![]()

1

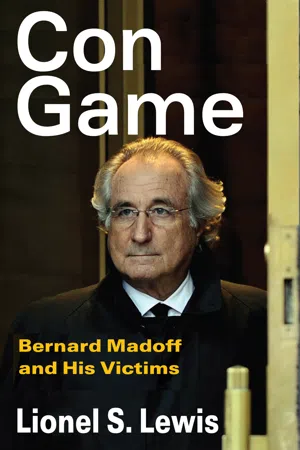

The Victims and Their Day in Court

And there was a little man sitting behind a very big desk. “Are you Mr. Madoff?” I asked. “Yes, and I’m expecting you,” he said, his mouth pursed in what was his trademark smirk.

—Carmen Dell’Orefice, Supermodel

Bernard L. Madoff was arrested in December 2008 for defrauding thousands of individuals and organizations of billions of dollars for over two decades. The part of Madoff’s investment advisory company involved in private-investment or asset-management was where all of his illicit activities were carried out.1 In fact, most employees had no idea he was stealing from his clients. Madoff had perpetrated an outsized Ponzi scheme, a Brobdingnagian con game.2

In March 2009, Madoff pleaded guilty of soliciting funds to buy securities and failing to invest the money. He used the money instead, as did the notorious Charles Ponzi, to pay returns to early investors and for his own benefit. According to the initial reports of the office of the U.S. Attorney, at the end of November 2008, Madoff’s investment advisory company reported that they held a balance of $64.8 billion. A government press release from the day he was arrested stated Madoff himself “estimated the losses from this fraud to be at least approximately $50 billion.”

Three months after his arrest, government attorneys still had not determined the total number of Madoff’s victims and the amount of money they lost. As an early press release concluded: “There are thousands of potential victims in this case; thousands of additional potential victims who have not yet been identified by the government, and no readily available compilation of such individuals and entities. . . .” Even at the time of Madoff’s sentencing, the judge noted that because of “the number of victims, the difficulties posed by the lack of proper record-keeping, and the scope, complexity, and duration of the fraud,” it was difficult to arrive at reliable numbers.

In the months following Madoff’s arrest, various figures released by the government constantly changed. For example, shortly after Madoff’s arrest, federal prosecutors were able to show that total net losses for approximately 1,341 accounts in which investments were first made between December 1995 and December 2008, were $13.2 billion. In late March 2011, there were 16,269 total determined claims submitted to the government by bilked investors. Whatever the numbers, the global reach of Madoff’s swindle was enormous: individuals and institutions from over 40 countries, 339 funds of funds, and 59 management companies were invested with him. The list included the following: from Europe—Swiss private banks, an Italian bank holding company, old wealth from England, France, and Monaco, and Dutch money managers; from Asia—Japanese banks and insurance companies, a Singapore insurance company, and Hong Kong trust funds; and wealthy families from Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. There were also sovereign wealth funds from the Middle East.

Madoff’s swindle has been extensively covered in the media, and much has been learned about his early childhood and young adulthood, his career, his lifestyle, his family, his friends, and how he duped so many. There are many accounts of how he succeeded as long as he did, more accurately of how journalists with more skill at crafting stories than gathering information assumed how he operated.3

Just as others who have had long-running Ponzi schemes, Madoff relied on word-of-mouth and social networks to find investors. Some found out about him from their accountants, from their brokers, from their dentists, from golf or bridge partners, and from relatives. He, and those who solicited funds for him (ropers), often did not rely only on business settings, but also on social settings to find people to steal from. They found investors through friends, in country clubs and yacht clubs, and at ski resorts in the United States and around the world, and in service and religious organizations.4 As in the case with Charles Ponzi, what we know about the effects of what Madoff did is mostly about the substantial financial damage. We know a lot less about the victims, and the impact of their losses on their lives, and what they did after Madoff’s fraud was revealed. The aftermath of Madoff’s crime is the primary subject of this study.

A PBS documentary on Madoff after he was arrested, for example, gave virtually no attention to the victims beyond brief profiles of four cases seemingly chosen because of what the media call compelling stories: the former mayor of Fort Lee, New Jersey, who lost $5 million investing directly with Madoff and in a feeder fund that sent money to Madoff; a law school dean, who suggested on his blog, a government conspiracy in the matter; most ironically, a retired employee of Merrill Lynch, who, not surprisingly, was repeatedly interviewed by the press across the country; and a couple in their middle seventies, whose account of losing 85 percent of their life savings is overshadowed by their revealing that their ophthalmologist and his network of thirty-three family and friends had been “wiped out.” It is from this last case that the seriousness of Madoff’s crime might be most fully understood—instead of a comfortable retirement, the wealth of an entire family (grandparents, parents, and children) was lost, and with indigence following. Indeed, it was found that the loss of multigenerational wealth was what most upset many of those Madoff victims who were part of this study.

The most obvious reason we know so little about white-collar crime(“a crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his [sic] occupation”) and its victims is that results seem less disturbing than those of violent crime—a corpse from a homicide, a mangled automobile after an intoxicated driver failed to heed a red light, a photograph of a terrified and bruised housewife beaten by a burglar or spouse. On the other hand, it is often difficult to put a face on the businesses, organizations, or the general public injured by the most common white-collar crimes—embezzlement, fraud, graft, illegal combinations in restraint of trade, misrepresentation in advertising, infringement of patents, adulteration of food and drugs, or bribery.

In the study of criminal behavior, social scientists have neglected white-collar crime and focused almost entirely on street crime and delinquency. The “captains of industry” who led the United States into the Industrial Revolution after the Civil War used bribery, kickbacks, and dubious financial schemes to acquire massive fortunes, but were called to account by few other than the radical left and muckrakers, after which they were renamed “robber barons.”

Of course, if not much is known about white-collar crime, not much will be known about its victims. In the study of the victims of crime, in the last four or five decades, a great deal has been learned about the victims of street crime, but next to nothing is known about the victims of white-collar crime, although the economic and human costs of the latter dwarf those of the former. Indeed, both the Uniform Crime Report and the National Crime Victimization Survey—jointly used in the formulation of public policy—are concerned almost entirely with street crime. Yet, as has been repeatedly shown since the publication of Edwin H. Sutherland’s exposition on white-collar crime in 1949, its consequences can be devastating not only economically, but also psychologically.5

Still, it is easily forgotten that after a white-collar crime is uncovered, when victims learn that they are in fact victims, the tale is far from over. There is still a great deal more to the story, well beyond assessing costs or losses. Of course, not all victims of white-collar crime attempt to seek redress for their losses, but there are any number of ways to do so, perhaps the largest and most visible number resorting to the law. This chapter focuses on investors who lost money in Madoff’s crime and who became involved in the legal process.

I first describe who these individuals are and how their financial losses affected their lives. I then examine their efforts—in their own words—to make sure their victimhood is fully understood. For this, Madoff’s sentencing trial is revisited as it not only provides more details about these swindled investors, but also because the court is the public forum where those who violate the law often officially receive new and negative social identities, something Madoff’s victims hoped would be given to him.

The foundation of this chapter is an analysis of the universe of 167 written statements submitted to the court inUnited States of America v. Bernard L. Madoffby his victims prior to his plea (29) and his sentencing (138). (Actually, more than these 167 victim impact statements were submitted to the court, but those too brief to provide more than a few pieces of useful information were put aside early in the study.) Of the total written statements used, slightly over half are petitions to the judge requesting that Madoff not be shown leniency. Another forty-seven are from the “Ponzi Victims Coalition”—individuals primarily from Colorado—to the presiding judge, federal prosecutor, and the U.S. Senate Finance Committee, who, among other things, request assistance in obtaining restitution for monetary losses. An additional two dozen ask for the right to speak to the court and a handful offer suggestions about a variety of issues, for example, determining an appropriate plea or setting adequate bail.6

Some submissions are co-authored and some are written on behalf of a family member, in a number of instances those too old or despondent to write. Some individuals expressed themselves in half a page; others filled almost four single-spaced pages. The purpose of the victim impact statement, as specified by the courts, is that it “allows victims to personalize the crime and express the impact it has had on them and their families,” which in this case the great majority of them did quite well. They allow those who see themselves harmed to express the degree to which they wish to see an offender punished. The victim impact statement can be more germane in a case like Madoff’s, where an offender pleads guilty and avoids a trial, than when there are not multiple victims or when there is cross examination, where the offense and the offender’s responsibilities are more completely examined.

For our purposes, the victim impact statements permit us to more fully understand criminal activity by studying how those who see themselves as injured view the criminal, the crime, and their relationship to one or both, even if what they report might in fact be somewhat distorted. (In fact, some who submitted statements to the court are not truly victims in that they withdrew more from their accounts than they invested with Madoff. Some surely are exaggerating the extent of their losses and victimization.)

A twenty-six-item coding schema was developed so that there would be uniformity in explicating the statement of each individual. There were many missing values; in fact, no submission provided information for all twenty-six items, and only a few came anywhere close to doing so.

The fact that these individuals publicly expressed their grievances, while the overwhelming majority of Madoff’s victims did not avail themselves of this opportunity, makes it impossible to claim that these 167 individuals are representative of those defrauded by Madoff. It is probably the case that victims who felt publicly shamed or victims with a sense of entitlement were more likely to write victim impact statements than those who readily accepted their fate, or who took a different path to express themselves, or not express themselves at all. In short, these Madoff victims could well be a biased subset of victims and not a cross section, but they are diverse, suggesting that they are not merely malcontents or cranks. Not all are married. Obviously, all were well-off enough to invest, but not all were wealthy. Certainly, not all were retired in Florida, California, Colorado, or Arizona, as was suggested by some media. Grandmothers, grandfathers, daughters, sons, and grandchildren wrote victim impact statements. There were no celebrities or individuals of great wealth among this sample; as with the whole of Madoff’s victims, there were retired businessmen and professionals who lost their retirement accounts, not multimillionaires who lost their third or fourth vacation homes.

Of course, the overwhelming majority of financial risks in Madoff’s theft were not to individuals or families, but to organizations, primarily financial ones. These organizations, from a half dozen different European countries, were Banco Santander (a Spanish bank), exposed for $2.87 billion; Bank Medici (an Austrian bank), exposed for $2.1 billion; Fortis (a Dutch bank), exposed for $1.35 billion; HSBC (a British bank), exposed for $1 billion; Union Bancaire Privée (a Swiss bank), exposed for $700 million; and Natixis SA (a French investment bank), exposed for $554.4 million.7 This list reminds us that it would be an oversimplification to dismiss Madoff’s victims too quickly as merely naïve investors whose greed blinded them to obvious folly, although, as subsequent chapters will show, greed was certainly not absent in a number of cases.8

After Madoff’s arrest, a number of investment advisors expressed the belief that those who invested with him “chose faith over evidence.” One described a meeting he had with Madoff in 1997 in which he “found him stylistically like a lot of traders: fast-talking, distracted, and not remarkable.” He added, during their two-hour meeting: “there was one red flag after another.” To him, it was evident that Madoff was “a con man.”

The Victims of Con Men

Although perhaps in this instance meant as irony, the reference to Madoff as a con man reveals an essential truth about him and provides a lens through which to view him, his Ponzi scheme, and his victims. In fact, looking at Madoff as a con man, what he did as a variation of a con, and his clients as victims of a con greatly increases our understanding of how he so dexterously stole their money and to their reaction to being fleeced. Con games are carefully staged charades, and that is surely what Madoff was engaged in.

The general elements of the con game are readily recognizable in Madoff’s Ponzi scheme. (1) Well-off victims were found. (2) Their confidence was gained. (3) They were roped by ropers to the inside man (Madoff). (4) Victims were told that they could make a considerable amount of money. In the lingo of con men, they were told “the tale.” (5) Victims could readily see how they were making money; their monthly statements were used as “convincers” to show them how their investments were steadily growing. (6) Victims were fleeced, the intention of all con games.

The term con game is, of course, a misnomer. Individuals are not engaged in a game of chance where there are odds, where they have even a slim chance of winning. Someone has set out to cheat them, to steal their money—at a fixed contest at a carnival, at the table of a “Three-card Monte” dealer on a street corner, or in a Ponzi scheme.

Oftentimes, obviously, marks are not necessarily innocent victims. The relationship between con men and marks is generally collaborative. Sometimes, in fact, the mark, not the con man, can do the hustling. Nobody has described the process better than Herman Melville:

“Thank you, thank you, my good sir,” said the other, receiving the volume, and was resuming his retreat, when the merchant spoke: “Excuse me, but are you not in some way connected with the—the Coal Company I have heard of?”

“There is more than one Coal Company that may be heard of, my good sir,” smiled the other, pausing with an expression of painful impatience, disinterestedly mastered.

“But you are connected with one in particular—the ‘Black Rapids,’ are you not?”

“How did you find that out?”

“Well, sir, I have heard rather tempting information of your company.”

“Who is your informant, pray,” somewhat coldly.

“A–a person by the name of Ringman.”

Don’t know him. But doubtless, there are plenty who know our Company, whom our Company does not know; in the same way that one may know an individual, yet be unknown to him. Known this Ringman long? Old friend, I suppose. But pardon, I must leave you.”

“Stay sir, that—that stock.”

“Stock?”

“Yes,it’s a little irregular, perhaps, but—”

“Dear me, you don’t think of doing any business with me, do you? In my official capacity, I have not been authenticated to you. This transfer-book now,” holding it up as to bring the...