![]()

1 Gender, space and development

An introduction to concepts and debates

Sandra Huning, Tanja Mölders and Barbara Zibell

Introduction

Talking about gender, space and development involves exploring inter- and transdisciplinary fields of research and practice which have developed in their particular settings over time and are characterised by different, and at times contradictory, concepts and debates. Specific national trajectories of the women’s movements as well as particular planning cultures and systems have had an important impact on the ways in which the concepts and debates around gender, space and development have been framed, adapted and developed in different national contexts (see Chapter 2). Some concepts have travelled across national or regional borders in the Western world and, at first sight, have helped to establish a common understanding among researchers and practitioners. However, the different ways in which such concepts have been employed and embedded in their respective environments make it necessary to re-engage with terminology, professional understandings and socio-cultural, -economic and -political settings to enable cross-European communication with regard to these issues.

This chapter aims to provide an overview of concepts and debates in the European context with a focus on commonalities and recent developments. As three German researchers, we recognise that it is unavoidable that we argue from our own “partial perspective” (see Haraway, 1988), which is shaped by a necessarily limited range of literature, discourses and our particular fields of expertise (spatial science, sustainability science, urbanism and spatial planning). With kind support from our colleagues from North, West and South European countries, we intend to broaden this perspective, while acknowledging that there is a much broader global debate that we will not be able to consider. We do not intend to give definite answers and universal definitions, but instead to show a range of concepts and debates which have proved fruitful for the discussion, can be used in various settings, and are in many cases further considered in later chapters of this volume. Thus, this introduction seeks to fulfil a heuristic function for the following chapters with regard to the categories of gender, space and (spatial) development – including spatial planning – and also with regard to sustainable spatial development as a shared analytic and normative orientation.

Ever since the 1992 Rio declaration, sustainability has been recognised worldwide as a key principle for bringing together environmental and development issues. In order to achieve intra- and intergenerational justice, sustainability means respecting the reproductive requirements of natural resources and attributes a strong role to the participation of women – including the fight against discrimination. Thus, gender perspectives in sustainable development involve both strengthening women within the discourse and pursuing a feminist critique of the discourse (see the last section “Sustainable spatial development – integrating concepts and debates”). Translated into spatial development, the sustainability principle serves not only as a normative guideline that gives orientation to politicians and professionals, but is also regulated by planning legislation and other legal obligations at different territorial levels. Therefore, sustainable spatial development is not only an option but an obligation and responsibility of stakeholders. At the same time, gender equality, equity and justice1 are much more than optional in development and planning. At both the supranational and national level, especially in the European context, gender concerns and gender justice are to be incorporated into every political programme, plan and measurement. One example is the adoption of the gender mainstreaming principle in 1999 (European Communities, 1997).

This chapter is organised along the three categories that we consider essential for our discussion. Attention is first directed towards the category of gender (the first section). For decades, feminist scholars and practitioners have engaged in a debate that has developed from the assumption of biologically distinct women and men to the notion of gender as a social construction. In order to systematise diverse analytic perspectives, and to match the theoretical and empirical diversity within gender studies and spatial politics, we introduce approaches and differentiations which appear to us to be promising with regard to spatial development. The second relevant category is space (the second section). Spatial sciences traditionally assumed space to be simply given, without much reflection (cf. in Germany the critiques by Sturm, 2000), often understood as surface or territory (geography, spatial planning), or as a container (architecture and urbanism), insofar following an adapted understanding of the ancient world. In the course of the so-called “spatial turn” of the 1980s, space became a central category in social sciences and humanities (notably in sociology and history). Here space is no longer an abstract dimension, but a category exploring relations and (contingent) interpretations. Thus, space is an entity that provides economic, environmental and social living conditions, a notion which underlies this book. The third important category is spatial development as a field of action and governance among politics, planning, economics and people (the third section). Here the category gender becomes relevant with regard to both theory and practice (the fourth section). In this context, the political strategy of gender mainstreaming is also crucial for the concept of gender planning as “gender mainstreaming in spatial planning”, but it is certainly not the only path towards gender recognition in planning. Summarising our findings, we focus on sustainable development as a critical concept and transformative project, which allows the nexus of gender, space and (spatial) development to be addressed from a feminist perspective (the fifth section). Thus, we argue that the normative ideal and legal objective of sustainable development must include gender as a key category of societal factors. Sustainable development also connects gender aspects and spatial development both through gender equality and equity requirements (which will be explained in more detail below) and the need to integrate different social, environmental and economic requirements. We claim that in pursuit of sustainable spatial development, gender-oriented concepts challenge today’s hegemonic rationalities, question current modes of allocating socio-spatial resources and require the inclusion of marginalised target groups. These critical perspectives are directly linked with visions of alternative economic concepts and ideals of democracy, and their spatial realisation in new forms of housing, the design of public spaces and other spatial plans and development.

Gender

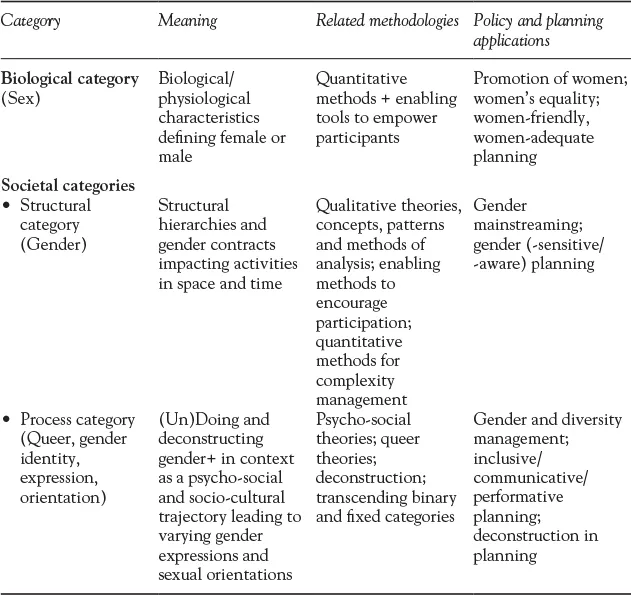

The aim of this book is to look at spatial development from a gender perspective. We argue that the category of gender is of central significance for an understanding and evaluation of spatial structures and processes. Gender perspectives may function as epistemological approaches aiming to make the relevance and scope of gender visible. In recognition of the manifold attempts and proposals to systematise gender approaches in theory and practice (e.g. Harding’s 1991 classification of feminist schools of epistemology, Keller’s 1995 differentiation for science studies “women in science”, “science of gender”, “gender in science”), we follow a differentiation of analytic perspectives developed by Sabine Hofmeister, Christine Katz and Tanja Mölders with regard to the gender and sustainability nexus (Hofmeister, Katz and Mölders, 2013; see also Hofmeister and Katz, 2011). To further systematise gender-related concepts and debates we classify the analytic perspectives by distinguishing one biological and two societal gender categories. These perspectives are based on distinctive understandings of the category gender, reflecting the history of women’s and gender studies and exploring the theoretical and practical added-value of each particular viewpoint. Each gender category is related to specific methodologies aiming to understand and operationalise the particular perspective. Finally, each gender category tends to correspond to selected policy applications addressing a different gender perspective (see Table 1.1).

Biological category

Gender as a biological category addresses women and men as two different and distinguishable sexes. This understanding marks the starting point of a women’s studies research approach which was informed by feminist movements and women’s policy of the 1970s and 1980s. The declared aim of this kind of analysis is to make the inequality and discrimination of women, as a clearly distinguishable collective subject, visible and criticisable. A great advantage of this perspective for both theory and practice is its compatibility with much empirical work, for data can be disaggregated concerning male and female individuals according to their own or others’ categorisations. However, the conceptualisation of gender as a biological category of difference has been criticised as essentialist, assuming a biological gender identity and homogeneity of “men” and “women” as collective groups that does not exist.

Table 1.1 Analytic categories of gender with related methodologies and applications

Source: based on Hofmeister, Katz and Mölders, 2013; Horelli and Wallin, 2013; Roberts, 2013.

Societal category

Gender as a societal category tries to overcome the individual and essentialist perspective while emphasising the social construction and societal embeddedness of gender. Consequently, gender perspectives address gender relations in their historical, societal and cultural context. While some European languages differentiate between a biological sex (Spanish: sexo, French: sexe) and a social gender (Spanish: género, French: genre) others do not (e.g. German or Finnish) and therefore use the English term gender to signify the latter. Within the variety of gender approaches the question of how far materiality (still) exists – for example with regard to a biological sex – is crucial and heavily discussed (see for old and new feminist materialism Bauhardt, 2017). Moreover, one may differentiate between perspectives focusing on gender as a structural category and those which address the process of (un)doing gender.

Structural category

Gender as a structural category focuses on the configurations and conditions leading to the appreciation and devaluation of gendered fields of work, social positions, etc. (Aulenbacher, 2008). Critique of the separation and hierarchisation of a productive (male) and a reproductive (female) sphere outlines a key discussion within this understanding. In addition, there are other dichotomous patterns which are directly linked to the gendered separation of production versus reproduction (e.g. public versus private, paid versus unpaid work). Furthermore, it is acknowledged that gender is one, but not the only, category structuring society. Research on intersectionality focuses on the nexus of these societal structural categories (Crenshaw, 1989; Knapp, 2005; see below), and debates on “gender and diversity” or “gender+” broaden the perspective with regard to categories such as “race”, “class”, “age”, etc.

Process category

Another shift within gender studies is marked by an understanding of gender as a process category. Based on the assumption that neither sex nor gender are fixed categories, gender as a process category opens up a perspective which inquires into the interactive (co)production of gender, “doing gender” (West and Zimmerman, 1987; Butler, 2004; Gildemeister, 2008). It can be linked to approaches focusing on the dimensions of gender identity, gender expression and (sexual) orientation, their interaction and disruption. From a poststructuralist point of view, queer theories not only address the construction of (gender or sexual) identities, but are also interested in “how norms and categories are deployed” (Oswin, 2008: 96). From this point of view, they criticise standardisation and homogenisation (Engel, 2005). This kind of looking for the in-betweens (e.g. naturecultures (Haraway, 2003), (re)productivity (Biesecker and Hofmeister, 2010)) seems to be inspiring for theoretical reflections as well as for interventions and disruption in practice.

In sum, researchers and practitioners are confronted with a variety of gender concepts and perspectives. All of these perspectives are informed by particular understandings of the category gender that are not always properly distinguished or distinguishable. Current debates about gender and its implementation in theory and practice strive to consider its linkages to other categories of marginalisation and discrimination in order to prevent its becoming invisible as a key category of social analysis. In this ambiguous and tense field, debates on diversity are often criticised for diminishing the category gender to only one of many categories that need to be taken into account. As the diversity concept is frequently linked to business strategies aiming to maximise the economic success of companies, it may lose the critical intention of gender approaches that include a questioning of affirmative capitalist economic orientations. The feminist academic debate on intersectionality makes it clear that such a limited gender perspective has to be overcome in order to look critically at relations of power and domination. By investigating intersections of different categories of marginalisation and discrimination, intersectionality addresses societal structures as a whole, but remains strongly linked to women’s and gender studies where it has become a new paradigm (Winker and Degele, 2009). It is important in all these debates to remember that not only gender, but also categories such as “race” or “class” must not be understood in essentialist ways, rather their social construction needs to be constantly considered. In order to take up these discussions and to underline the crucial significance that the category gender still has, new concepts such as gender+ (Alsos, Ljungren and Hytti, 2013) aim to conceptualise gender as a social category complemented by and linked to these other socially constructed categories.

Space

Space is another important concept in the context of this volume, and can simultaneously serve as another epistemological category. In spatial planning and spatial sciences, it has been – and continues to be – conceptualised in manifold ways. Spatial c...