eBook - ePub

Culture and Change Along the Blue Nile

Courts, Markets, And Strategies For Development

Lina Fruzzetti

This is a test

Share book

- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Culture and Change Along the Blue Nile

Courts, Markets, And Strategies For Development

Lina Fruzzetti

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book aims to bring a concern with cultural values and meanings closer to the study of the economic, political, jural, and religious change and development in the Sudan. It concentrates on sections of Sudanese society caught in the rapid changes of the 1970's.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Culture and Change Along the Blue Nile an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Culture and Change Along the Blue Nile by Lina Fruzzetti in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Sudan, the Blue Nile, and the Question of Development

Positioned half way between the Arab and the African worlds, the Sudan is made up of numerous and diverse social groups and cultures. Long a home to indigenous chiefdoms, kingships, and sultanates, in the early 19th century the Sudan came under foreign domination: Turkish, Egyptian, and then British. After the defeat of the Mahdi, the great Islamic warrior-saint who attempted in the late 19th century to integrate diverse societies into a theocratic state, the entire country came under British rule. The British, in an effort to pay for the administration of the country, decided to develop agriculture. Several economic development projects were started by them, some of which have continued into the present. A model for future agricultural progress was established in 1905 when the colonial administration set up the Gezira Scheme. The British realized that the Sudan, though economically poor, was a country with great potential. Land was plentiful, the waters of the two Niles could be used for irrigation, but the country lacked sufficient capital for development. The Sudan achieved independence in 1956 and since then the expansion of the agricultural sector has accelerated. Most large projects designed or implemented in recent years have been funded and supervised by foreign agencies, such as the World Bank, the United States Agency for International Development and other development agencies from Europe and from Arab oil-producing countries.

The Sudan is the largest counry in Africa covering about 2.5 million square kilometers. It is sparsely populated except along the White and Blue Nile rivers and their tributaries. The majority of the 17 million inhabitants, subsistence cultivators and pastoralists, live in the rural area. Even though these two forms of livelihood exist side by side and often overlap, agriculture clearly dominates the economy. Beside providing a living for 80% of the population, since pastoralists also cultivate some farmland, agriculture contributes about 40% of the GNP and 95% of exports. Internally also the Sudan's economy depends on agriculture rather than pastoralism. But the renewed emphasis on agriculture has resulted in serious clashes between the two ways of life: as more land is brought under cultivation, the available pasture lands diminish. With even greater investment in agricultural development today, this sector will continue to dominate the economy.

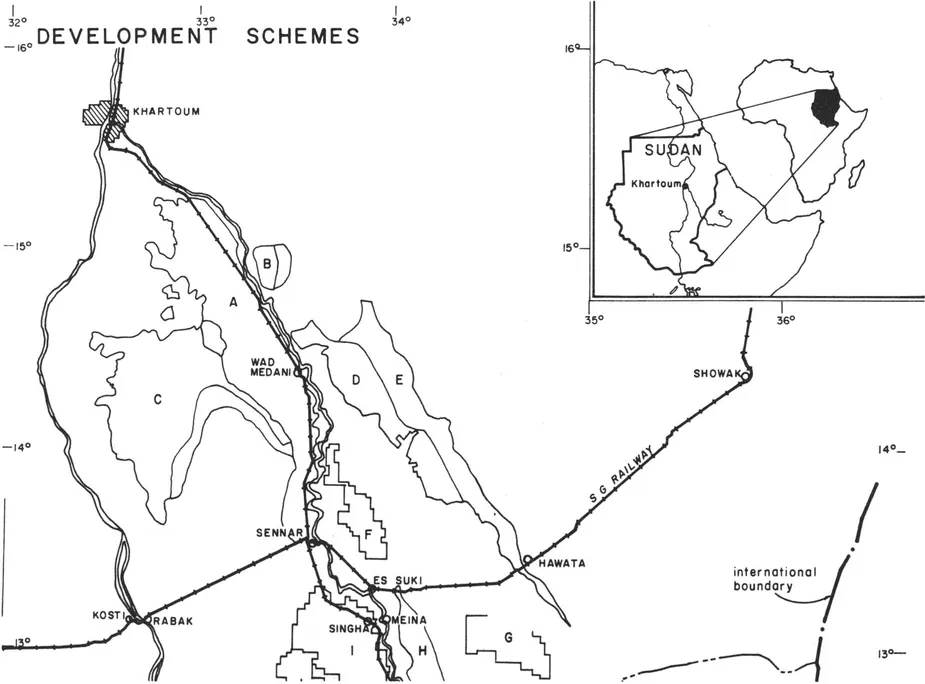

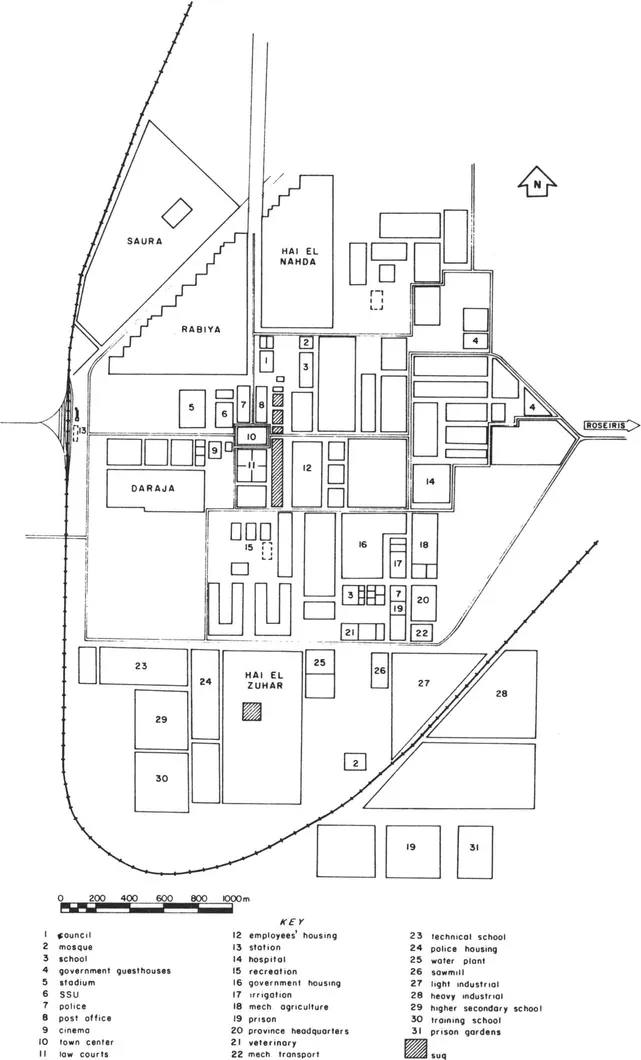

What distinguishes Sudan's agriculture is the peculiar, local coexistence of a dual system: a modern mechanized and/or irrigated, and a traditional, subsistence sector of farming.1 The former sector, based on the use of the Nile waters, is characterized by large scale, mostly state owned, partially or completely mechanized irrigation or rainland projects aiming at the production of cash crops such as cotton and sesame by modernizing the techniques of farming and expanding the area under cultivation. Irrigation costs are very high ranging from $2,000 to $5,000 and in some cases up to $10,000 per hectare not including government services which may add another $100 to $400 per hectare. (See Figure 1.1).

The traditional sector, mostly in private hands, receives little or no assistance from the state and very little technical aid to improve farming methods. It comprises rainfed subsistence agriculture. Rainland farms are usually small and poorly managed. As a result, production from these farms only suffices for the consumption needs of individual families. In the last few years the use of mechanized pumps along the White and Blue Niles has been increasing on private farms and gardens, whereas the larger pump schemes are government owned.

Though at present most large irrigated farms are state owned there is a tradition of irrigation in the private sector. At the turn of the century, modern gravity and pump irrigation replaced traditional flood irrigation, shadouf (irrigation by buckets) and sagia (water wheels), which were used up to that time extensively and successfully. The change in irrigation techniques necessitated the building of large and expensive dams and reservoirs to store the water. Over the last fifty years the Sudan has been able to irrigate 4 million feddans through reservoirs. Most of these irrigated farm lands are along the Blue and White Niles and use as their model the system of management and irrigation of the Gezira scheme. Away from the two Niles one finds a prevalence of small subsistence farms. This is also the case for the Western and Southern parts of the country where rainland farming and rainfed agriculture predominate. The kind of crops grown also differ in the modern and traditional agricultural sectors. The produce of irrigated farms is mainly for export while subsistence farms have taken care of domestic consumption. Irrigated farms grow cotton, groundnuts and wheat, while traditional farms cultivate sorghum, millet, sesame and wheat.

Post-independence regimes and states in the Sudan have committed themselves to certain kinds of modernization and directed change, and over the last few years the pace of development has increased dramatically. There is considerable concern on the part of government, universities, research institutes and the public at large with the rapidity and extent of change as well as the possible erosion of Sudanese values and ways of life. One shared expectation is that it should be possible to articulate economic development with the culture and values of Sudanese societies within the framework of a nation state. Following the resolution of a long and destructive civil war in the South in 1972, the government has embarked on an ambitious and expensive program of development. But by the mid 1980's the civil war resumed in the South, the development effort was near breaking down, and the military government collapsed. From its inception the new civilian regime has been confronted with major economic and social dislocations issuing from war, ethnic and religious conflicts, famine, and desertification, yet it remains committed to economic development and cultural change.

Aims of the Study

The argument of the book is that law, markets, and administration constitute, in part, the culture of development; ignoring these would lead to a lopsided view of social change. It is a commonplace that the societies which actually experience change themselves should be studied in order to understand the changes affecting them. But not only are villagers in project areas "societies," so are the people participating in markets, offices, and law courts. They also constitute a system of relationships with a parallel system of cultural categories, meanings and values. Our detailed narrative should reveal the complex interrelations of law, market, schemes and administration. We describe the social situation of large scale development schemes and smaller scale agricultural projects. All development efforts are doomed to fail unless local cultural and social contexts are fully integrated into the stages of planning and implementation. A cultural account can deal with aspects of development left untouched by the variety of economic approaches we criticize (modernization and dependency included). Even when these approaches do consider cultural phenomena they require the latter to be a separate and additional "input," secondary and inferior to economics and politics. Hence we discuss development in the context of market and exchange relations; civil and people's courts of law; administration and politics; projects, schemes and village social organization; and we attempt to find the links among these seemingly disparate parts that add up to, in our view, the totality we have to comprehend.

A more indirect aim of the book is to bring a concern with cultural values and meanings closer to the study of the economic, political, jural, and religious change and development in the Sudan. Having done extensive research in India, we came to study Sudanese societies utilizing the theoretical and methodological approaches we have developed in our previous work, with the eventual aim of arriving at a comparative understanding of continuity and change in South Asia and Africa. This wider perspective involves a dual attempt to generate anthropological theory from a comparison of societies analyzed and understood in terms of their own cultural categories and symbolic meanings, and to bring the

Figure 1.1 Development Schemes Along the Blue Nile

anthropologist's fine microstudy and cultural understanding to bear on the problems and dislocations of change and development experienced by South Asian and African societies today.

We hope that this work is a first step towards our goals. It is neither an ethnography nor a development report in the conventional senses of these terms. It is a study of development in which specific anthropological concerns are brought to the examination and evaluation of actual development processes. It is an account of the problems of the development effort and an examination of the affected social groups such as merchants, officials, farmers, women, and pastoralists. It is also a criticism of general approaches to modernization and development which have become, by now, the ideological staple of politicans, experts, donor agencies, and officials both Sudanese and non-Sudanese.

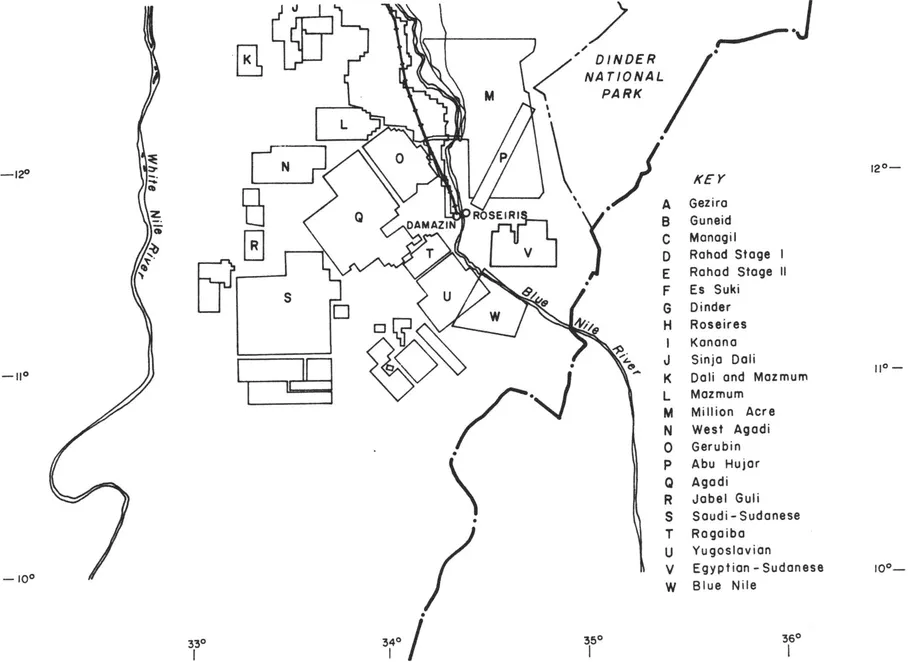

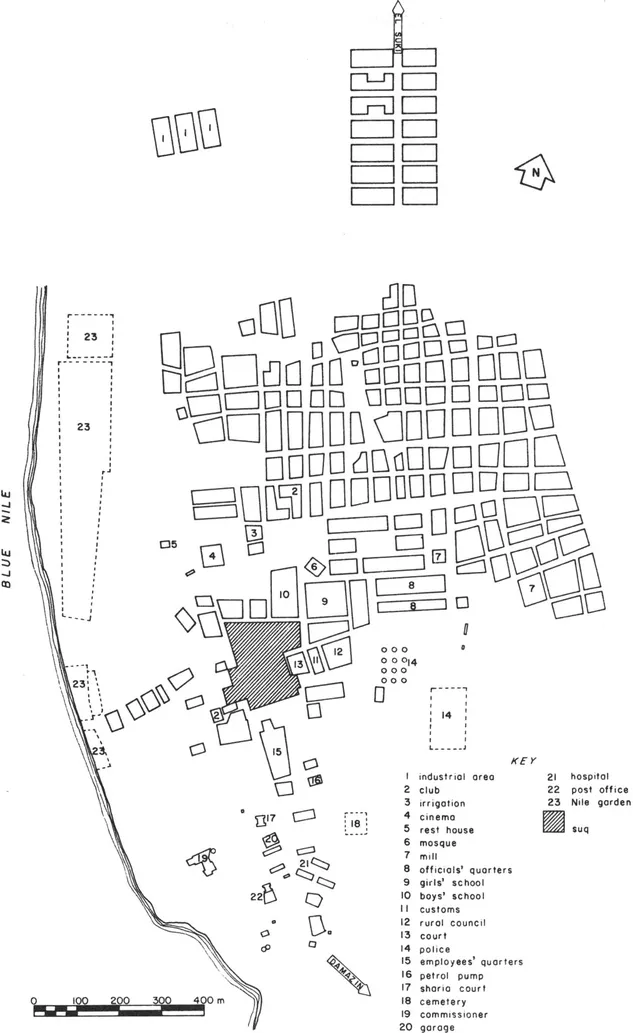

We studied aspects of change in two small towns and a region in the Blue Nile Province. The towns lie on opposite sides of the Blue Nile River which has been dammed at this point to provide irrigation and electric power. Roseiris, is the older town, while Damazin, a new town, is the center of regional administration and of many development projects. (See Figures 1.2 and 1.3). The 1955/56 census lists about 4,000 people for Roseiris, Damazin having been included in the rural area. By the 1964-66 household survey Roseiris stood at 7,300 and Damazin at 7,600, with an additional 1,400 as the "institutional population" of Damazin. The figures for the 1973 Census have both towns at about 12,000 people.

In the early 1970's several mechanized agricultural projects have been started outside the two towns, with investment from Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Sudan. Other agro-industrial projects were started in the late 1970's with American, Yugoslav, and German collaboration. To the south, there are mining concerns with Chinese, Japanese and American involvement. Damazin is the center for all these projects, most of which draw on local labor in tenant farming. This extraordinary effort however is taking place in the midst of a rural society in which widely different modes of living have been successfully articulated, although not without conflict, over the last few hundred years. Some specific things are happening to this articulation today.

Given that Sudanese society is changing, what does change mean, in what context and for whom? Will indigenous culture and values continue to express meaning for people and groups in social relations, and can they transform the potentially corrosive changes brought by development and modernizing efforts without being obliterated by them? What is the probability of avoiding the destructive imposition of outside models for change? Is there any chance of achieving national economic and political goals within the framework of Sudan's unique combination of African and Islamic civilizations and the indigenous cultural values of smaller scale societies? We do not believe that there are simple, overall answers to these questions. Ours will be given in a disaggregated form, in terms of the patterns and meanings we find in markets, law courts, villages, offices and development schemes.

Figure 1.2 Map of El Roseiris

Figure 1.3 Map of El Damazin

Except for applied anthropologists most anthropologists have shied away from considering the problems of the societies they study. Applied anthropology on the other hand has been narrow in its approach to small scale problem solving, ignoring in the process the unique strength of anthropology: its holistic, totalizing, cultural perspective on society. It is this strength anthropology should contribute now in order to ease the disruption caused by rapid change and to participate in the search for indigenous values in approaches to development.

On a general theoretical level, we would argue for a more direct application of cultural approaches to the study of change. Too often the different aspects of social relations are left to the different methods and subfields of the social sciences in general and anthropology in particular. Economic, applied, political and cultural "anthropologies" proliferate and address different issues and audiences as if they were dealing with separate realities. Overarching approaches are not brought to bear on problems of economy and polity, while structure is thought of as underlying and not belonging to the domain of change, except to the extent traditional structures and values either hinder or ought to be rescued from change. Thus studies of culture, values, social structure, economic and political development remain divergent, each fitting into a neat typological niche. Yet an integrated study of all these aspects of society in the one locality is a precondition for understanding rapidly changing societies. One way out is to focus on change itself and posit some discontinuity between old and new, traditional and modern, past and present. Yet at precisely this point the endeavor can be questioned on the basis of a cultural approach: what are the categories chosen to reveal the contrast between these dichotomies? Do they really reveal change? Is change just posited on the basis of an extraneous universal framework or sociological theory? Another option is the study of values: the determination of new or modernizing values and the concomitent identification of traditional values. These approaches lead to filling out typologies rather than to an understanding of the actual changes that are taking place in particular societies or of the fundamental as against surface nature of these changes. Similarly, social structural studies alone are too static and synchronic to reveal the extent of change. On the other hand, diachronic approaches (inspired to a greater or lesser extent by rather self-absorbed Marxist methods) often cannot account for structural continuities and find difficulty in encompassing the cultural element as well as the moment of change from one kind or type of social formation to another. All these difficulties can be transcended to a degree by studying the relationship between culture, values, and social structure in a given context.

"Culture," in our view, is a system of symbols and meanings in society which may also provide the categories for the interpretation of social relations in indigenous terms. "Value" stands for indigenous construction of preferred, desirable and worthwhile ends in social action, relation, and being. "Structure" refers to the nature of the relationships among cultural categories and units in society, exhibiting properties of continuity, transformation, reciprocity, and replacement. The operations identifying the relationship between culture, values and structure within the context of an actually functioning society are crucial to successful development. The alternative is to intuit traditional and modern values independently of ideas and practices in given societies.

This book concentrates on sections of Sudanese society caught in the rapid changes of the 1970's. It gives case studies, each as complete as possible, of the cross-cutting factors and patterns present in the lives of local people. The rest of this chapter gives the historical background and the contemporary social situation of the Blue Nile region. Having taken a brief look at urban and rural groups, history, courts, markets, nomads and the problematic role of anthropology in development, we go on to criticize modernization and dependency theories which have become, by now, the twin bane of development studies. Neither approach is capable of giving a satisfactory account nor point a way out of the current impasse for countries like the Sudan. Chapter 2 is a study of Damazin/Roseiris townships, mainly through the marketplace (suq) and through the links between merchants, officials and development. We also discuss the impact of the Roseiris dam on the surrounding rural area. Chapter 3 is a study of women in agricultural schemes: the silent and neglected partners in development who nevertheless bear the brunt of change, both planned and unintended. Chapter 4 is a study of law courts, with special attention to the conflicts brought about by social change and migration. Chapter 5, written by Dr. Mahgoub El Tigani Mahmud, is a study of administration, politics and development on the national and local levels. It reveals a cultural system in the midst of a bureaucratic society. Various conflicts arise out of the difficult and contradictory demands placed on administrators. Chapter 6 is a case study of research in development: the ambiguous example of the Blue Nile Integrated Agricultural Development Project. Chapter 7 is a detailed survey of the major mechanized and irrigated agricultural schemes of the Sudan. The Gezira, Managil Extension, Rahad, Es Suki and the Guneid sugar schemes are examined in their structure and organization, as well as the position of their tenants. The last chapter presents the conclusions and implications of the study.

Historical and Societal Contexts

In the 17th and 18th centuries the region of our study was a part of the indigenous Funj Sultanate. Funj rule disintegrated in the wake of the Turkish invasion in 1820. During British colonial times the area to the West has been settled by West Africans, who came to the Sudan on their way to perform the haj (pilgrimage to Mecca). The indigenous inhabitants are still living around Roseiris and Damazin. Although little is known about them, recent work is beginning to document their societies. They have been a part of larger polities in the past. Coupled with relatively autonomous kinship - marriag...