![]()

Chapter One

INTRODUCTION: THE RECIPROCAL PARTICIPATION-POLICY RELATIONSHIP

SOME GROUPS participate more than others—the affluent more than the poor; the educated more than the uneducated; whites more than blacks and Latinos; the elderly more than the young. Does it matter? Do high-participation groups get more of what they want from the government? Do participatory inputs shape policy outputs? Critics allege that the American system of government inadequately represents the interests of the underprivileged, to their detriment.1 Indeed, one motivation driving researchers to measure participatory differences across groups is an assumption that they lead to unequal policy outcomes. Do they?

And why are some groups more politically active than others? We know part of the story—some individuals possess more politically relevant resources, like income and education, than others, some are more interested in public affairs, and some are more likely to be recruited to participate. And these factors arise from early socialization at home and in school and from affiliations with voluntary associations, workplaces, and religious institutions.2 But what about the role of public policy? Might government policy also be a source of political resources, a sense of stake in the system, even a mobilizing factor?

This book focuses on the reciprocal relationship between political participation and public policy. I show that mass participation influences policy outcomes—the politically active are more likely to achieve their policy goals, often at the expense of the politically quiescent. And the ability of the politically active to do so is in part a legacy of existing public policy—policy influences the amount and nature of groups’ political activity, often exacerbating rather than ameliorating existing participatory inequalities. Public policies can confer resources, motivate interest in government affairs by tying well-being to government action, define groups for mobilization, and even shape the content and meaning of democratic citizenship. These effects are positive for some groups, like senior citizens, raising their participation levels. For other groups, government policy can have negative effects. Because of the difficult and demeaning experience of obtaining welfare, for example, its recipients participate at rates even lower than their modest socioeconomic situations would predict.3 These effects feed back into the political system, producing spirals in which groups’ participatory and policy advantages (or disadvantages) accrue. Citizens’ relationships with government, and their experiences at the hand of government policy, help determine their participation levels and, in turn, subsequent policy outcomes.

With its influences on participation, public policy affects the basic mechanisms of democratic government. An important function of government is the allocation of societal goods. In a democracy, the people are supposed to voice their preferences through their political participation. Indeed, democratic theory is predicated on the equal ability of citizens to take part in this way.4 But policy design—who gets benefits, how generous they are, and how they are administered—affects groups’ participatory capacities and interests. The distributional consequences are profound. Policy begets participation begets policy in a cycle that results not in equal protection of interests, but in outcomes biased toward the politically active. Thus the very quality of democratic government is shaped by the kinds of policies it pursues.

Senior citizens in the United States and their activity in relation to Social Security form the empirical basis for this study. Social Security and Medicare transfer 40 percent of the federal budget to seniors, with significant effects on their political behavior. They are the Über-citizens of the American polity, voting and making campaign contributions at rates higher than those of any other age group. They also actively defend their programs, warning lawmakers through their participation not to tamper with Social Security and Medicare. The result is continued program growth, even as programs for the poor are cut.

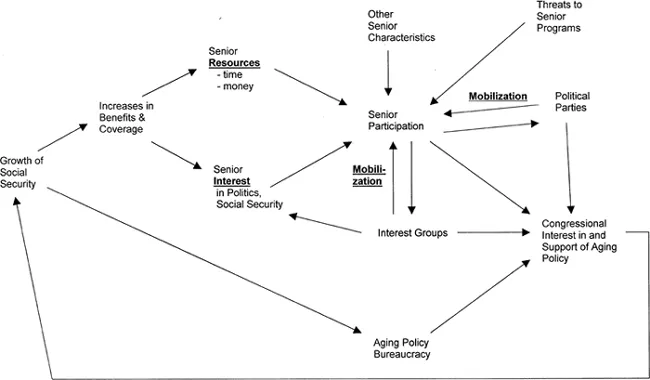

Seniors were not always so politically active. In the 1950s, when Social Security benefits were modest and covered only a fraction of seniors, the elderly participated at lower rates than younger people. The growth of the program in part fueled the increase in senior participation over time. Social Security provided the once-marginalized senior population with politically relevant resources like income and free time. The program increased seniors’ engagement with politics by connecting their fortunes tangibly and immediately to government action. It fashioned for an otherwise disparate group of people a new political identity as program recipients, which provided a basis for mobilization by political parties, interest groups, and policy entrepreneurs. And Social Security incorporated seniors into the highest level of democratic citizenship, their relationship with the state marked by full social and political rights and privileges, including the right to fend off proposals for program change that they find objectionable. Indeed, Social Security (and Medicare) have provided two stimuli: the growth of the programs, which has enhanced seniors’ participatory capacity over time, and threats to the programs, which have inspired participatory surges that lawmakers heed and that protect the programs from retrenchment efforts. The combination of these stimuli produces a loop in which senior welfare state programs expand: the programs enhance seniors’ participatory capacity so that when their programs are threatened they are able to defend them; thus protected, the programs continue to augment seniors’ participatory capacity (figure 1.1). In short, Social Security helped create a constituency to be reckoned with, a group willing, able, and primed to participate at high rates, capable of defeating objectionable policy change.

Welfare recipients are not so fortunate. In contrast to Social Security, welfare has negative effects on its clients. Welfare recipients do have an interest in public affairs arising from their dependence on government action, but this level of interest is lower than that of Social Security recipients and cannot by itself enhance participation levels—adequate political resources and mobilization are needed too, and here welfare recipients are severely disadvantaged. Indeed, the design of welfare, which requires recipients to meet with caseworkers who ask probing personal questions and who appear to have great discretion over benefits, undermines recipients’ feelings of efficacy toward the welfare system and the government in general, reducing their rates of political participation.5 The lack of positive policy feedbacks helps make welfare an easier fiscal target and contributes to greater retrenchment in that policy area.

THE INFLUENCE OF PARTICIPATION ON POLICY

The participation literature has made impressive empirical and theoretical gains in explaining who is politically active, but has largely neglected the crucial question of differential policy outcomes. As the dean of participation scholars, Sidney Verba, notes, there has been much emphasis on equal capacity and equal voice across demographic groups, but understanding the real result of participation requires consideration of equal outcomes. The literature assesses what individuals do rather than what effect their activity has, which is a far more difficult and complex task.6

Anecdotally we can think of high-participation groups prevailing in the policy arena and low-participation groups suffering: during the 1990s the wealthy saw capital gains tax rates reduced while welfare lost its entitlement status. But linking participatory inputs to policy outcomes is difficult, and has rarely been done systematically.

There have been some attempts to connect participation and policy. Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward argue that low turnout rates among the poor result in public policy that favors higher-status voters.7 Kim Quaile Hill and Jan Leighley find a correlation between turnout among the poor and levels of welfare spending among the fifty states.8 But these studies use voter turnout, a “blunt” instrument of participation for which issue content must be assumed.9 That the poor participate less is compatible with the notion that the highly participatory prevail in the policy arena, but does not itself make the link. No single study has yet connected the dots and shown conclusively that differential participation rates across groups influence policy outcomes.

Figure 1.1 The participation-policy cycle

PROGRAM DESIGN AND THE INFLUENCE OF POLICY ON PARTICIPATION

Thanks to advances in polling technology over the past half century, we know a great deal about who participates in terms of education, income, race, ethnicity, and gender. And increasingly sophisticated models tell us why some individuals and groups participate more than others. One factor past work leaves out is the effect of government policy.

In their seminal 1972 work, Participation in America, Sidney Verba and Norman Nie showed that participation of all forms, from voting to protesting, is more common among individuals of higher socioeconomic status (SES), which they measured with an index combining education, income, and occupation. In Who Votes? (1980) Raymond Wolfinger and Steven Rosenstone took the SES model one step further, disaggregating SES into its three components. They found that education has the most profound effect on voting.

In the most recent major work on political participation, Voice and Equality (1995), Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry Brady develop a Civic Voluntarism Model to explain the mechanisms by which SES influences participation. Political activity is fueled by three “participatory factors”: resources, like income and politically relevant skills; engagement with politics, including political interest and knowledge; and mobilization. These factors arise from personal characteristics, preadult experiences at home and school, and affiliations with the workplace, religious institutions, and voluntary organizations.

Although these developments in the participation literature have considerably enhanced our understanding of participatory differences, they have largely ignored policy influences on would-be participators—how government policies might influence these participatory factors. The policy feedbacks literature in American and comparative politics suggests that policy effects are central. The work of historical institutionalist scholars such as Theda Skocpol, Paul Pierson, Sven Steinmo, and Peter Hall shows, at the macro level, how existing policy structures constrain subsequent policymaking. Current policies foreclose some possibilities, preordain others.10 For example, Skocpol argues that the extensive system of pensions for Civil War veterans delayed the broader implementation of old-age pensions for decades, because of their association with corrupt patronage politics.

Like Skocpol’s work, most research in this area examines policy influences on states and elites. But Pierson suggests that policy influences on mass publics, while understudied, are among the most important.11 He further asserts that they take two forms, material and cognitive. Indeed, the development of Social Security fulfills Pierson’s predictions about the influences policies might have on client groups. By conferring politically relevant resources, Social Security has had tremendous material effects, fundamentally enhancing seniors’ participatory capacity above what they could have achieved in the absence of the program. The program’s cognitive effects may be even more significant. Cognitive feedback effects provide otherwise scarce and costly information to individuals. According to Pierson, these cues “may influence individuals’ perceptions about what their interests are, whether their representatives are protecting those interests, who their allies might be, and what political strategies are promising.”12 Social Security’s cognitive effects have fostered senior interest in public affairs and enhanced their feelings of political efficacy as they achieved the notice of elected officials.

The political learning literature suggests an additional mechanism by which the cognitive effects operate—that the manner in which government policies treat clients instills lessons about groups’ privileges and rights as citizens. Policy design sends messages to clients about their worth as citizens, which in turn affects their orientations toward government and their political participation. Policy experiences convey to target populations self-images and outgroup images (who is “deserving” and who is not). Program recipients learn what actions are appropriate for their group. “Advantaged” groups like Social Security recipients consistently hear messages that they are “good, intelligent people” who have legitimate claims with the government.13 Social Security fosters seniors’ participation not only by enhancing their participatory capacity and giving them a compelling reason to pay attention to public affairs but also by affirming their rights as citizens to defend their benefits.

The profound effect of policy design on democratic citizenship is perhaps most evident with low-income seniors. Decades of participation research have shown that high-income individuals are more politically active. The income-participation gradient is particularly steep in the United States, which lacks lower-class mobilizing agents like leftist parties or strong unions. As we will see in chapter 3, however, low-income seniors are more likely than high-income seniors to participate with regard to Social Security. They are, for example, more likely to write a letter to a government official about the program, so that the usually positive relationship between income and participation is reversed. The difference in this policy area is that low-income seniors are more dependent on the program: Social Security makes up a larger share of their income, and so they are rationally more active. Furthermore, as a universal, non-means-tested program, Social Security includes low-income seniors in its “advantaged” recipient group. Unlike other low-income groups, poor seniors absorb from their policy experiences the same positive citizenship lessons their more affluent counterparts learn, including the message that defending their self-interests through political activity is legitimate.

Thus Social Security has implications for self-interest as a political motivation. The program ties seniors as citizens to state functions in an immediate way. Their engagement with public affairs is enhanced because their self-interest is so significantly and obviously implicated. Self-interest is seldom ...