![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction and Epistemologies of Educational Leadership and Organizations

My introduction to organizational theory occurred in my first doctoral course at Vanderbilt University with Professor Terry Deal and his four frames of organizations (Bolman & Deal, 2017). In my book on educational administration in a pluralistic society (Capper, 1993), I wrote about how the four frames were helpful in thinking about my leadership at that time in schools in the Appalachian region of southeast Kentucky. However, after reading William Foster’s work on critical theory and educational administration (Foster, 1986a), combined with my Appalachian experience, I wrote:

I knew that the literature and research (or “stories”) I had studied in educational administration, both theoretically and practically, failed to address the range of “Others” I had experienced as a teacher, administrator, and researcher. I then learned … that the stories I had been told [in graduate school] were limited to structural functionalism or to a few “interpretive” stories, the latter via my training in qualitative research methods. (Capper, 1993, p. 2)

Thus, in my 1993 book, I advocated a multiple paradigm approach to educational administration that extended beyond Bolman and Deal’s four frames grounded in structural functional and interpretive epistemologies to include critically oriented epistemologies such as critical theory and feminist poststructuralism (Capper, 1993).

Understanding a range of epistemologies can help leaders/scholars determine the epistemological underpinnings of various educational practices and, in so doing, identify the limits and possibilities of those practices toward equity. For example, relying on structural functional, interpretive, and critical epistemologies, I analyzed educational practices, including Total Quality Management (Capper & Jamison, 1993a) quite similar to the current school improvement “science” movement (Bryk, Gomez, Grunow, & LeMahieu, 2015), outcomes-based education (Capper, 1994b), and site-based management (Reitzug & Capper, 1996). I also analyzed the spirituality in education literature from a critical perspective (Capper, 2005) and from a combination of structural functional, interpretive, and critical epistemologies (Capper, Keyes, & Theoharis, 2000). In addition, we conducted a critical examination of community in spiritually centered leadership for social justice (Capper, Keyes, & Hafner, 2002). With my co-authors, we also identified the epistemological conflict that leaders can face in practice from structural functional, interpretive, and critical epistemologies (Keyes, Capper, Jamison, Martin, & Opsal, 1999).

In addition to structural functional, interpretive, and critical epistemologies, I incorporated poststructural and feminist poststructural epistemologies to analyze education practices, including outcomes-based education (Capper & Jamison, 1993b), the knowledge base in educational administration (Capper, 1995), how spirituality is defined in education and leadership (Hafner & Capper, 2005), and educational assessments and accountability (Capper, Hafner, & Keyes, 2001). I also critiqued practices that were non-traditional and critical, including a feminist, poststructural critique and analysis of non-traditional theory and research in educational administration (Capper, 1992) and a poststructural critique of the critical practice of community-based interagency collaboration (Capper, 1994a; Capper, Ropers Huilman, & Hanson, 1994).

When the postmodern epistemology began to be applied in educational leadership, many scholars from traditional perspectives lumped critical theory and poststructural epistemologies together. In response, I explained the differences between critically oriented and postmodern epistemologies and how these epistemologies could be applied to leadership practice (Capper, 1998). In that same publication, under the umbrella of critically oriented perspectives, I briefly described feminist theories, Critical Race Theory, and Queer Theory.

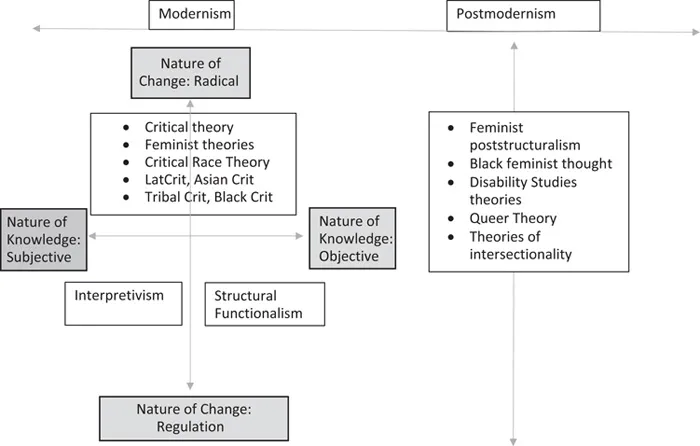

AN EPISTEMOLOGY FRAMEWORK

With this text, I extend this previous scholarship on epistemological analysis and implications for leadership practice by addressing Critical Race Theory, Black Crit, LatCrit Theory, Asian Crit, Tribal Crit, Queer Theory, Disability Studies theories, Black feminist epistemology, and theories of intersectionality, and how these epistemologies can inform organizational theory. To provide a guide to the epistemologies, I developed a figure to represent the epistemologies featured in this book and their relationship to each other (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 An Epistemology Framework

Arguably, drawing rigid boundaries around the epistemologies and arraying them in a heuristic requires many caveats. Using the words of Lather (1991), I recognize the limitations of such a framework:

[I]ts system of analytic “cells” reproduces the very binary logic poststructuralism attempts to unthink; its movement is … linearity at its most bare-faced; its division of [epistemologies] is reductionist and dualistic; its central categories are reifications that are represented as pure breaks with the past … I could go on and invite you to do so. But I have found the chart a useful pedagogical tool. (p. 159)

In agreement with Lather, students have found the framework helpful as one way to identify the historical trajectory and relationship among epistemologies that they may be learning about in disparate ways in their graduate programs.

Whereas in this book I describe the unique aspects of each epistemology, the epistemologies vary in how sharply they can be defined and compared to one another. Accordingly, the parameters of the epistemologies continue to evolve and, because of the complexities of educational, organizational, and social life and the contested history of the epistemologies, any description of the epistemologies and their applications to organizational theory and leadership should not be considered final. Further, I selected these epistemologies based on their salience to organizations, leadership, education, and equity, but others could argue for differing typologies (English, 1993; Sirotnik & Oakes, 1986).

The epistemological framework begins with Burrell and Morgan’s (2003) sociological theory framework aligned along two axes. The horizontal axis represents the nature of science or the nature of knowledge (i.e., epistemology, or how we come to know or entire systems of knowing) from objective at one end of the continuum to subjective at the other. The vertical axis represents the nature of change – at the bottom of the continuum the nature of change remains oriented to regulation; at the top end of the continuum the nature of change is considered to be radical toward social justice ends.

At this top end of the radical change continuum, Burrell and Morgan differentiated between the right quadrant of radical change associated with the objective nature of knowledge (radical structuralism) and the left quadrant of radical change associated with the subjective nature of knowledge (radical humanism). For our purposes, instead of parsing these differences, we will examine critically oriented epistemologies anchored in radical change that extend across the subjective/objective nature of knowledge.

To orient the reader to the differing epistemologies and to each associated chapter in the book, I next provide a quite brief overview of each epistemology, akin to riding a motorcycle through an art gallery. Each chapter that follows goes into detail about each epistemology.

Structural Functionalism

Beginning on the right lower quadrant, if the nature of knowledge is objective (horizontal axis) and the nature of change is oriented toward regulation (vertical axis), then the overarching epistemology and associated theories are structural functional (Chapter 3). The primary goal of structural functionalist epistemology focuses on efficiency. Bolman and Deal’s (2017) structural frame, bureaucracy, top-down leadership, positivism, and quantitative research methods not oriented toward equity reflect the structural functional epistemology.

Interpretivism

In the lower left quadrant, when the nature of knowledge is subjective (horizontal axis) and the nature of change is oriented to regulation (vertical axis), then this combination describes the interpretivist epistemology (Chapter 4) – the goal of which centers on understanding. Theories of human relations, Bolman and Deal’s (2017) human resources frame, and qualitative research methods that do not address equity all emanate from the interpretivist epistemology. Although interpretivist epistemologies with their focus on participation and human relations are often considered the antidote to structural functionalism, both epistemologies ignore privilege, power, identity, oppression, equity, and social justice. As described in Chapter 2, nearly all theories of organizations are grounded in structural functionalist or interpretivist epistemologies.

Critically Oriented Epistemologies

Moving to the top part of the change axis, the epistemologies located here are all focused on radical change toward justice and what I have termed “critically oriented epistemologies” (Capper, 1998, p. 354). Critical theory originated first among these epistemologies (Chapter 5). Foster (1986a, 1986b) initiated the application of critical theory to educational leadership. Theories of social justice, equity, and critical qualitative research methods originate out of critical theory.

Citing the limits of critical theory relative to gender and then race, feminist theories (Chapter 6) and Critical Race Theory (CRT) (Chapter 7) followed. Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995) applied CRT to education for the first time, and López (2003) considered CRT implications for educational leadership, the first scholar to do so. Most recently, Black Crit has emerged as one critique of CRT (Dumas & ross, 2016). All these epistemologies at the top end of the radical change continuum claim social justice as the ultimate goal (a term I will critique in Chapter 5 on critical theory). Importantly, all the debates between quantitative and qualitative research methods – the former anchored in structural functionalism, the latter in interpretivism – have ignored critical approaches to research methods that emanate from the radical change end of the continuum and critically oriented epistemologies.

In response to the limitations of CRT in legal studies, LatCrit and Asian Crit emerged, which were then applied to education along with Tribal Crit (Chapter 8). Building on the limitations of feminism and feminist poststructuralism, Black feminist epistemology emerged (Chapter 9).

The Modernism/Postmodernism Continuum

All the epistemologies discussed thus far – structural functionalism, interpretivism, critically oriented epistemologies, including critical theory, feminist theory, Critical Race Theory, LatCrit Theory, Tribal Crit, Asian Crit, and Black Crit Theory – are all grounded in modernist thought on the modernism/postmodernism continuum. Although all these epistemologies have fundamentally different origins and goals, they all share some commonalities. Modernism considers knowledge along a continuum from objective to socially constructed. Within modernism, power is conceived as all or nothing whether power is authoritarian (structural functionalism) or empowering (critically oriented) – a person either holds power or does not, a person either experiences oppression or does not. Educators in modernist approaches believe that individuals have an essential nature, which remains stable, fully aware, or in need of others to bring forth this awareness. Whether educators initiate change in a top-down fashion (structural functionalism) or as a result of considering multiple perspectives (interpretivism) or dialogue (critical theory), educators taking modernist approaches agree that change evolves in either incremental or radical ways, both linked to ideas of cause and effect.

Postmodern/poststructural epistemologies (though these terms differ, for our purposes consider them similar) were initially considered in educational leadership in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Anderson, 1990; English, 1998). Rather than working toward a goal in terms of change, a poststructural epistemology calls into question the end-point itself – whether the goal focuses on efficiency (structural functionalism), understanding (interpretivism), or social change (critically oriented epistemologies). With an interest in the complexities of decision-making and dissensus, a poststructural epistemology questions decision-making associated with dialogue and consensus that can oversimplify and mask power inequities and create an illusion of community. Rather than viewing power as all or nothing in modernist epistemologies, poststructural epistemologies view power as complex, plural, decentralized, and complex (see Chapter 6 which compares and contrasts feminist, poststructural, and feminist poststructural epistemologies).

Additional epistemologies emerged in response to the limitations of critically oriented epistemologies and postmodern epistemologies – all of which combine aspects of the two. Feminist theorists disagreed with many aspects of critical theory and postmodern philosophy; thus feminist poststructuralism emerged (Chapter 6). Given the timing of the emergence of poststructuralism, scholars of Disability Studies theories (Chapter 10) and Queer Theory (Chapter 11) have been strongly influenced by postmodern thought, and the tenets of these two epistemologies reflect that influence.

Theories of intersectionality arose with the work of legal scholar Crenshaw (19...