eBook - ePub

Financial Economics

Chris Jones

This is a test

Share book

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Financial Economics

Chris Jones

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Whilst many undergraduate finance textbooks are largely descriptive in nature, the economic analysis in most graduate texts is too advanced for latter year undergraduates. This book bridges the gap between these two extremes, offering a textbook that studies economic activity in financial markets, focusing on how consumers determine future consumpt

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Financial Economics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Financial Economics by Chris Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

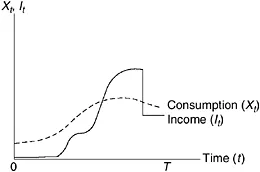

Individuals regularly make decisions to determine their consumption in future time periods, and most have income that varies over their lives. They initially consume from parental income before commencing work, whereupon their income normally increases until it peaks toward the end of their working life and then declines at retirement. An example of the income profile (It) for a consumer who lives until time T is shown by the solid line in Figure 1.1. When resources can be transferred between time periods the consumer can choose to smooth consumption expenditure (Xt) to make it look like the dashed line in the diagram.

Almost all consumption choices have intertemporal effects when individuals can transfer resources between time periods. Any good that provides (or funds) future consumption is referred to as a capital asset, and consumers trade these assets to determine the shape of the consumption profile. In Figure 1.1 the individual initially sells capital assets (borrows) to raise consumption above income, and later purchases capital assets (saves) to repay debt and save for retirement and the payment of bequests. These trades smooth consumption expenditure relative to income, where consumption profiles are determined by consumer preferences, resources endowments and investment opportunities.

There are physical and financial capital assets: physical assets such as houses and cars generate real consumption flows plus capital gains or losses, and financial assets have monetary payouts plus any capital gains or losses that can be converted into consumption goods. There are important links between them as many financial assets are used to fund investment in physical assets, where this gives them property right claims to their payouts. In frictionless competitive markets, asset values are a signal of the marginal benefits to sellers and marginal costs to buyers from trading future consumption. In effect, buyers and sellers are valuing the same payouts to capital assets when they make decisions to trade them, which is why so much effort is devoted to the derivation of capital asset pricing models in financial economics, particularly in the presence of uncertainty. Consumers will not pay a positive price for any asset unless it is expected to generate a net consumption flow for them in the future. In many cases these benefits might be reductions in consumption risk rather than increases in expected consumption. In fact, a large variety of financial securities trade in financial markets to facilitate trades in consumption risk.

While much of the material covered in this book examines trade in financial markets and the pricing of financial securities, there are important links between the real and financial variables in the economy. After all, financial markets function to facilitate the trades in real consumption, where financial securities reduce trading costs, particularly when consumption is transferred across time. Their prices provide important signals of the marginal valuations and costs of future consumption flows. To identify interactions between the real and financial variables in the economy, we examine the way capital asset prices change over time, and how they are affected by taxes, leverage, risk, new information and inflation. In particular, we look at how financial decisions affect real consumption opportunities.

Figure 1.1 Income and consumption profiles.

A useful starting point for the analysis is the classical finance model with frictionless and competitive markets where traders have common information. In this setting the financial policy irrelevance theorems of Modigliani and Miller (1958, 1961) hold, where financial securities are a veil over the real economy. That is not to say these securities are irrelevant to the real economy, but rather, the types of financial securities used and the way they make payouts, whether as consumption, cash or capital gains, are irrelevant. This is an important proposition because it reminds us that the values of financial securities are ultimately determined by the net consumption flows they provide – in other words, by their fundamentals. While this model appears at odds with reality, it provides an important benchmark for gradually extending the analysis to a more realistic setting with trading costs, taxes and asymmetric information to explain the interactions we observe between the real and financial variables in the economy. Considerable progress has been made in deriving asset pricing models in recent years by linking prices back to consumption, which is the ultimate source of value because it determines the utility of consumers. Most of this work is undertaken in classical finance models, where departures from it attempt to make the pricing models perform better empirically.

This book aims to bridge the material covered in most undergraduate finance courses with material covered in a first-year graduate finance course. Thus, it can be used as a textbook for third-year undergraduate and honours courses in finance and financial economics. Another aim is to provide policy analysts with an accessible reference for evaluating policy changes with risky benefits and costs that extend into future time periods. The most challenging material is presented at the end of Chapter 4, where four popular consumption-based pricing models are derived, and in Chapter 8 on project evaluation and the social discount rate. I benefited enormously from reading many of the works listed in the References section, but two books were particularly helpful. The book by John Cochrane (2001) provides nice insights into the economics of asset pricing, and is well supported by the book by Yvan Lengwiler (2004) that carefully establishes the properties of the consumption-based pricing model where the analysis in Cochrane starts.

In this book I have expanded the material on corporate finance and included material on project evaluation. Corporate finance is an ideal application in financial economics because a large portion of aggregate investment is undertaken by corporate firms. It provides us with an opportunity to examine the role of taxes and the effects of firm financial policies on their market valuations. Welfare analysis is used in the evaluation of public sector projects, and to identify the efficiency and equity effects of resource allocations by trades in private markets. In distorted markets policy analysts use different rules than private traders for evaluating capital investment decisions. These differences are examined and we extend a compensated welfare analysis to identify the welfare effects of changes in consumption risk. For that reason the book may also be useful as a reference for courses in cost–benefit analysis, public economics and the economics of taxation. We now summarize the material covered in each of the following chapters.

1.1 Chapter summaries

Intertemporal decisions under uncertainty

Uncertainty obviously impacts on intertemporal consumption choices, where consumers, when valuing capital assets, apply discount factors to their future net consumption flows as compensation for the opportunity cost of time and risk. Rather than include both time and risk from the outset, we follow Hirshleifer (1965) in Chapter 2 by using certainty analysis to identify the opportunity cost of time. This conveniently extends standard atemporal economic analysis to multiple time periods without the complication of also including uncertainty. It is included later in Chapter 3 using a two-period Arrow–Debreu state-preference model, which is a natural extension of the certainty analysis in Chapter 2. By proceeding in this manner we establish a solid foundation for the more advanced material covered in later chapters. Some graduate finance books treat uncertainty analysis, and in some cases, state-preference theory, as assumed knowledge.

The certainty analysis commences in an autarky economy where individuals effectively live on islands. We do this to identify actions consumers can take in isolation from each other to transfer consumption to future time periods through private investment in capital assets. For example, they can store commodities, plant trees and other crops as well as build houses to provide direct consumption benefits in the future. While this is a simplistic description of the choices available to most consumers, it establishes useful properties that will carry over to a more realistic setting. In particular, it identifies potential gains from trade, where the nature of these gains is identified by gradually introducing trading opportunities to the autarky economy. We initially extend the analysis by allowing consumers to exchange goods within each time period (atemporal trade) where transactions costs are introduced to provide a role for (fiat) money and financial securities.

It is quite easy to overlook some of the important roles of money and financial securities in a more general setting with risk, taxes, externalities and asymmetric information. In a certainty setting without taxes and other distortions consumers use them to reduce the costs of moving goods around the exchange economy. Money and financial securities will coexist as a medium of exchange if they provide different cost reductions for different transactions. Since money is highly divisible and universally accepted as a medium of exchange, it reduces trading costs on relatively low-valued transactions. In contrast, financial securities are used for larger-valued transactions and trades with more complex property right transfers which are less easily verified at the time the exchanges occur.1 If commodities are perfectly divisible, costless to transfer between locations, and traders have complete information about their quality and other important characteristics, the absence of trading costs will make money and financial securities redundant. Money is frequently not included in finance models due to the absence of trading costs on the grounds they are too small to play a significant role in the analysis. That also eliminates any transactions cost role for financial securities. When money is included in these circumstances it becomes a veil over the real economy so that nominal prices are determined by the supply of money.2 Once trading costs are included, however, money and financial securities can have real effects on equilibrium outcomes.

When consumers can trade atemporally in frictionless competitive markets they equate their marginal utility from allocating income to each good consumed. This allows us to simplify the analysis considerably by defining consumer preferences over income on the basis that consumption bundles are being chosen optimally in the background to maximize utility. This continues to be the case in the presence of uncertainty when there is a single consumption good. However, with multiple goods, risk-averse consumers care not only about changes in their (expected) money income in future time periods but also about changes in relative commodity prices as both determine the changes in their real income.3 This observation makes it easier to understand why in some pricing models the risk premiums are determined by changes in relative commodity prices.

The next extension to the autarky economy introduces full trade where consumers can trade within each period and across time (intertemporally) in a market economy. Initially we consider an exchange model where consumers swap goods in each time period and use forward commodity contracts to trade goods over time. The analysis is then extended to an asset economy by allowing consumers to trade financial securities. As noted by Arrow (1953), financial securities can significantly reduce the number of transactions. Instead of trading a separate forward contract for each good consumed in the future, consumers can trade money and financial securities with future payouts that can be converted into goods. Thus, money and financial securities can be used as a store of value to reduce the costs of trading intertemporally. But this introduces a wealth effect in the money market due to the non-payment of interest on currency. Whenever consumers hold currency as a store of value, they forgo interest payments on bonds; this acts as an implicit tax when the nominal interest rate exceeds the marginal social cost of supplying currency. Any anticipated expansion in the supply of fiat currency that raises the rate of price inflation and the nominal interest rate will increase the welfare loss from the non-payment of interest by further reducing the demand for currency. There are other important interactions between financial and real variables in the economy when we introduce risk and asymmetric information. By trading intertemporally in frictionless competitive markets, consumers equate their marginal rates of substitution between future and current consumption to the market rate of interest, and therefore use the same discount factors to value capital assets.

After extending the asset economy to allow investment by firms, we then examine the Fisher separation theorem. This gives price-taking firms the familiar objective of maximizing profit. Sometimes this objective is inappropriate. For example, shareholders are unlikely to be unanimous in supporting profit maximization when the investment choices of firms also affect the relative prices of the goods they consume. The Fisher separation theorem holds when these investment choices only have income effects on the budget constraints of shareholders. We then examine the effects of fully anticipated inflation in a classical finance model where the real economy is unaffected by changes in the rate of general price inflation. This establishes the Fisher effect where nominal interest rates change endogenously to keep the real interest rate constant, so that current asset prices are unaffected by changes in inflation. The real effects of inflation are obtained by relaxing assumptions in the classical finance model, including homogeneous expectations and flexible nominal prices.

Finally, the certainty analysis is completed by deriving asset prices for different types of securities such as perpetuities, annuities, share and bonds. In general terms, capital asset prices are determined by the size and timing of their net cash flows and the term structure of interest rates used to discount them. While this may seem a relatively straightforward exercise, it can become quite complicated in practice. There are many factors that can impact on the net cash flows and their discount factors, including, storage, investment opportunities, trading costs, inflation and taxes. After identifying the term structure of interest rates, we establish the fundamental equation of yield in a certainty setting. The term structure establishes the relationship between short- and long-term interest rates. This is important for pricing assets when their net cash flows are spread across a number of future time periods because the discount factors need to reflect the differences in their timing. Risk premiums are added to the short-term interest rates using an asset pricing model when the net cash flows are risky. These adjustments are derived later in Chapters 3 and 4. The equation of yield measures the economic return to capital invested in assets in each period of their lives. It identifies economic income as cash and consumption plus any capital gains or losses. Some asset prices rise over time, some fall and others stay constant. It depends on the size and timing of the cash flows they generate. Assets that delay paying net cash flows until later time periods must pay capital gains in subsequent years to compensate capital providers for the opportunity cost of time. In contrast, the prices of assets with larger immediate cash flows are much more likely to fall in some periods of their lives. In a frictionless competitive capital market every asset must pay the same economic rate of return as every other asset (in the same risk class). This is the no arbitrage condition which eliminates profit from security returns and makes them equal to the opportunity cost of time (and risk). It is an important relationship that appears time and again throughout the analysis in this book, and it provides extremely useful economic insights for predicting asset price changes and identifying the economic returns on assets.

The role of arbitrage can be demonstrated by computing the price of a financial asset with a net cash flow in the next period of X1 dollars when the nominal rate of interest over the period is i1. It has a present value of

where the discount factor 1/(1 + i1) converts future dollars into fewer current dollars to compensate the asset holder for the opportunity cost of delaying consumption expenditure. Whenever the current asset price (p0) falls below PV0 there is surplus with a net present value of

PV0 is the most the buyer would pay for this asset because it is the amount that would need to be invested in other assets (in the same risk class) to generate the same net cash flow, with PV0(1 + i1)=X1. In a frictionless competitive capital market arbitrage drives the market price of the asset (p0) to its present value (PV0). If the asset price results in p0(1 + i1) > X1 investors move into substitute assets which pay higher economic returns, while the reverse applies when p0(1 + i1) < X1. When the no arbitrage condition holds, the asset price is equated to the present value of its net cash flows, so that NPV0 = 0. In these circumstances the discount rate (i1) is the return every other asset (in the same risk class) pays over the same period of time.

Despite the simplicity of this example, it can be used to establish a number of very important properties that should apply to asset values. First, their net cash flows are payouts made to asset holders, and they are computed as gross revenue accruing to underlying real assets minus any non-capital costs of production. Second, the discount rate ...