1 Shareholder power as a major cause of excessive risk-taking in banks and other financial institutions

The principal aim of this chapter is to illustrate that the standard UK corporate law and governance framework – which applied to banks and other financial institutions nearly unmodified, until the introduction of a series of reforms after the 2007–2009 financial crisis – is prone to undermine financial stability.1 Indeed, it will be shown that the pursuit of profit maximisation inevitably entails taking a level of risk that, even if it is totally desirable from the point of view of diversified financial institution shareholders, tends to be excessive from the perspective of society as a whole, due to the systemic consequences of the failure or distress of any major financial institution. This claim will be further supported by exploring available empirical evidence on the relationship between shareholder power and risk-taking in financial institutions. Thus, a level of risk that is optimal for financial institution shareholders is likely to be excessive from the perspective of the public interest. For the purposes of this chapter, it is assumed that financial stability is a public good and that increasing the insolvency risk of one financial institution undermines financial stability, while further analysis on this matter will be deferred to Chapter 3, which sets out the development of the prudential regulation framework in the UK.

The second aim of the chapter is to demonstrate that the externalities problem described above is materially exacerbated by the limited potential of market discipline – both by the equity and debt capital markets – to curb excessive risk-taking by financial institutions. Of course, the less-than-perfect operation of market-based governance mechanisms is not a phenomenon exclusive to the financial sector and many of the problems identified in this chapter affect all large public companies.2 However, the opacity of financial assets and the acute information asymmetries involved, combined with the moral hazard effect of expected state intervention in case of systemic institution failures, make these problems far more serious in the case of the financial sector. The outcome of this is that financial institution senior managers are – in the standard case – free to take even more risk than perfectly informed shareholders and creditors would allow, to their detriment and to the additional detriment of financial stability.

The chapter is structured as follows. Section I illustrates that – theoretically – rational diversified shareholders often stand to gain from an increase in the investee company’s insolvency risk and thus that on certain occasions the private interests of financial institution shareholders will clash with the public interest in financial stability. Section II complements the above finding by reviewing empirical evidence that confirms the existence of a positive correlation between shareholder power and insolvency risk in banks and other financial institutions and identifies the ways in which shareholder preferences are channelled into executive decision-making via the design of remuneration contracts. Then, section III demonstrates that shareholder monitoring of risk-taking in the financial sector tends to be ineffective, thus allowing senior managers to take even more risk than fully informed shareholders would accept. Section IV engages with evidence regarding risk monitoring by financial institution creditors, that is depositors and bondholders, and reaches a similar conclusion. Section V concludes by bringing together the two strands of the discussion in this chapter, arguing that reduced market discipline exacerbates the inherent misalignment between the optimal level of risk for diversified financial institution shareholders and the level of risk that is acceptable in the public interest.

I. The divergence between the optimal level of risk in the interests of rational diversified financial institution shareholders, and in the public interest

This section demonstrates the inevitable misalignment between, on the one hand, the collective private interests of diversified shareholders, and on the other, the public interest in financial stability.3 As a preliminary point, it is necessary to explain the concept of risk, as used in the present discussion. Economists draw a clear distinction between risk and uncertainty.4 There is risk when the future is unknown, but the probability distribution of possible outcomes is known. The best example of that is a fair dice or casino gambling. Conversely, there is uncertainty when we do not know the future and when the probability distribution of possible outcomes is unknown. Almost all business activities entail a degree of uncertainty. Take the example of a bank advancing a personal loan to a customer. It is not known whether the customer will repay the loan, nor what the probability is that he will repay the loan in full and in time. Of course, the bank in question will estimate the probability of the loan being duly repaid based on historical data and on certain assumptions about the type of customer. However, this estimation is a subjective opinion on the probability of repayment, and is not necessarily correct, as the true probability of repayment is – strictly speaking – unknown. It follows that whenever there is uncertainty there is also potential for divergence of opinions between different parties with regard to the probability of a future event.5 In the above example, there is no single definitive way for banks to calculate the probability of loan default, different models leading to different results.6 It is evident thus that financial institutions, as other businesses, face uncertainties rather than (known) risks and therefore that using the term risk is somewhat inaccurate. However, given the conventional usage of the term risk to include uncertainty in legal and regulatory literature, I will use the term risk in this manner, although what is meant is really uncertainty.

The attitude of different persons to risk is different. In the case of a known probability distribution, we can define as risk-neutral any individual who is indifferent to the risk and makes decisions based on the expected value of the outcome. Using the dice example, a risk-neutral person will be indifferent between being given £10 or having the chance to win £60 if he correctly predicts the outcome of a fair dice. A risk-averse person will prefer being given £10, and will demand more than £60 to take the chance. How much more a person would demand to choose a risky outcome instead of a risk-free one depends on one’s degree of risk aversion. On the contrary, a risk-preferring person will prefer to be given the chance to win £60 rather than to be given £10. A risk-preferring individual may actually accept to bet even if the possible gain was less than £60, depending on his risk appetite. Of course, the same person may be in some contexts risk-averse and in others risk-preferring. However, empirical evidence shows that individuals are generally risk-averse,7 while the degree of risk aversion varies dependent on demographic characteristics.8

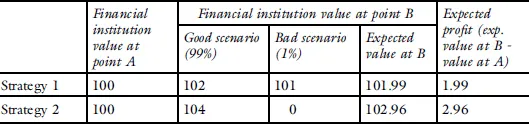

Generally, rational dispersed shareholders prefer the corporate strategy with the highest risk-adjusted return, even if it engenders a risk to the company’s survival, as they tend to be risk-neutral. This is because the vast majority of shareholders in the UK are institutional investors9 with fully diversified portfolios.10 In other words, they have no financial interest in the preservation of any particular company as a goal in itself, but rather view investee companies as vehicles to maximise the economic returns on their investment. Table 1.1 provides an illustration of the point that in some cases it is efficient for rational shareholders of a financial institution to prefer a business strategy with a high net risk-adjusted value, which, however, may lead to the failure of the institution. All figures are hypothetical. They show a financial institution’s expected financial value, after two alternative strategic options (a conservative and an aggressive one) have been implemented at point B in time. The initial value of the financial institution is 100 (at point A in time). In both cases, there is a good scenario (99% probability of happening) and a bad scenario (1% probability of happening).

The expected value of the financial institution at point B is the average of the risk-adjusted values in the good and bad scenarios. For strategy 1, this is (99% x 102) + (1% x 101), which equals 100.98 + 1.01 = 101.99. The expected profit is 101.99 – 100 = 1.99. For Strategy 2, this is (99% x 104) + (1% x 0), which equals 102.96 + 0 = 102.96. Therefore, the expected profit is 102.96 – 100 = 2.96. This example illustrates the evident point that limited liability combined with risk neutrality means that it is in the interest of fully diversified shareholders to follow corporate strategies that are likely to lead to very high profits but carry a small risk of causing the institution to fail. Of course, this is the case in all companies with dispersed shareholders,11 and not only in financial institutions. What is special in the case of financial institutions is that, given the far-reaching consequences of their failure on the financial system and the economy as a whole, questions of public interest arise.

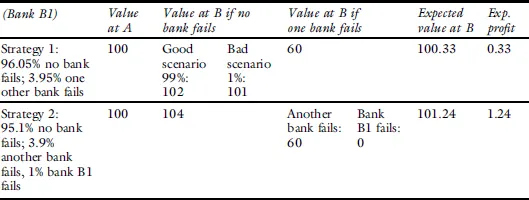

So far, the discussion analysed shareholders’ incentives ignoring systemic risk. The following discussion takes systemic risk into account. Suppose that there are five systemic financial institutions with a value of 100 each and that all of them can follow either the prudent Strategy 1 or the risky Strategy 2, with the same expected returns as in Table 1.1. As before, there is a good scenario and a bad scenario. The difference is that if any of the five financial institutions fails, the others will suffer a decrease of their value by 40% (hypothetical figure).12 If no other institution fails, the expected value of each institution is as in Table 1.1. Table 1.2 illustrates the incentives of the shareholders of one of the five systemic institutions (Bank B1) if they assume that all other institutions will follow the risky strategy and thus that each other bank has a 1% chance of failure within the relevant time period. If any other institution fails, the value of Bank B1 will be 60 irrespective of the strategy it followed, unless B1 itself fails. If, however, no other institution fails the value of Bank B1 will depend on which strategy it followed and on whether it was successful or not (i.e. whether the good or the bad scenario materialises).

Table 1.1 Shareholders’ incentives (disregarding systemic risk)

Table 1.2 Shareholders’ incentives (factoring systemic risk)

If bank B1 follows the safe strategy, there is no risk that it may fail. As we assumed that the other four institutions will follow the risky strategy, each of them has a 1% chance of failure. Thus, the chance that any of the four will fail is 3.95%. This includes the very unlikely cases (less than 1 in 10,000) that more than one institution will fail, but these cases are excluded from the table. It follows that there is a 96.05% chance that no bank will fail, if B1 follows the prudent strategy. If Strategy 1 is followed, and no other institution fails, then the probability distribution and outcomes are the same as in Table 1.1. If Bank B1 follows the risky strategy there is a higher chance that one of the five institutions may fail, as there is a 1% probability that B1 may fail. Then, the chance that at least one of the five institutions fails during the relevant time is 4.9% (3.9% another institution fails + 1% B1 fails). It follows that the chance that no institution fails is (under Strategy 2) 95.1%.

The expected value of B1 at point B is calculated as follows. For Strategy 1, it is the sum of the case where no other institution fails and the case that one other institution fails. If no institution fails, the expected value of B1 is (99% x 102) + (1% x 101), which amounts to 101.99. If one other institution fails, the expected value of B1 is 60. The total expected value of B1 is therefore (96.05% x 101.99) + (3.95% x 60), which is equal to 97.96 + 2.37 = 100.33. For Strategy 2, it is the sum of three cases: the case that no institution fails, the case that one other institution fails and the case that B1 itself fails. If no institution fails, the expected value of B1 is: 95.1% x 104 = 98.9. If one other fails, it is: 3.9% x 60 = 2.34. If B1 fails, it is 0. Overall, the expected value of B1 under Strategy 2 is: 98.9 + 2.34 + 0 = 101.24.

We observe that once the consideration that all other institutions will take a similarly high level of risk and hence another institution may fail is taken into account, the shareholders of bank B1 face an even stronger incentive to take the risky option than under Table 1.2, where we calculated their incentives in isolation of the rest of the financial system. In isolation, the risky strategy is approximately 50% more profitable than the prudent strategy. However, once the risk that another systemic institution may fail during the following year is taken into account, the risky strategy leads to an expected profit of 1.24, while the prudent only to 0.33, i.e. the risky strategy is four times more rewarding. This is due to the fact that the risk that another institution fails is not dependent on whether bank B1 follows the risky or the prudent strategy. In other words, financial stability is a public good, in the sense that no individual institution has an incentive to ‘produce’ it, as will be discussed in Chapter 3.

Finally, Table 1.3 illustrates how the aforementioned incentive structure can destroy value in the financial sector by comparing the total value of the five institutions in our hypothetical financial system in two cases: first, the case that all follow Strategy 1; and second, the case that all follow Strategy 2. All figures come from Tables 1.1 and 1.2.13 If all institutions follow the prudent strategy there is no risk that any institution will fail and the expected value of the system at point B is the sum of the expected values of each institution (from Table 1.1), that is 509.95. If all institutions follow the risky strategy, the...