigan (1985) and Martin and Le Bihan (2009); Great Britain: Great Britain Board of Education (1912) and Great Britain Board of Education, Consultative Committee (1933).

We have extended the geographical scope of our research by including the United States and Canada, as well as several countries which are under-represented in the existing comparative literature (namely, Norway, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the former German Democratic Republic). We have also, for different reasons, included reports on several countries already represented in our first volume. Whereas the reports on France and Spain in the previous volume had a strong focus on the childcare policies of recent decades, the new chapters examine what went on before. Germany and Britain were also included in the first volume; they are here again, but in the context of specific comparative questions which could not be dealt with in single-country case studies.

Our focus on the description and analysis of long-term developments permits the identification of critical junctures and breakthroughs in the history of ECE. While in some cases (such as in Belgium or France), the late nineteenth-century developments were decisive in determining the later features of ECE(C), in other cases it was only in the 1950s (Netherlands, German Democratic Republic), 1960s (Italy, Denmark), 1970s (Sweden, Spain), 1990s (Germany) or even 2000s (Luxembourg) that ECE(C) received impulses which would prove to be definitive of its later structure. The identification of the conflicts, actions and events, which had an influence on the development of ECE(C), is only possible if one is prepared to reach back in history to a time at which ECE(C) had not yet been institutionalized; otherwise, one is bound to overlook factors which were crucial to its development.

Testing explanatory hypotheses about the development of social institutions is possible only by either comparing cases in which similar developments can be observed (and then looking for the potential causes of such developments the cases might have in common) or contrasting cases in which developments differ (and then searching for potential causes present in one case, but not in the other...

Indice dei contenuti

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Introduction: The Longue Durée – Early Childhood Institutions and Ideas in Flux

- Part I: ECE(C) Developments in the Long Term

- Part II: Actors and Critical Junctures in the Development of ECE(C)

- Index

Stili delle citazioni per The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2015). The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America ([edition unavailable]). Palgrave Macmillan UK. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3490509/the-development-of-early-childhood-education-in-europe-and-north-america-historical-and-comparative-perspectives-pdf (Original work published 2015)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2015) 2015. The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America. [Edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://www.perlego.com/book/3490509/the-development-of-early-childhood-education-in-europe-and-north-america-historical-and-comparative-perspectives-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2015) The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3490509/the-development-of-early-childhood-education-in-europe-and-north-america-historical-and-comparative-perspectives-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Development of Early Childhood Education in Europe and North America. [edition unavailable]. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.