eBook - ePub

Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose

Mick Short

This is a test

Share book

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose

Mick Short

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose examines how readers interact with literary works, how they understand and are moved by them. Mick Short considers how meanings and effects are generated in the three major literary genres, carying out stylistic analysis of poetry, drama and prose fiction in turn. He analyses a wide range of extracts from English literature, adopting an accessible approach to the analysis of literary texts which can be applied easily to other texts in English and in other languages.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Exploring the Language of Poems, Plays and Prose by Mick Short in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Who is stylistics?

1.1 Introduction

The short answer to the question 'Who is stylistics?' is that she is a friend of mine, and that I hope by the end of this book she might also become a friend of yours. You will find out who she is in the course of your reading; but another question you might like to ponder while you read this introductory chapter is why I have chosen that title for this chapter. I will tell you at the end of the chapter. The beginning of an answer to the question is that stylistics is an approach to the analysis of (literary) texts1 using linguistic description. Thus, in a book such as this, which is devoted exclusively to the analysis of literary texts, stylistics spans the borders of the two subjects, literature and linguistics. As a result, stylistics can sometimes look like either linguistics or literary criticism, depending upon where you are standing when you are looking at it. So, some of my literary critical colleagues sometimes accuse me of being an unfeeling linguist, saying that my analyses of poems, say, are too analytical, being too full of linguistic jargon and leaving insufficient room for personal preference on the part of the reader. My linguist colleagues, on the other hand, sometimes say that 1 am no linguist at all, but a critic in disguise, who cannot make his descriptions of language precise enough to count as real linguistics. They think that I leave too much to intuition and that I am not analytical enough. I think I've got the mix just right, of course!

If you already have some basic familiarity with linguistics you should have no difficulty with the various linguistic concepts I use in this book. However, in case you have no knowledge of linguistics, in the further reading at the end of this chapter I will suggest a couple of books for you to refer to if you come across a term or concept which is new to you and not explained in the text. I will also mention more specific linguistic readings, where relevant, in the suggestions for further reading at the ends of subsequent chapters. Where possible, I will explain new terms as I introduce them, but as an ex-English student who himself had to struggle with introductory linguistics books in the past, I know too well that what a particular writer assumes is well known is not necessarily 'old hat' for the reader.

When modern linguists began to take an interest in the analysis of literature, there was quite a lot of discussion as to whether linguists could really be of help to the literary critic. Because the debate was a border dispute over territory, it was often rather acrimonious. It probably reached its height of silliness when, in a published debate one linguist asked the critic he was debating with if he would allow his sister to marry a linguist.2 The critic replied that, knowing his sister, he would probably have little choice, but that he would much prefer not to have a linguist in the family.

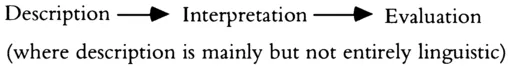

I regard myself as someone who is both a linguist and a critic, and so I would prefer to leave the general debate about whether criticism needs linguistic description to one side and get on with the practicalities of using linguistic analysis in order to describe and analyse literary texts. In case you want to follow up the debate, I provide references at the end of this chapter.3 The best way of seeing whether or not you find stylistic analysis helpful and enlightening will be to see it in action; but it will probably be useful if at first I make explicit some of my preconceptions. First of all, I regard literary criticism as having a 'core', its central, most important activity, and a less important 'periphery'. The core task for the critic is the job of interpreting (explicating) literary texts and judging them. Literary criticism can contain many other things; for example some specialists concern themselves almost entirely with the socio—cultural background against which particular works were written, and others look at the lives of authors and how their experiences led them to write in the way that they did. But these activities would not be of interest unless the culture to which the particular work belongs had decided that the writing concerned was valuable. Secondly, it seems to me that the essential core of criticism has three major parts:

Most people will agree that, at the end of the day, critics are interested in evaluating works of literature, that is, saying that work X is as good as, or better than, work Y, and so on. But it should be obvious that in order to decide that work X is good, or bad, we must first be able to interpret it. It makes no sense to say that a poem is good (or bad) but that you don't really understand it; still less to say that it is good (or bad) because you don't understand it. It follows, then, that interpretation must be logically prior to evaluation. This is what the arrow represents between those two words in the diagram above. I suspect that it is because understanding logically precedes evaluation that twentieth-century criticism has concerned itself for the most part with interpretations of poems, novels and plays while merely assuming literary merit (few, if any, critics discuss works which they consider to have little value). We know much less about the processes and criteria involved in the act of evaluation than many people would be prepared to admit.

The concepts of interpretation and evaluation referred to in the last paragraph, and the logical relations between them, are essentially post—processing concepts. By this I mean that the kind of interpretative and evaluative activities which critics publicly involve themselves in (when giving lectures, or writing books or articles) are activities which take place after reading the whole text. Indeed, a critic will probably have read the text involved carefully more than once. The student equivalent of this critical post—processing is the writing of essays or the reading out of seminar papers.

Note, however, that although interpretation is logically prior to evaluation in the post—processing critical situation we do not necessarily wait in our normal reading process until we get to the end of a text before making judgements. We almost certainly make them as we go along, depending on how we understand the text at that point, but we will alter our judgements as we alter our interpretation of (parts of) the text. Indeed, making hypotheses and guesses of this sort appears to be an essential part of the process of understanding as well as evaluation. But when we get to the end of our reading, our final, critical, judgement will be dependent upon our final understanding.

If interpretation is logically prior to evaluation it is also the case that what I have called description (which in turn involves analysis) is logically prior to understanding. Consider the following mundane sentence:

Example 1

Mary pushed John over

In order to know that this sentence means something like:

rather than:

we must already know that Mary is the subject of the sentence and that John is the object. Normally, we do not explicitly do a grammatical analysis of the sentence to arrive at this knowledge; rather, we just know implicitly or intuitively what the grammatical relations in the sentence are.

Now let us take a more literary example, a metaphor:

Example 2

Come, we burn daylight, ho!

(William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, I, iv, 43)

Besides the basic kind of linguistic information of the sort seen above, this time we also have to know that daylight cannot normally be the object of burn. The verb burn usually takes as its object a word or phrase which refers to something which can be burnt, but daylight does not fall into this category. It is only after deducing that what the line says cannot literally be true that we can go on to construct a non—literal interpretation for it (e.g. 'we are wasting time'). Stylistics is thus concerned with relating linguistic facts (linguistic description) to meaning (interpretation) in as explicit a way as possible. And what is true for sentences here is also true for texts. When we read, we must intuitively analyse linguistic structure at various levels (e.g. grammar, sounds, words, textual structure) in order (again intuitively) to understand the sentences of a text and the relations between them. We usually perform this complex set of tasks so fast that we do not even notice that we are doing it, let alone how we do it. Our understanding of the linguistic form and meaning is thus implicit. But when we discuss literature, as critics do, we need to discuss meaning in an explicit fashion. Stylisticians suggest that linguistic description and its relationship with interpretation should also be discussed as explicitly, as systematically, and in as detailed a way as possible. One advantage of this is that when we disagree over the meaning to ascribe to a text or part of a text, we can use stylistic analysis as a means to help to decide which of the various suggestions are most likely. There may, of course, be more than one valid interpretation, but, again, it is difficult to decide on such matters without detailed and explicit analysis. I want to suggest, then, that stylistic analysis, which attempts to relate linguistic description to interpretation, is part of the essential core of good criticism, as it constitutes a large part of what is involved, say, in supporting a particular view of a poem or arguing for one interpretation as against another. Of course it is not all that is involved. For example, in the understanding of a novel or a play we might well be involved in comparing one character with another or noticing a parallel between the main plot and the sub—plot. What we know about the characters must come from the text, the words which the author has written; but the ability which we possess to abstract notions like character and plot from the sentences of a text is linguistic only in a more indirect sense than our ability to make sense of grammatical or sound structure. Very little is known of how we infer plot and character from the sentences of a text, and it would be a very brave linguist indeed who would try to include such things in his or her description in the current state of knowledge. Note, then, that stylisticians do not by any means claim to have all the answers.

By now you may be wondering how the stylistic analysis of literature differs from traditional practical criticism. Literary critics do, after all, use textual evidence to support what they say. And indeed there is some considerable overlap between stylistic analysis and the more detailed forms of practical criticism. The difference is, in part, one of degree rather than kind. Practical critics use evidence from the text, and therefore sometimes the language of the text, to support what they say. But the evidence tends to be much more selective than that which a stylistician would want to bring to bear. In that sense, stylistics is the logical extension of practical criticism. In order to avoid as much as possible the dangers of partiality, stylisticians, as I have suggested above, try to make their descriptions and analyses as detailed, as systematic and as thorough as possible. This will sometimes involve stating what you might regard as obvious or going down to a level of analysis that literary critics would be unwilling to tackle.

There is also a difference of kind, however, which I would like to make clear as my third major preconception. For many critics, new interpretations and views on literary works are the major interest. If you write yet another book on Hamlet, for example, you are unlikely to get a good critical press if you do not come up with a new interpretation of the play or a new view on it. But stylistic analysis is just as interested, if not more so, in established interpretations as in new ones. This is because we are also profoundly interested in the rules and procedures which we, as readers, intuitively know and apply in order to understand what we read. Thus, stylisticians try to discover not just what a text means, but also how it comes to mean what it does. And in order to investigate the how it is usually best to start with established, agreed interpretations for a text. We are all different from one another: we have differe...