The Russian Land

Most Americans, even those accustomed to the transcontinental stretch of their own country, find it difficult to comprehend the vast expanse of territory encompassed in the Russian state, known formally as the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). To be sure, we learn such numbing facts as that the Soviet Union covers one-sixth the land surface of the entire earth, or that Russia has literally stretched, at least since the late 1600s, all across Eurasia from “sea to shining sea,” from the Pacific Ocean on its eastern border to the Baltic Sea, an arm of the Atlantic Ocean, on its western boundary (see Map 1). But it requires a specific experience to make concrete the enormous sweep of the Russian land.

For me this happened one evening in the 1960s when I boarded a train to travel from Kiev, an ancient city in the southwestern republic of the Ukraine, to Moscow, the old and present capital of the country in central western Russia. I would travel only overnight, but I found occupying at least 80 percent of the space in the Pullman compartment I had been assigned a large and voluble Soviet woman (sleeping cars on Russian trains traditionally accommodate both sexes) accompanied by what seemed like a hundred suitcases, bundles, packages, and even a small trunk. Friendly conversation soon revealed that her husband was a colonel in the Soviet air force stationed in Vladivostok, a main port and base on the Pacific Ocean. She had been home visiting relatives in the Ukraine and had stocked up on a few supplies to make her life on the distant frontier of the Soviet Far East a bit more comfortable. As I tried to wedge myself in among the boxes and bags, I asked her how long a trip she would have. When she replied, “Eight nights and seven days,” my jaw dropped and I stared at her. Seeing my surprise, she admonished me, “Yes, it is a big country, much bigger than yours.” (And, in fact, bigger than the United States and Canada combined.)

Six thousand miles and eleven time zones from east to west, three thousand miles from north to south, with the world’s longest coastline (much of it on the frozen Arctic Ocean), the Soviet Union has every sort of terrain: desert, semitropical beaches and fruit groves, inland seas, sweeping semiarid plains, rugged mountains, fertile treeless agricultural fields (the famous steppe), thick forests, long rivers, and the ice-locked tundra of the far north.

Russia’s size alone, now as the Soviet Union and for over two hundred years before the Communist Revolution of 1917 as the Russian Empire, has created special challenges for the people living there. How is such a huge territory to be managed and its riches extracted and used efficiently? How can its inhabitants stay in touch with one another and develop a sense of common identity and purpose? How can power be exercised and the state administered over such vast distances? These problems, which plagued the Russian tsars, still vex the Soviet leaders today. What should be the balance between control from the center and local decision making? Should new industry be developed where a majority of the people live but where there are few resources, or where there are lots of raw materials but few inhabitants? How can diverse peoples, so widely scattered, have a common belief, or even agree on what language all should speak?

In addition, the great extent of the Russian land mass has had important strategic consequences. Paradoxically, Russia has been both hard to conquer and hard to defend. Today Soviet generals worry about a possible two-front war, against the United States and its allies on the Soviet Union’s western border and against the People’s Republic of China in the east. Earlier, the Russians had, at various times, to cope with enemies on three, four, and occasionally even five fronts. Thus, the Russian government has always had to allocate much of its effort and resources to defending its large territories. On the other hand, Russia’s opponents have had trouble invading and occupying the country. Although the Mongols succeeded in conquering and ruling most of Russia from the 1200s to the 1400s, the Poles, the Swedes, the Turks, the French under Napoleon, and the Germans, twice in the twentieth century, have had less luck, being turned back in part by the enormous distances to be traversed.

In assessing the influence of Russia’s natural environment on its history, its location is as important as its size. For example, if you lived in Washington, D.C., and were suddenly transported by magic to a city in the Soviet Union with a comparable location, where do you think you would end up: Moscow? Kiev? Not at all; you would miss the Soviet Union entirely because it is located so far north in Eurasia that most of the country lies in latitudes parallel to those of Canada and Alaska. Leningrad, for example, is just a bit farther north than Juneau, Alaska.

This northerly position on the earth’s surface has caused recurring hardships for Russia’s citizens. In most of the country, winters are long and cold, and the growing season for food is short. Besides, much of Russia’s huge territory is so far north that it can’t be farmed, and living there is unpleasant and expensive. One result has been that Russia has never been rich agriculturally, despite its huge size.

Although situated in the northern part of the great Eurasian land mass, the Soviet Union stretches south, east and west so that it touches most of continental Asia, the Middle East, and Europe (see Map 1). Consequently it has always been a crossroads of cultures and ideas. Russia has been affected by European, Asian, and Islamic civilizations and has absorbed something from all of them. In turn, and increasingly in the past two hundred years, it has influenced and, on occasion, dominated its neighbors.

In the 1930s an elaborate theory of “geopolitics” concluded that Russia was ideally located to rule the world. Although such a notion is clearly rubbish, there is no doubt that the central location of the country in Eurasia has contributed strongly to the mix of cultures and values in it today and to its important role in contemporary world affairs. Even though it is linked to both Asia and the West, Russian society has evolved in distinct and complex ways. It need not be characterized as exotic, Asian, or “Mongol”; nor should it be interpreted as a stunted offshoot of western civilization. It has had a unique history that has produced a modern society unlike any other. The Soviet Union must be understood on its own terms.

Without venturing into geographical detail, we need also to note the effects on Russia’s historical development of several topographical features of the Russian land. Partly because of its northerly location and partly because it is situated far from the major oceans, Russia has a forbidding climate in most regions: very hot and dry in the summer, and bitterly cold in the winter, with a spring marked by deep mud that makes travel on unpaved roads almost impossible. Since most of the rain comes across Europe from the Atlantic Ocean, it peters out as it moves over the Russian agricultural plain from west to east. Some of the best soil receives insufficient rainfall, and almost all the farming in Soviet Central Asia requires irrigation. The result is that less than 15 percent of Russia’s land is used for growing food, another feature that limits the country’s agricultural potential and strength.

The borders of the Soviet Union have contradictory characteristics. In the north the country is well protected by the frozen expanse of the Arctic Ocean and in the southeast by some of the highest mountains in the world (see Map 1). Modern bombers and missiles have made these barriers obsolete, but it is still true that to invade Russia from either of those directions would be almost impossible. On the other hand, along its borders in the east, the southwest, and the west Russia has virtually no natural defenses, and at different times it has suffered invasions from all those points of the compass.

Moreover, the heart of the country is one vast plain, broken only

by the Ural Mountains, which are not very high and which in any case do not reach all the way to the Caspian Sea. The effect of this plain has also been two-edged. Russia has been open to attack across this terrain, but the extent of the plain has made it easy for Russians, and the Russian state, to expand and to bring surrounding nationalities under Russian rule. Thus, when I flew for the first time from Moscow to Tashkent in Soviet Central Asia, looking down hour after hour at the endless semidesert, or when I took the train from Czechoslovakia to Moscow and gazed for almost two days across rolling Russian steppe, I could easily visualize Asian horsemen, Russian traders, and modern armies moving back and forth across the flat expanses.

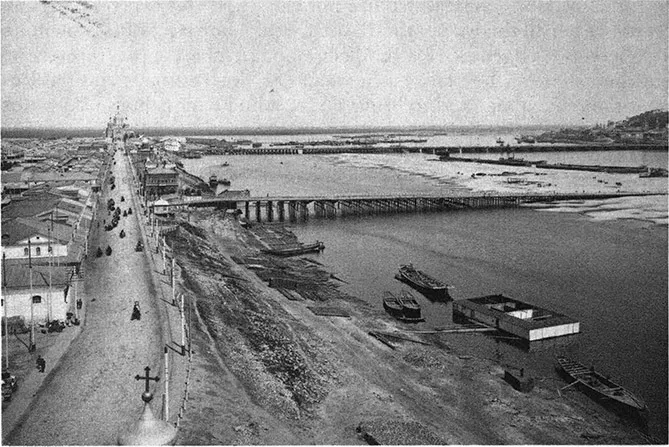

But Russians have historically traveled as much by water as by land. Although the country is largely landlocked and has limited access to the sea—the Arctic shore opens primarily on ice, and the Baltic and Black seas and the Sea of Japan in the Far East lead to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans only through narrow straits subject to closure by enemy military action—Russia possesses a widespread system of interconnecting rivers, “the roads that run,” as folk wisdom puts it. Up to the last one hundred years, when railroads, motor vehicles, and planes appeared, Russians moved extensively by boat, up and down the rivers, which generally flow in a north-south or south-north direction, or along the tributaries that touch each other along an east-west axis. Thus, the earliest inhabitants, using river routes, traveled to and traded with Europeans and Vikings in the northwest, Greek Christians of Byzantium in the southwest, and Asian merchants and artisans in the south. Later, Russia’s expansion across Siberia, led by fur trappers and traders, was carried out primarily by water. Even in modern times river transport has played an important role in moving goods and people throughout the country (see Figure 1).

The contemporary Soviet Union is rich in natural resources, in fact virtually self-sufficient, despite a recent dependence on imports of grain. But much of this wealth, such as oil, natural gas, and other abundant minerals, has been exploited only recently. Historically, Russia has been a very poor country, its people struggling to survive and improve their way of life while supporting, with limited resources, a government-organized defense against recurrent enemies. Unfortunately, carrying the burden of the state and the army has too often meant that the people have lived in harsh poverty. Recently, progress in raising the quality of life has been made, and the resources exist for Soviet citizens to live more comfortably in the future.

Nevertheless, problems remain. Much of Russia’s wealth, as in the past, is being eaten up in defense expenditures. The economy, now as often before, is sapped by inefficiencies and irrationalities. A major dilemma is that the most important and abundant natural resources are in the eastern part of the country, where the fewest people live and where the climate is generally inhospitable. It is expensive to transport these raw materials to factories in western Russia, where the bulk of the population lives. On the other hand, it is unlikely that many people, even with attractive material inducements, will be persuaded to move to Siberia.

Figure 1. Barge traffic in the 1890s on the Volga River, an important commercial artery in Russia from earliest times.

Finally, the Soviet Union confronts, as Russia did throughout its history, a major problem of food supply. Crop yields, especially per capita, have always been low. In the past this has meant a constant battle to survive and a coercive pattern of economic, social, and political institutions in society. Today, it is a brake on the further development of the Soviet economy and creates an unwanted dependence on foreign imports. Much of the Soviet Union’s poor agricultural performance can be explained by such natural factors as limited arable land, inadequate rainfall, and a short growing season. But low agricultural productivity also stems in part from the lack of incentives for farmers and from the organization of agriculture under Soviet socialism. Whether this can be changed remains, as we will see in Chapter 13, a moot question.