eBook - ePub

The Contemporary Global Economy

A History since 1980

Alfred E. Eckes

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Contemporary Global Economy

A History since 1980

Alfred E. Eckes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Contemporary Global Economy provides a lively overview of recent turbulence in the world economy, focusing on the dynamics of globalization since the 1980s. It explains the main drivers of economic change and how we are able to discern their effects in the world today.

- A lucid and balanced survey, based on extensive research in data and documents, accessible to the non-specialist

- Written by a renowned specialist in international economic relations with academic and government credentials

- Offers clear and engaging explanations of the main motors of economic change and how we are able to discern their effects in the world today

- The author assumes little knowledge of economic theory or financial markets

- Identifies the challenges for sustainable recovery and economic growth in the years ahead

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Contemporary Global Economy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Contemporary Global Economy by Alfred E. Eckes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & International Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

At the beginning of the twenty-first century the typical resident of Western Europe, North America, or Oceania was increasingly cosmopolitan in consumption and outlook. He or she drove an imported car (perhaps German or Japanese), wore Chinese-made clothing, ate food products from various corners of the world as part of a daily diet, and communicated with an Asian-assembled computer or cell phone to friends or relatives all over the world. Internet e-mail, innovations like Skype, and Facebook, eased the way for exchanging information and images, and keeping up with a global network of friends and contacts. Those fortunate enough to have investment portfolios often diversified with foreign stocks or bonds. And residents of affluent nations thought little of vacationing abroad (France, Spain, North America, and China were popular destinations). Retirees opted for more leisurely travel, perhaps on one of the giant cruise ships that frequented Alaska or the Baltic in summer, or the Caribbean and Mediterranean in winter.

Four to five billion people joined the global market during the last quarter century. While local political and economic elites opted to hobnob with other elites, skiing at Davos in winter or yachting at St. Barts or Monaco in summer, many of the poor intersected the global economy differently. Some 500 million new factory workers – many of them young women – produced t-shirts, sneakers, iPhones and other products for export to consumers in other countries. Frequently, they labored 12-hour days, or longer, for low wages (perhaps the equivalent of $2 per day, or less), and had little leisure time. Many spent a portion of their meager earnings to enhance their mobility and connections to family and friends. Even in the most desolate locations, basic products like motor scooters, cell phones, and televisions expanded knowledge and widened opportunities. Hearing of better jobs in high-income countries, some entrusted their lives to professional smugglers who locked them in shipping containers, or led them on desert treks in the middle of the night, to cross borders. As millions of migrants had done in centuries past, they risked their lives to improve prospects for their families and themselves.1

While millions of people have benefitted from the contemporary global economy – particularly high-income and professional elites – not everyone has shared its prosperity. OECD studies show an increasingly skewed distribution of wealth in some countries.2 Jobless data indicate that factory workers, and their families, in high-income countries have experienced disruptions to their lives, as plants closed and jobs moved to countries with cheaper labor. In the Soviet Union, the collapse of state planning produced widespread hardship for pensioners and those unable to adapt to new circumstances. Others over-estimated their circumstances. They splurged, and took on risk and debt far in excess of their resources. As it turned out some of the greatest excesses were in government, where elected officials in many countries made fiscally irresponsible promises to win votes, and budget deficits soared.

In some ways the period from 1980 to 2010 was reminiscent of the late Victorian and Edwardian years before World War I. From about 1870 to 1914, the United Kingdom was the center of a similar world economy. It too was open to trade and finance, and imposed few restrictions on migration. As a result of submarine cables, news and information traveled rapidly. British-owned cables linked the world to London, and the Royal Navy protected maritime routes. Residents of the United Kingdom consumed the world’s products and invested their savings abroad in mines, ranches, railroads, and utilities. John Maynard Keynes, the famous British economist, recalled this extraordinary period nostalgically in The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1920). Keynes marveled at the “internationalization” of economic life, noting in a famous passage from his writings how an inhabitant of London could order by telephone, while sipping his morning tea, the various products of the whole world. He could invest his wealth in natural resources and new enterprises overseas, or buy the bonds of any substantial municipality on any continent that his fancy or information might recommend.3

But, alas, the open world economy that preceded World War I vanished in that conflict, as governments imposed controls to regulate economic affairs. For some 65 years until about 1980 national governments restricted trade and finance, controlled migration, and managed communications through government-owned or regulated monopolies. During this period two world wars, a great depression, and intense Cold War competition disrupted earlier economic patterns. But, late in the twentieth century when Cold War tensions subsided and enthusiasm for market forces revived, a new era of open markets and deregulation dawned.

Scope

This introductory chapter provides an overview of the extraordinary economic, political, and technological developments that shaped the contemporary global economy over the last generation. It considers the overarching themes, while the second chapter offers a short historical perspective on the early- and mid-twentieth-century international economy. The next two chapters examine how the broad themes of growth, integration, and volatility impacted the rich countries and the developing world. The fifth chapter discusses how ideas and individuals shaped the contemporary economy. Here we review the thoughts of Adam Smith and David Ricardo in the eighteenth century, and more recent business and economic thinkers like John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman, and Peter Drucker. Subsequent chapters consider how these themes apply to international trade, global business, and finance. Then the book revisits the recent global financial crisis, and examines the interplay of darker forces, including organized crime, trafficking, sweatshops, health and safety, and environmental issues. A concluding chapter surveys recent efforts to regulate and rebalance the global economy, and to engage rising powers.

The Contemporary Age of Globalization, 1980–2010

During the period from 1980 to 2008 the international economy experienced a second golden era, reminiscent of the peaceful prosperity before World War I. Despite a number of local and regional conflicts in the Falklands, the Balkans, Afghanistan, the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa, there were no overt hostilities among the great powers. Governments gradually cut taxes, deregulated markets, sold off state-owned enterprises, and dismantled trade barriers. During the 1990s they reduced arms spending sharply as the Cold War ended. The pace of change accelerated and transformed the political, social, and economic landscape. A variety of long-term trends and short-term conditions produced new opportunities for humankind, but also brought greater uncertainty, dislocations, and anxiety about modernization. On the one hand, there was greater integration of people and nations (globalization). On the other, there was resurgent localization (as ethnic groups sought greater self-determination and devolution of power) and protectionism, as afflicted groups challenged international efforts to knock down barriers and integrate markets. The meaning and implications of these terms will be addressed in subsequent chapters.

On the political front, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991 introduced an era of relatively peaceful co-existence among the great powers. Responding to new circumstances and ideas, governments around the world deregulated economies, privatized industries, and permitted market forces to revive. In encouraging deregulation and privatization Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and President Ronald Reagan led the way. Meanwhile, new technologies of transportation (wide-bodied jet aircraft and container ships), communications (cell phones, optic-fiber line, satellites), and information processing (personal computers), integrated national markets and dissolved border barriers.

For the global economy, these changes accelerated flows of information, goods, services, and money – and produced volatility as market forces responded to events. The world of the late twentieth century was no longer one in which ordinary people and communities were loosely connected by trade, occasional visitors, and sporadic information flows (an occasional telephone call or letter). The new world was immediate, interactive, and integrated. In the digital age information and ideas flowed at the push of a button. Retailers in one area of the world communicated electronically, and instantaneously, with suppliers thousands of miles away. Changes in commodity markets, exchange rates, stock prices, and interest rates impacted investors and producers in far corners of the world immediately. And large sums of private capital flowed easily and quickly from one region to another, challenging local authorities and regulators.

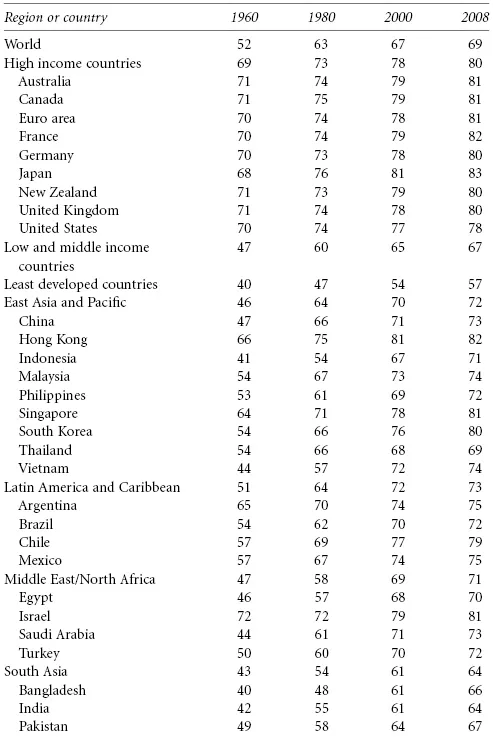

Life Expectancy and Literacy

During this period of economic restructuring, millions of people improved their own lives and living conditions. In most areas of the world, life expectancy increased. In 1960, a person born in a high-income country could expect to live to 69 years, 29 years more than a person born in one of the least-developed countries. By 1980, the gap had fallen to 26 years, the high-income country resident living 73 years, the least-developed country resident 47. Twenty-eight years later (2008), the last year for which data was available, the gap remained large at 23 years. Those born in a high-income country could look forward to 80 years of life; those in a least-developed country to 57 years. While an enormous gap remained, life expectations had expanded both in rich and poor countries with only a few exceptions. In sub-Saharan Africa, where AIDS took a heavy toll, nine countries had declining life expectations. They were Botswana, the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, Lesotho, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe, one of the world’s most mismanaged economies, experienced a decline of 15 years (from 59 to 44). In a few countries outside Africa, there were also declines in life expectancy: Kazakhstan, and the Ukraine, and North Korea.

Table 1.1 Life expectancy at birth (total years), 1960–2008

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators Database, http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog (accessed August 2010).

In the developing world of low- and middle-income countries, the literacy rate for adults ages 15 and above rose from 69.9 percent to 80.2 percent between 1990 and 2008.4

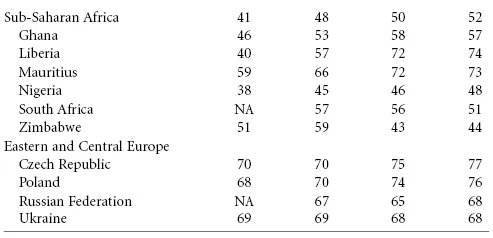

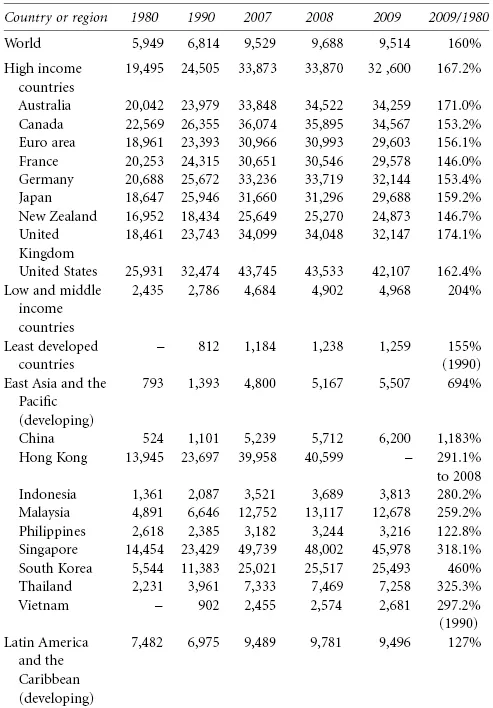

Improving Living Standards

Economic growth offered other evidence of improving conditions. During the late twentieth century, economic growth dramatically elevated living standards in many markets. Since 1980, the world’s gross domestic product (GDP) in constant dollars increased at a compounded rate of 2.8 percent annually. In developing economies GDP growth averaged an impressive 6.7 percent, but in older high-income countries the rate was closer to 2.5 percent.*

One of the better indicators of individual incomes is GDP per capita measured in constant dollars and using purchasing power parities to adjust for costs in different economies. For the world during the period 1980 to 2009 GDP per capita rose 60% from $5,949 in 1980 to $9,514 in 2009. The UK (74%) and the US (62%), had per capita GDP growth rate above the world average. But developing countries set the pace. In East Asia and the Pacific per capita GDP soared, rising 594% from 1980 to 2009. China enjoyed a 1,083% increase, followed by South Korea with 360%. India’s per capita GDP rose 230%. Such meteoric growth turned millions of peasants into consumers with cash to buy cell phones, televisions, and motorized transport, and to connect with the outside world. Rapid growth also created many new Asian millionaires. In 2009 it is estimated that individuals with at least $1 million of investable assets in Asia equaled the number in Europe and approached North America’s 3.1 million.5

In some areas of the world, per capita GDP growth was less spectacular. Remnants of the former Soviet Empire, undergoing the difficult transition from state-controlled to market-oriented economies, experienced uneven growth. Countries such as Poland and Slovakia, which attracted considerable foreign investment, did better than more remote locations. Russia managed a small gain – up 7 percent from 1990 to 2009. In the Middle East Turkey and Egypt experienced solid gains, as did the countries of South Asia. Latin America had uneven and sub-par growth, except for market-oriented Chile which turned in a superior performance. Sub-Saharan Africa was the laggard with GDP per capita climbing only 8 percent, but this region generated strong growth after 2000. A number of countries in that region experienced declining incomes. Some of them had unstable governments, wars and internal conflicts, and high-levels of corruption in the public sector.6

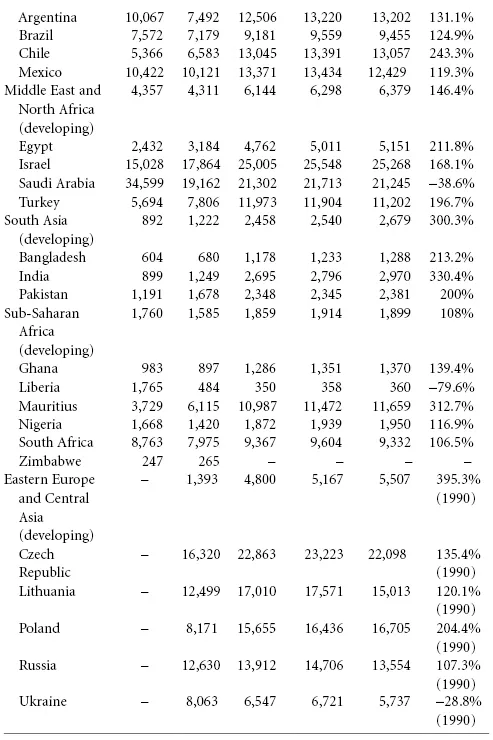

Table 1.2 Gross domestic product per capita (purchasing power parity, constant 2005 international $)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators, http://databank.worldbank.org/ (accessed October 2010).

Accelerating International Migration

People move across borders, as goods, money, and information do. During the period from 1980 to 2010, the flow of migrants accelerated. In 1980, nearly 100 million people lived outside their country of birth, 30 years later 214 million (3.1 percent of the world’s population) did. The trend was reminiscent of the first golden era of globalization (1870–1914) when governments imposed few barriers to migration and people moved freely. But two world wars, a great depression, and increasing immigration restrictions discouraged large-scale migration until the 1960s when governments began to relax restrictions. Some European governments began to recruit low-skilled labor in Turkey and North Africa. Over time former colon...