![]()

1

Formal and informal institutions of the socialist era

Lucie Coufalová1

The general intention of this part is to show the main characteristics of the environment in which the companies in the centrally planned system in Czechoslovakia operated. We describe the main features that constituted this environment. The chapter deals with the settings of the institutions (broadly a description of the socio-economic environment) in the socialist era. In specific, we describe the political development including the role of the Communist Party (1.1). Next, we concentrate on some aspects of the legal system and functioning of the judiciary in the country (1.2). In the following section, paternal-istic and repressive aspects of the state are analyzed (1.3) and the last section is dedicated to informal institutions – values in the society (1.4).

The socio-economic environment can be defined by institutions. We should distinguish between institutions that are understood as sets of rules (for example the legal system) and institutions in the form of organizations (for example the central bank or the planning commission). In this chapter, we pay attention only to the former. Economics treats institutions as “humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North 1990, p. 3). Rules make a person’s and government’s behaviour more predictable and in effect reduce uncertainty. Institutions are therefore something one needs to consider in the decision-making process. For example, low property rights protection and high risk of expropriation make people not invest in their businesses and rather pursue other investment objectives. The effects on social life are analogical. If trusting behaviour increases the chances of being punished – for example because of being reported by a colleague or a neighbour – people tend to reduce their far-reaching social ties and isolate themselves in their families (Boenisch and Schneider 2013).

Institutions are often divided into two subgroups: Formal and informal. Formal institutions are generally codified by an authority – the state – they involve those specified and enforced by the government; for example, the legal system or courts of law. Informal institutions are not defined by the state or enforced by the government but they are built in the society in the way of thinking and acting. These involve customs, morals, level of corruption and respect to the law. Informal institutions evolve spontaneously, they are more stable and change only over long periods (generations). On the contrary, the legal system can be changed relatively quickly.2

The mutual interaction between formal and informal institutions is complicated. People tend to behave according to informal institutions regardless of the formal ones. Or to put it in another way – even top-quality formal laws will not convince people to behave accordingly if they do not intend to abide. For example, the Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was legally perfect – it was a clear formal institution which prohibited production and sale of alcoholic beverages (valid between 1920 and 1933). However, it was also “a period of time in which even the average citizen broke the law” which made it the only case in the history of the USA when the Constitutional Amendment was repealed (Rosenberg 2017).

The specific impact of institutions on the economy is unclear but most economists believe that institutional environment is one of the key factors influencing a long-term ability to grow because institutional environment affects factor productivity or the long-term potential growth of the economy (see, e.g., North 1992). If there is, for example, low level of respect for the law, the costs of the functioning of the market subjects’ increase. This determines their profitability in the long run, and thus also investment and growth. Institutions are difficult to quantify or measure in general and therefore any attempt at measurement during the centrally planned economy (CPE) period was even more complicated. All in all, the state of both formal and informal institutions under socialist rule is generally seen as an obstacle for economic growth (see for example Tříska et al. 2002).

In the following text, we concentrate on the state and development of formal and informal institutions during the CPE period that affected functioning of the economy. They partly overlap, but we separate, among others, the political and legal systems, paternalistic state and behaviour of people (informal institutions) in this period.

1.1 Political system and development

The Czechoslovak political system after 1948 was totalitarian. We consider totalitarianism in accordance with Heywood as:

An all-encompassing system of political rule that is typically established by pervasive ideological manipulation and open terror and brutality. It differs from autocracy, authoritarianism and traditional dictatorship in that it seeks “total power” through the politicization of every aspect of social and personal existence. Totalitarianism thus implies the outright abolition of civil society: the abolition of “the private”.

(Heywood 2012, p. 207)

In Czechoslovakia, the basic concepts were authoritative governing, and enforcement of the pervasive communist ideology officially based on Marxism-Leninism.

Historically, the Communist Party was relatively strong already in pre-War Czechoslovakia. It gained around 10% of the votes in the interwar period and it was one of the strongest Communist parties in Europe at that time. This state was deepened by the political shift to the left that took place after World War II. This phenomenon appeared not only in Czechoslovakia but in several other countries as well – for example in Italy and France.3 It was, among other reasons, caused by admiration and gratitude towards the Soviet Union (SU). There were three main reasons for this attitude – the fact that the SU avoided the suffering of the Great Depression in the 1930s (due to the economy’s disconnection from the world markets), admiration for winning the war and gratitude for liberation of Czechoslovakia. The consequence of this political shift was that the Czechoslovak Communist Party won the first election in 1946 and gained 114 out of 300 seats in parliament. The Communists had the highest support in the Bohemia part of Czechoslovakia (see Table 1.1) and especially in the borderlands with Austria and Germany from where the ethnic Germans were expelled.4 From the total of 156 electoral districts in Bohemia and Moravia, the Communist Party won in 137 of them, and in the borderlands it reached absolute majority in 43 districts (Čapka and Lunerová 2012).

Table 1.1 Results of the first post–war election to the Czechoslovak Parliament (Ústavodárné Národní shromáždění), May 26,1946

| Communist Party |

|

| Bohemia | 43.25% |

| Moravia | 34.46% |

| Slovakia | 30.48% |

| Czechoslovak Republic | 40.17% |

Political competition by democratic parties was at that time already restricted because all legal political parties were associated in the so-called National Front (Národní Fronta) – a group of political parties with a monopoly on political power (see Box 1.1). Several political parties were not allowed to re-establish after World War II. Due to proportional settings of the electoral system in Czechoslovakia the Communists created a coalition government and they (and their allies) were able to control “power” ministries. The Ministry of the Interior as well as the Ministry of Information were held directly by the members of the Communist Party. The Ministry of National Defence was held by the war hero of the eastern front, general Ludvik Svoboda (in those days with no party affiliation), who only became a Communist Party member in 1948 and later on was elected president (1968–1975). This made it easier for the Communists to get the whole country under control following their coup in February 1948.

Box 1.1 The National Front

The National Front was established in April 1945 when the Czechoslovak government was created in the already liberated town of Košice in easternmost part of Slovakia. It consisted among others of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and the Communist Party of Slovakia, the Czechoslovak People’s Party (a form of a Christian-Democratic Party) and the Czechoslovak Social-Democratic Party. Several political parties were banned for alleged collaboration with the Germans – among others the Slovak People’s Party and the Republican Party of Farmers and Peasants. The National Front was dominated by socialist parties foremost the Communists. Competition among political parties was thus limited. Later on (in the 1970s and the 1980s) the Front co-opted many other specific (and sometimes even obscure) organizations (e.g., the Czech Union of Beekeepers).

The political regime in the following years was extremely harsh. There were political processes, executions, and people were sentenced to long imprisonment in de facto concentration camps. The first emigration wave took place as well. This situation slightly relaxed only after Stalin’s death in 1953. Klement Gottwald, the long-standing leader of the Czechoslovak Communist Party since 1929 and perpetrator of the February coup, died just 10 days after his Bolshevik mentor Stalin when he had returned from Stalin’s funeral in Moscow.

The role of other authorized political parties during the whole period was only formal and their goal was to pretend political pluralism. In fact, their practical influence was minimal. In reality, the National Front was fully subordinated to the needs of the Communist Party and any competition among the political subjects was unthinkable. Political freedoms in Czechoslovakia did not exist. The regime tried to increase its legitimacy by extremely high voter turnout at parliamentary elections (see Table 1.2).

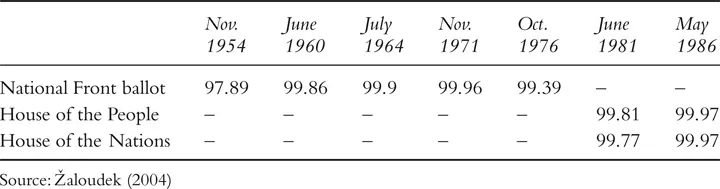

Table 1.2 Voter turnover in Czechoslovakia, 1954–1986 (in %)

The voters were presented with a single list of the National Front pre-approved candidates – in reality, there was just one candidate on the list. It meant that the voters could just approve or disapprove the candidate of the National Front. At the same time, taking part in the election was compulsory, and the citizens had little chance to avoid voting should they want to express their dissatisfaction with the regime this way. It was difficult even to put blank ballots into ballot boxes because going behind the divider was considered as an expression of informal disapproval with the regime. Quite to the contrary, manifestation voting was supported by the regime (see Box 1.2). Regardless of the non-existence of choice, the regime pretended that it held real elections.

Box 1.2 Practice of communist exercise of law

The communist legislation after the implementation of the Socialist Constitution of 1960 was formally very similar to the legislation of any democratic state. The Election A...