eBook - ePub

Attribution Theory

Applications to Achievement, Mental Health, and Interpersonal Conflict

Sandra Graham,Valerie S. Folkes

This is a test

Share book

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Attribution Theory

Applications to Achievement, Mental Health, and Interpersonal Conflict

Sandra Graham,Valerie S. Folkes

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This unusual volume begins with a historical overview of the growth of attribution theory, setting the stage for the three broad domains of application that are addressed in the remainder of the book. These include applications to: achievement strivings in the classroom and the sports domain; issues of mental health such as analyses of stress and coping and interpretations of psychotherapy; and personal and business conflict such as buyer- seller disagreement, marital discord, dissension in the workplace, and international strife. Because the chapters in Attribution Theory are more research-based than practice- oriented, this book will be of great interest and value to an audience of applied psychologists.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Attribution Theory an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Attribution Theory by Sandra Graham,Valerie S. Folkes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Searching for the Roots of Applied Attribution Theory |

University of California, Los Angeles

One of the unexpected consequences of the growth of attribution theory has been a corresponding increment in attributional applications to everyday problems and concerns. This introduction looks into the past to find an answer to the question: “Why has attribution theory been so amenable to practical use?” The products of my search also provide a historical context for the present book.

The theories that are highlighted in this chapter were proposed by Lewin, Heider, Rotter, and Weiner, with secondary discussion of Atkinson and Kelley. The editors have asked me to focus upon my work and how this was influenced by others. I do this with great modesty: My approach happens to provide the guiding theoretical system for this book, which includes a number of my former students as chapter contributors. However, it is known by this writer as well as by the readers that there are many attributional analyses, these are often incommensurate, and each has its own historical antecedents and confirmatory set of data.

I begin this chapter by documenting the overriding influence of Kurt Lewin on attribution theory and attribution theorists. Lewin is the starting point because of his known focus on theory utilization (action research) and because his role in attribution theory has been insufficiently acknowledged. In addition, he was an important influence on two theorists who greatly influenced my work.

KURT LEWIN: THE PRACTICAL THEORIST

In his biography of Lewin, Alfred Marrow (1969) pointed out the simultaneous thrust of theory and application that directed Lewin’s vast energies. Lewin’s dictum, “there is nothing so practical as a good theory,” is one of the few (the only?) aphorisms that has originated in experimental psychology. It is therefore not unreasonable to presume that students and coworkers of Lewin would be guided by his unified theory-application aims. Thus, to the extent that Lewin’s influence on attributional thinking can be documented, we should be alerted to look for both theoretical development and theory utilization among the proponents of attribution theory.

Lewin’s (1935, 1938) approach was so catholic that different aspects of his thinking were incorporated by different psychologists. In seeking the roots of attribution theory, Lewin’s ideas require classification into two categories. First, he championed Expectancy-value theory, and illustrated the power of that conception in his explication of level of aspiration. These features of his work strongly affected Julian Rotter (1954) and John Atkinson (1957, 1964). Both these theorists embraced Expectancy-value theory and used level of aspiration, that is, the choice among tasks differing in difficulty, as one of their main research paradigms. Secondly, Lewin (as well as other Gestaltists of the period) clarified some of the determinants of object and person perception and expanded the knowledge of psychologists by pointing out the dynamics of part–whole relationships and force fields. These components of Lewin’s thinking are reflected in Heider’s (1958) elucidation of balanced states and attributions (as well as Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance and some aspects of Kelley’s writings). Both balance and attribution in part concern cognitive dynamics arising from the formation of units or wholes. For example, a prediction of balance theory is that if a good act is performed by a bad person, then a state of imbalance exists. This initiates a force toward cognitive change or balance so that the act is perceived as less positive or the person is perceived as more positive. Similarly, attribution theorists have documented that there is a tendency to attribute a good act to a person perceived as good (such as the self). That is, given a positive outcome, the perceived attributional source is in part determined by motivational forces, as documented by phenomena such as the so-called “hedonic bias” (the tendency to attribute success rather than failure to oneself). Hence, both balance and attribution are in part derived from identical Gestalt principles related to cognitive dynamics.

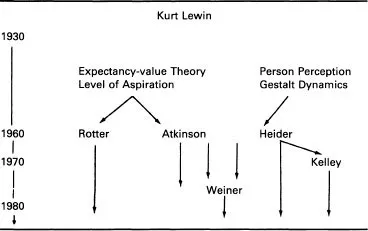

The contributions of Rotter, Atkinson, and Heider soon will be elaborated. For now, I merely wanted to note the immediate influence of Lewin on these three theorists (see Table 1.1).

In Table 1.1, Lewin and Heider are distinguished in terms of hierarchical levels, although they were contemporaries and Heider had an effect on others not necessarily familiar with the writings of Lewin. However, Lewin already had an impact on psychology in the 1930s and 1940s, whereas Heider did not dramatically influence psychological thinking until the 1960s. In addition, Table 1.1 is an oversimplification in that Heider also influenced Lewin, and all the theorists included in Table 1.1 as descendants of Lewin also were guided by major psychologists other than Lewin. What perhaps is most curious about the table is the relative independence of Rotter, Atkinson, and Heider. In spite of their partly shared origins and partly shared interests, they did not cite one another.

TABLE 1.1

Historical Influences in the Study of Attribution

Historical Influences in the Study of Attribution

Table 1.1 includes two other names “lower” in the time-frame hierarchy who are primarily associated with attribution theory: Harold Kelley and this writer. Kelley is a descendant of Heider inasmuch as the well-known “Kelley cube” is an in-depth examination of the covariation principle of causal inference, which was championed by Heider and philosophers before him. And I owe a great deal to Heider, particularly to his distinction between can and try as determinants of achievement performance. However, I also was guided by Expectancy-value theory as interpreted by Atkinson. These influences also will be examined in somewhat more detail later in the chapter.

I now want to turn to the attributional contributions of the psychologists in Table 1.1 who were directly or indirectly affected by Kurt Lewin. The discussion is organized into three sections. First, the contributions of Julian Rotter and the personality approach to causal ascriptions is presented. Next, and in much greater detail, the focus is on the social psychological approach to causal ascriptions, particularly as evidenced in the thinking of Fritz Heider and this writer. This section includes a reinterpretation of achievement theory as developed by Atkinson. Finally, I address why attribution theory has made such an impact on applied psychology.

The Personality Approach to Attributions: The Influence of Rotter

Rotter is identified with social learning and, as a clinician, wanted to develop a conceptual system that could be useful in dealing with clinical problems while remaining true to the logical positivism represented in social learning theory. Thus, he surely had both theoretical and applied concerns. As previously indicated, Rotter also accepted Expectancy-value theory, contending that the strength of motivation to perform an action is determined by the reinforcement value of a goal and the expectancy of attaining that goal. Clinical difficulties were anticipated when expectancy of success was nonveridical and when there was a low expectancy for a highly valued goal. Hence, one of Rotter’s central quests was to identify the determinants of expectancy of success.

In a series of experimental studies, Rotter and his colleagues (e.g., James & Rotter, 1958) documented that performance at skill tasks results in differential changes in expectancy of success when compared with performance at chance tasks. This laboratory experimental research led Rotter to speculate that some individuals might perceive the world as if it were composed of skill tasks, whereas others would perceive life outcomes as chance-determined. That is, there are individual differences in causal perceptions and these, in turn, result in disparate subjective likelihoods of success and failure across a variety of situations.

The locus of control, or I–E scale (I for internal, E for external) was constructed to measure individual differences in personal construction of the world as skill (internal) or chance (external) related (Rotter, 1966). However, to the best of my knowledge, the scale never has been successfully reported to relate to differences in expectancy of success or expectancy change. Rather, the I–E scale took on a life of its own, and it was indeed an active life. Locus of control was related to hundreds of different variables, few of any particular relevance to social learning theory or Expectancy-value theory. It also began to evoke comparions with a “good–bad” scale: It was “good” to be an “internal” inasmuch as this was thought to be related to information seeking, openness to experience, positive adaptation, and so on. Correspondingly, it was “bad” to be an “external.”

Even during the heyday of the I–E scale (say, from 1965 to 1980) questions were being raised about the breadth of personality traits, or their cross-situational generality. It was known, for example, that internal attributions for success were unrelated to the tendency to ascribe failure internally. In addition, it has long been recognized that the closer any set of scale items is to the situation in which a prediction is being made, the better the predictive validity of the scale. For example, if predicting motivation at high jumping, it is probably best to ask how motivated one is when high jumping, good to ask how motivated one is at sports, and conceivably of little value to determine how much one is motivated to achieve. Hence, specific scales began to be developed, such as the Health Locus of Control scale, which examines whether individuals perceive health-related outcomes as subject to personal or environmental control. In addition, individual difference scales began to be developed that incorporated properties of perceived causality in addition to locus, such as the stability of causes. These scales were particularly used to understand and predict depression (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978).

To summarize, the historical antecedents of the individual difference approach to attributions include Rotter’s attention to expectancy estimates, which was in part derived from his investigations involving skill and chance tasks, his acceptance of Lewin’s Expectancy-value theory, and research on level of aspiration. Over time, scales became more specific to particular situations and included properties of causality other than locus. In this book, this influence will be evident in the chapters by Amirkhan on stress, and Peterson on achievement strivings.

THE SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGICAL APPROACH TO ATTRIBUTIONS: THE INFLUENCE OF HEIDER AND WEINER

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance provided the dominant research paradigm for social psychology in the 1960s. Dissonance theory offered a noncommonsense approach to attitude formation and change based on the “fit” between cognitive elements. Thus, it also was a balance formulation. Inasmuch as attitudes have been the backbone of social psychology, and since there was a very conscious desire in the 1950s to progress beyond what was known as “bubba” (grandmother) psychology, the dominance of dissonance theory can be readily understood. But by the end of the 1960s dissonance theory had run its course. And this also is understandable. The many studies that were conducted left scholars searching for new places to leave their personal mark. In addition, dissonance was linked to drive theory, but this conception already had been discarded by most motivational psychologists. And of greatest importance, dissonance was conceptually sparse, so that there were few new directions toward which the theory could turn (hence resulting in increasingly novel experimental procedures to examine the same phenomena).

Attribution theory as first proposed by Heider and elaborated by Kelley replaced dissonance as the dominant paradigm within social psychology in the 1970s. This was in part because attribution theory fit within the overriding cognitive context of psychology that emerged in the early 1960s. Attribution theory was concerned with epistemology, or how people know. Heider, Kelley, and others presumed that individuals search for mastery and understanding, asking why events occurred and inferring the intents of others. Second, attribution theory is a psychology that does not rely on the nonobvious. People are accepted as attempting to be rational, guided in their inferences by informational inputs and directed in their actions by naïve psychological beliefs.

Heider, like Rotter, was concerned with causal perceptions in achievement-related contexts, but not from the perspective of an individual difference theorist. Rather, he began by analyzing the perceived determinents of achievement performance. He intuited that behavior is influenced by both “can” and “try;” can, in turn, was conceived as the relation between ability and the difficulty of the task. Both ability and effort hence were considered internal to the actor and components of skill, whereas objective task difficulty was an external determinant of behavior. Hence, Heider also emphasized the locus of causality in his theorizing.

The Weiner Approach

My contribution to attribution was in part to emphasize other dimensions or properties of causality in addition to locus. Starting from the ability–effort distinction made by Heider, it was reasoned that to the extent that these two causes of achievement performance differentially predict or determine some aspect of judgment or action, then an additional distinction between causes other than internal–external is needed.

One of my initial experiments linking attributional thinking to achievement strivings (Weiner & Kukla, 1970) documented that evaluation is particularly influenced by perceived effort expenditure: High effort is rewarded in achievement settings while low effort tends to be punished. This is not true for ability, which has little direct effect on evaluation when not confounded with outcome. Thus, given the differential consequences of ability and effort information on evaluation, a need to differentiate these causes was established.

My colleagues and I (Weiner et al., 1971) labeled the property distinguishing ability from effort as “causal stability.” Stability refers to the lability of a cause over time. Ability was considered to be rather fixed (akin to aptitude), whereas effort was conceived as variable, subject to fluctuation over short periods. Inasmuch as effort expenditure is perceived as variable, we speculated it would be linked with reward and punishment, which could then be used to influence expended effort. On the other hand, it appeared to us that rewarding or punishing ability had little instrumental function, since ability was conceived as fixed.

We had an additional insight at that time (Weiner et al., 1971). When Rotter contrasted skill (ability) with luck perceptions, he was actually comparing a respective internal, stable cause with an external, unstable cause. Hence, the disparate expectancy shifts that he documented could be attributed to either the locus or the stability dimension of causality. We later definitively documented that expectancy shifts are determined by causal stability rather than causal locus (see reviews in Weiner, 1985, 1986). For example, failure because of lack of ability produces lower expectancy of success than failure perceived as due to lack of effort, although both are internal determinants of behavior. Furthermore, failure because of low ability and failure due to an objectively difficult task may produce the same expectancy decrements, although ability is an internal determinant and task difficulty an external determinant of behavior.

But if causal stability is linked with expectancy of success (as it surely is), then what is the psychological significance of causal locus? To answer this question, we returned to Expectancy-value theory as construed by Lewin and later by Atkinson and Rotter (1957, 1964) and concluded that causal locus must be associated with the value of goal attainment. In this c...