![]()

1

The Labour Party in crisis – an overview

The Labour Party is in serious trouble, and faces a series of crises greater than it has experienced since the 1930s. The faction fighting of recent years over the party constitution and policy are only visible indicators of underlying problems which go deep, and which have been with the party for many years. There are three major crises facing the party at the present time which stand out particularly. Firstly, there is an ideological crisis manifest in the battles over the constitution, the split with the Social Democrats and the problems of entryism from the revolutionary Left. Secondly, there is an electoral crisis manifest in the long-term decline in the Labour vote, producing a vote share of 28.3 per cent at the 1983 General Election, the worst result since 1918. Thirdly, there is the less conspicuous but nevertheless damaging decline in the individual membership of the party, the component of total membership not tied to trade union affiliations. This can be described as the membership crisis, which in turn has produced major financial problems plunging the party deeper and deeper into debt.

These three crises, together with the debilitating problem of finance, put the future of the party at risk as the main alternative party of government. Any organization which faces multiple crises will at some stage reach a point of no return, at which the problems become so great that it can never overcome them. This has not already happened to the Labour Party, and it is certainly not inevitable that it will happen. But we shall argue in this book that it could easily happen if nothing is done to reverse the decline.

The main thesis of this book is that these interrelated crises all have a common origin in the failure of the Labour Party, particularly in office, to achieve its goals. Failures of policy performance are at the heart of the crises of the Labour Party. The party shares in the wider failure of British institutions, and British society, particularly in the field of economic management. But we shall argue that the party has made a considerable contribution to these failures, and this ultimately explains its present travails. In saying this, we must recognize that the Conservative Party shares in this failure, particularly since 1979, together with the other major institutions of government, such as the civil service, Parliament, industry and finance, and the trade unions. But our theme is not the decline of Britain, a subject ably discussed elsewhere (Alt, 1979; Gamble, 1981). Rather our focus is on the role of the Labour Party in that decline, and the consequences of that role for the party.

At the centre of the analysis is the implicit notion that the Labour Party is just a key component of the wider political system, which in turn is linked to the wider economic and social systems. Its performance in the political system influences the performance of these other systems, which via a process of feedback influences the fortunes of the party. The idea of a political party being a component in a complex and wider social system is not, of course, new. The systems approach to political analysis was fully, if rather abstractly, developed by Easton (1953, 1965) and Deutsch (1963). As it stands, systems theory is merely a conceptual framework for organizing ideas, and in the absence of detailed analysis and empirical evidence explains little of importance on its own. But, in the case of the crisis of the Labour Party, it provides a very useful device for organizing our discussion. Roughly speaking, Part I of this book is concerned with analysing the consequences of the policy failure for the Labour Party, and Part II is concerned with examining Labour’s contribution to this failure in the key areas of economic management and social security policy.

To set the scene, we shall briefly examine the nature of these three crises facing the Labour Party in this chapter before discussing them in more detail later. We shall also set out the main conclusions concerning Labour’s policy failures before discussing them in depth in Part II.

The ideological crisis

There have always been ideological divisions within the Labour Party, and periodic rows over ideological questions during its history. However, since the defeat in the General Election of 1979 the party has faced three major battles, all of which were at root ideological. These were the conflict over internal party democracy, particularly the question of mandatory reselection of MPs and a wider franchise for the election of party leader; the split with the Social Democrats, which led to the formation of the Social Democratic Party in March 1981; and the problem of entryism by the revolutionary Left, particularly the Militant Tendency.

We shall argue that each of these had its origins in the failures of policy performance of the Wilson and Callaghan governments, particularly the conflict over intra-party democracy. The starting point of the campaign by the Left to change the constitution was the defeat in the General Election of 1970. After the defeat the party swung to the Left and radical new policies were developed to avoid what was seen as the failure and drift of the Wilson government (Hatfield, 1978). The Left worked initially through the elaborate network of policy subcommittees set up by the National Executive Committee to develop policies especially for economic management and industrial intervention. These were incorporated into Labour’s Programme for Britain, 1973 (Labour Party, 1973), which was the most radical restatement of party policy since the war. In office these proposals, particularly the ideas on industrial policy, were quickly abandoned and after 1976 the party in government resumed the policies of economic management by deflation, characteristic of much of the postwar era.

The Left grew in strength in the 1970s, as the economic orthodoxy produced an ever-increasing slump, but after the defeat in the General Election of 1979 it changed strategies. It realized that controlling party conference, the forum for initiating new policy, was not enough. It had to obtain control over the parliamentary party and the leadership. This produced the campaigns over mandatory reselection, the control of the Manifesto, and the election of the leader. The campaign by the Left was spearheaded by the Labour Co-ordinating Committee, originally set up in 1978, and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy, set up in 1973 following the refusal by Harold Wilson to accept the conference decision to nationalize twenty-five leading industrial companies (Kogan and Kogan, 1982). The former was concerned with questions of policy, and the latter with questions of constitutional change.

The Campaign for Labour Party Democracy pursued three aims: the mandatory reselection of MPs by constituency parties during the lifetime of each parliament; the introduction of an electoral college for the appointment of the party leader, containing representatives from the unions, constituencies and the parliamentary party; and, thirdly, the vesting of the right to draw up the Manifesto in the National Executive Committee, and the removal of the veto on the contents of the Manifesto of the leadership. This campaign was given a crucial boost by the defeat in the 1979 General Election. Following this election, the Left was able to turn an argument, previously used by the Right, against their opponents. This was the argument that ‘extremist’ policies produce electoral defeat, and ‘moderate’ policies electoral success. As we show in Chapter 5, Labour fought the 1979 Election on a very anodyne Manifesto following Callaghan’s refusal to accept a number of radical proposals, such as the abolition of the House of Lords. The ‘moderate’ Manifesto produced the worst electoral performance since 1931, a uniquely crisis election. In fact, the contents of the Manifesto have little influence on the electorate, as we point out in Chapter 4, but the argument that ‘moderate’ policies were required for electoral success was widely accepted in the party before 1979. The other important aspect of the electoral argument was that in 1978–9 the Callaghan government had ignored TUC and party conference decisions in incomes policy and gone ahead with the 5 per cent pay norm, which led to the so called ‘winter of discontent’. The Left were quick to point out that, if the government had followed conference decisions, the winter of discontent would not have occurred and Labour would probably have won the General Election. These two arguments gave a big boost to the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy.

Ultimately the Left achieved two out of the three objectives. In 1979 the annual conference accepted mandatory reselection of MPs. It also obtained a crucial victory in getting the abolition of the three year rule, the device which prevented the raising of policy or constitutional issues again for another three years after they had been discussed at a conference. This enabled the question of the electoral college and the writing of the Manifesto to be raised again in 1980, following their rejection in 1979. At the 1980 conference the election of the leader was deferred to a special conference in January 1981, and after much wrangling the party decided at this conference that the electoral college should consist of 40 per cent trade union delegates, 30 per cent constituency party delegates and 30 per cent parliamentary party delegates. The control of the Manifesto by the NEC was not accepted, but instead joint control was vested in the NEC and the Shadow Cabinet. The Left had won two out of the three objectives.

Jim Callaghan resigned from the party leadership in October 1980, immediately following the annual conference, but before the special conference. This meant that the election for leader was conducted under the old system. Many people regarded the timing of this resignation as a manoeuvre designed to ensure the election of a leader from the Right of the party before the new system could be introduced. If this were true, the plan misfired, since Michael Foot was elected leader. But the new electoral college was soon tested when Tony Benn challenged Denis Healey for the deputy leadership. The campaign for the deputy leadership was long and drawn out, and was clearly damaging to the standing of the party in the country. The year 1981 was a particularly bad one for Labour since all three ideological disputes over conference democracy, entryism and the SDP were going on at a time when the party was arguing over the deputy leadership. In December 1980 the party received the support of 47.5 per cent of the electorate in the Gallup Poll (Webb and Wybrow, 1981, p. 168). By December 1981, after a year of internecine warfare, support was down to 23.5 per cent, a uniquely low level for the main opposition party (Gallup Polls, 1981, p. 2). Denis Healey ultimately won the deputy leadership by a hairsbreadth, which ended this particular source of division.

The creation of the SDP was a major influence on the political standing of the Labour Party. The split which led to the emergence of the new party had been building up ever since the swing to the Left in the Labour Party in the early 1970s (Bradley, 1981). The first organizational evidence of the split was the creation of the Social Democratic Alliance in 1975 immediately following the EEC Referendum. The SDA was made up of pro-Common Market zealots, but it never attracted the support of any major figures in the party and soon degenerated into McCarthyite smear tactics of opponents on the Left. The Limehouse Declaration which inaugurated the Council for Social Democracy, the immediate forerunner of the SDP, was made the day after the special conference of January 1981. The formal breach with the Labour Party came finally in March 1981, when the SDP was launched.

The immediate cause of the split was thus the victory of the Left over the electoral college system for electing the leader. But the underlying long-term cause was the increasing isolation of the revisionist and Gaitskellite wings of the party in Parliament. We review the main doctrines of revisionism in Chapter 5, but in the present context the major problem was that revisionism in practice failed to deliver the goods. It failed really on two grounds. Firstly, there was no distinctively Social Democratic economic policy other than orthodox Keynesianism. When this failed in the 1960s, partly because it was misapplied – as we shall see in Chapter 6 – the rest of the revisionist programme failed too. Crosland most clearly articulated revisionism in his classic book, The Future of Socialism (Crosland, 1956), in which he set out a vision of an increasingly egalitarian society made possible largely by redistribution from economic growth. When the economic growth was not achieved, neither was the greater equality. Shortly before his death, Crosland found himself, much against his will, supporting large cuts in public expenditure which had the effect of increasing inequality. Thus the second failure of revisionism was the failure by its advocates to stick to the ideals of equality when the going became tough. The acceptance of a kind of weak monetarism by a Labour Cabinet in 1976, a Cabinet which contained a majority of revisionists, represented the final death knell of the doctrine. This produced the increasing isolation of the Social Democrats in the Labour Party, which in turn produced the SDP.

The question of entryism was the third manifestation of the ideological crisis in the party, which again has its origins in the failures of the party in office. The Labour Party has always contained Marxists, and it has frequently suffered from entryism from the revolutionary Left. Before the Second World War, and in the 1950s, the threat came from the Communist Party, and increasingly over time from the Trotskyite Fourth Internationale, which periodically attempted to take over the Young Socialists. One of the apparently innocuous decisions taken in 1973 as a result of the swing to the Left in the party was the decision to abolish the list of proscribed organizations. Membership of such organizations rendered the individual ineligible for membership of the Labour Party. This gave the Militant Tendency an opportunity to take over the Youth Movement, as had a previous Trotskyite organization in the 1960s. But, unlike this earlier case, nothing was done to prevent it, and Militant began to make inroads into the adult party, particularly in inner city areas which often had decrepit local parties. Essentially the failure of the Social Democratic case and the ever-increasing economic crisis provided an ideal breeding ground for the simplistic, messianic vision of the Militants. Finally, in 1981 the newly elected party leader supported the idea of an investigation into the activities of Militant, which was duly carried out by Ron Hayward, the General Secretary, and David Hughes, the national agent. This report found that the Militant Tendency was in breach of Clause II of the party constitution, which proscribes all groups ‘having their own Programme, Principles and Policy’ (Labour Party, 1982a, p. 13). At the 1982 annual conference the party constitution was amended in order to set up a register of non-affiliated groups within the party. Groups which do not conform to the party constitution will be ineligible for membership of the register and will in theory be expelled from the party. The register was aimed primarily at Militant, but at the time of writing it is not clear how many Militant supporters will actually be expelled from the party. However, the introduction of the register represents a decisive defeat for entryists like Militant, and it seems likely that their influence in the party will be reduced in the future.

The ideological crisis is perhaps the most visible of the current crises in the party. The membership crisis is less obvious, and has been going on for so many years that it attracts little public attention. But it poses a real threat to the future viability of the party.

The membership crisis

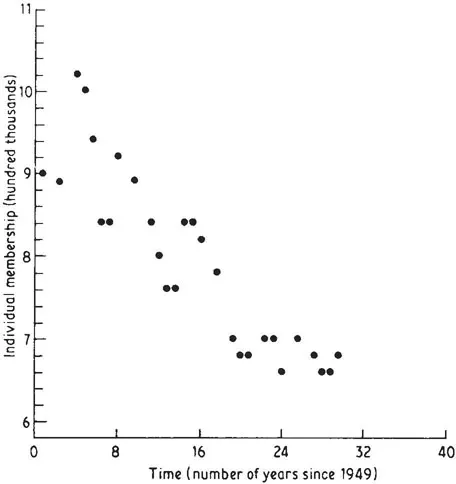

The decline in the published individual membership of the Labour Party over the years 1949 to 1979 can be seen in Figure 1.1. The correlation between individual party membership and the number of years since 1949 is a near perfect −0.91. Thus on published figures the party has been losing on average more than 11,000 members per year, and, since the published figures exaggerate the true membership, the actual loss of membership may well be higher than this. The published figures exaggerated the true membership, particularly up to 1979, because until 1980 the constituency parties were required to affiliate with at least 1000 members. When this rule was dropped individual membership fell from 666,091 in 1979 to 348,156 in 1980 (Labour Party, 1980, p. 84). However, constituency parties can still buy more individual membership cards from the central office than they actually issue so, as we argue in Chapter 3, these figures still exaggerate the true membership.

Figure 1.1 The decline in Labour Party individual membership, 1950–78 (Correlation between individual membership and time = −0.91)

Sources: Butler and Sloman (1980, p. 143) and Labour Party head-quarters.

We shall examine the reasons for this dramatic decline in the membership in Chapter 3, but for the moment we shall ask, why should this be a matter of real concern for the Labour Party? Are individual members actually important? In discussing individual members it is necessary to distinguish between the activists who keep the party going at the local level and the passive card-holding members. As we shall see in Chapter 3, the former are a minority of the total membership. As far as a passive membership is concerned, it is really only important to the party as a source of funds. Also it might be argued that passive party members will be more likely to vote Labour in an election than non-members, although this is debatable. Thus the real focus of attention in discussions of the importance of party members must centre on the activists.

The literature on political parties in Britain has tended to play down the importance of party activists, often arguing that their only important role is to support the party leadership. For example, in his classic study of British political parties McKenzie argued that the local parties were primarily servants of their respective parliamentary parties, whose function was ‘to sustain teams of parliamentary leaders, between whom the electorate is periodically invited to choose’ (1963, p. 66). More recently, McKenzie has argued that grassroots influence over policy in British political parties is incompatible with a democratic British system of government, since it removes power from Parliament and places it in the hands of an unelected outside group (McKenzie, 1982, p. 195). By contrast, Blondel (1963, p. 88) recognizes the important function of local parties in selecting elected representatives, but he has little to say about the role of activists in policy making.

We shall argue that party activists have three important roles to play in the Labour Party: in political recruitment, in policy making and in mobilizing the vote. For these reasons a rapid decline in the individual membership has disturbing implications for the future. To consider political recruitment first, the most important aspect o...