![]()

Part I

Problems

![]()

Chapter 1

Urbanization: Sewage and Storm-water

For as long as humans have lived together in settlements, they have had an impact on their environment. Trees are cut down to make room for houses, roads are built, and wells are dug or streams are diverted to provide drinking-water. By far the biggest impact, however, is caused by human waste disposal. The larger and more dense the settlement, the bigger and more concentrated the problem. With the development of flush toilets, things really got out of hand.

For thousands of years, the flush toilet didn’t exist. People used ‘conservancy’ systems, such as earth closets, pit privies and cesspools, which return human waste to the land. The earth closet was basically a wooden seat with a bucket underneath. A hopper behind the seat contained dry earth, charcoal or ashes that emptied into the bucket when you pulled a handle. When the bucket became full, you replaced it with an empty one. The full buckets were collected regularly and transported to farms, where the contents were used as fertilizer.

Other popular systems included pit privies and cesspools. A pit privy was essentially a hole in the ground with a seat on top (and walls around it for privacy). Waste fell into the hole, where soil organisms went to work, breaking down the solid organic material. The liquid percolated into the surrounding soil. When the hole became full, you dug a new one. Cesspools stored human waste, but unlike pit privies, they didn’t treat it. They were lined, watertight pits that had to be emptied frequently, and their contents transported elsewhere for disposal.

Conservancy systems were used for thousands of years. It was only in the last century that they were replaced by the now-familiar water carriage system.

The Water Carriage Revolution

Water carriage has three basic components: a water closet (WC) or flush toilet that flushes your waste, sewers that carry away what you’ve flushed, and some form of disposal and possibly treatment of the waste at the other end of the sewers. Clearly it necessitates a lot more infrastructure than the conservancy system, and this didn’t appear overnight. The water carriage revolution took place relatively slowly, piece by piece, beginning with the invention of the WC.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE WC

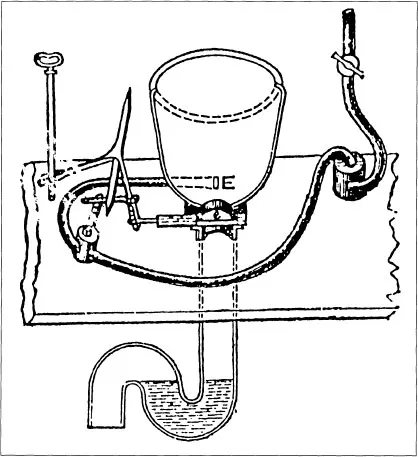

Although many societies have built latrines that emptied into watercourses, and even diverted watercourses to run underneath latrines, the first modern flushing toilet was not invented until 1596 by Sir John Harrington. However, his toilet had a number of weaknesses, including the lack of a water trap that prevented sewer odours from reaching the user’s nose, and (understandably) it did not catch on. Almost 200 years later, improved versions of the WC were designed independently by Cumming and Bramah. Their inventions included all the basic features of a modern flush toilet: flushing water, a holding tank, a flushing valve, an overhead supply and siphon and, perhaps most importantly, a water trap (see Figure 1.1). This time, the world proved more receptive.

Figure 1.1 Cumming’s Toilet

WCs offered several advantages over earth closets. They were cleaner and had fewer offensive odours. They flushed waste away, instead of leaving it to decompose. Finally, although WCs were expensive to install, water carriage was ultimately cheaper than paying someone with a horse and cart to collect and haul earth buckets. Beginning in the early nineteenth century, water carriage slowly gained ascendency over the conservancy system. There were two particularly compelling reasons for this shift: the increasing volume of urban waste, and the disease that accompanied it.

In the UK, the Industrial Revolution brought an influx of labourers from the country to the city to work in the newly created factories. Urban populations boomed, and demand for fertilizer in the country could no longer keep up with the increased urban supply of human waste. As more waste was produced in the cities, and as it had to be transported further and further to the farms, the conservancy system became uneconomic.

Box 1.1: Contemporary Account

There are hundreds, may I say thousands, of houses in this metropolis which have no drainage whatever, and the greater part of them have stinking, overflowing cesspools. And there are also hundreds of streets, courts and alleys that have no sewers; and how the drainage and filth are cleaned away and how the miserable inhabitants live in such places, it is hard to say.

John Phillips, engineer, London, 1847

At the same time, most towns weren’t prepared for the consequences of this population influx. Workers lived in shanty towns where there was no provision for removing domestic wastes. Excrement collected in courtyards, alleyways and streets, and diseases were spread by personal contact and by flies. Wells became contaminated by human wastes seeping from overloaded privies and cesspools, spreading even more disease. In these working class areas, diarrhoea, gastroenteritis, dysentery, typhoid fever, and paratyphoid fever were endemic.

WCs solved many of these problems. Waste was flushed away instead of being left to rot, significantly reducing the spread of disease. In Nottingham, for example, the Medical Officer of Health found that the rate of enteric fever was 50 per cent lower in areas of the town served by WCs than in areas served by earth closets, and 14 times lower than in areas served by pit privies.

SANITARY SEWERS

The real impetus for change came with the cholera epidemics that swept through the UK in 1831–32 and 1848–49, killing thousands of people. Sir Edwin Chadwick, the famous sanitary campaigner, blamed the unhygienic conditions in most manufacturing towns for the rapid spread of cholera. He strongly advocated a change from the conservancy system to a water carriage system for removing human waste. He also advocated the construction of sewers. At that time, many towns did not have sewers, and those sewers that did exist were intended for storm-water, not human waste. Most WCs discharged their wastes into cesspools and privy vaults which, because they were not designed to deal with the large volumes of liquid waste created by flush toilets, were in constant danger of overflowing. Chadwick fought against the restrictions that prohibited disposing of domestic waste into storm-water sewers, and suggested instead an ‘arterial system of drainage’ (Chadwick, quoted in Finer, 1952; pp 214–216) where sewers transported both storm-water and domestic sewage. His proposals were approved, and the water carriage revolution began in earnest.

Thus, in the UK, sanitary sewers were developed as a direct result of the cholera epidemics that swept the nation. This was also true in Paris, where sewers were constructed in response to the 1832 epidemic. However, a slightly different story unfolded in the US. Cholera never struck hard there, but two important factors paved the way towards sanitary sewers. As urban populations expanded, and as more and more people gained access to piped water, household water consumption increased rapidly. At the same time, the WC was gaining popularity, adding further to water consumption. The resulting waste-water overwhelmed cesspools and privies designed to handle more modest volumes, creating serious flooding problems and threatening to contaminate water supplies. Private citizens, engineers and public health officials all pressured municipalities to construct sanitary sewers.

Ironically, sewers created their own public health threats. In the nineteenth century, sewage treatment didn’t exist; sewers simply carried wastes to the most convenient place for disposal – often the nearest watercourse. At the time, engineers believed that ‘running water purified itself’ (Sedgwick, 1918; pp 213, 231–237), so dumping raw sewage into rivers and lakes was not a danger to downstream cities. Not surprisingly, this theory proved false. Although a river can assimilate a certain amount of organic waste, it can’t cope with huge volumes of sewage, and it can’t destroy every pathogen present in human waste. For example, 50 per cent of typhoid bacteria are destroyed in an aquatic environment in 1–3 days; 90 per cent are destroyed in 3–13 days; but the most resistant can live for...