eBook - ePub

Governing for Sustainable Urban Development

Yvonne Rydin

This is a test

Share book

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Governing for Sustainable Urban Development

Yvonne Rydin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Achieving urban sustainability is amongst the most pressing issues facing planners and governments. This book is the first to provide a cohesive analysis of sustainable urban development and to examine the processes by which change in how urban areas are built can be achieved. The author looks at how sustainable urban development can be delivered on the ground through a comprehensive analysis of the different modes of governing for new urban development.

Governing for Sustainable Urban Development:

- considers a range of policy tools that influence urban development and that constitute different modes of governing

- provides an innovative conceptual emphasis on learning within governing processes

- draws on a wide range of existing research, policy and literature together with case study material focussing on London

- is above all concerned with demonstrating how sustainable urban development can be delivered in practice.

This title be essential reading for students, academics and professionals in planning, urban design and architecture world-wide working to achieve sustainability.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Governing for Sustainable Urban Development an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Governing for Sustainable Urban Development by Yvonne Rydin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Urbanisme et développement urbain. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Sustainable Development and the Urban Agenda

Introduction

Sustainable development is now widely acknowledged to be an important policy goal, possibly the most important policy goal. This curious and not always well-understood mix of environmental protection, sustained economic activity and social welfare has become the public face of much policy activity. Its profile has been raised by the continuing and growing evidence of the scale and significance of climate change, by the enduring nature of profound social inequalities and even by the reversal of economic fortunes as economies slide into recession.

Sustainable development offers the prospect of a very different world and this includes our urban areas, our towns and cities and the built environments that they comprise. Urban areas are central to all aspects of sustainable development. They are centres of economic wealth-creation and yet, at the same time, locations of social deprivation. They can be associated with all sorts of environmental degradation – loss of green space, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions linked to energy use, waste generation and excessive water consumption to name but a few key aspects – and yet offer the scope for considerable resource efficiencies.

This raises the prospects of changing our urban areas to contribute more fully to sustainable development rather than undermine it. Change can, of course, occur within the existing physical fabric but there has been increasing interest in using the processes of urban development to drive change. Understood broadly, urban development can encompass new build, demolition and rebuild, refurbishment, regeneration and area improvement. These all have considerable potential for reshaping the built environments of urban areas.

This book looks at the role that urban development can play in delivering sustainable development. It considers how activity at the urban scale is related to the broader concept of sustainable development (the remainder of Chapter 1) and elaborates what sustainable urban development means at the scale of the building, the development site, and the urban area or region (Chapter 2). After an account of the market processes that drive urban development (Chapter 3), the main emphasis of the book is on how processes of governing can shape the delivery of sustainable urban development. Chapters 4 and 5 build a conceptual approach that highlights the importance of different modes of governing and different policy tools for achieving sustainability. In particular, it emphasizes the scope for learning within governing.

The next four chapters are structured around different tools for delivering sustainable urban development, unpacking the processes of governing and learning involved. Chapter 6 considers the role of information in a variety of forms, while Chapter 7 goes on to discuss financial incentives including subsidies, taxes and the influence of tradable permits such as carbon allowances. Chapter 8 looks at spatial planning and the management of the spatial distribution of urban development, with Chapter 9 covering regulation, focusing particularly on planning regulation. The book concludes with a summary of the main argument together with a consideration of the prospects for delivering sustainability through urban development (Chapter 10). It begins though by putting an interest in sustainable urban development in the context of broader debates about development and sustainable development in general.

What is Sustainable Development?

Much ink has been spilt trying to define the term ‘sustainable development’ and it has become commonplace to count the number of such definitions available and to point to the ambiguity surrounding the concept’s use. This ambiguity may well have contributed to the widespread use of the term in all sorts of contexts – policy statements, corporate reports, community initiatives – in the 1990s and 2000s. But it has also led to a certain dilution of the term so that it can be used to mean almost anything. The word ‘sustainable’ has been attached as a descriptor to many nouns and verbs: sustainable communities, sustainable consumption, sustainable business, sustainable oil and so on.

However, sustainable development had a quite clear and precise meaning in the document that is usually taken as the key reference point: Our Common Future or the Brundtland Report (WCED, 1987). The agenda for a United Nations’ commission, under the chairmanship of the former Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, was keenly debated before the commission started its work and was amended to cover the interrelationship between development and environmental concerns. As such it was seeking to address the extent of poverty on a global scale alongside the emerging global environmental agenda: pollution, resource exploitation, loss of biodiversity and global warming. Global warming in particular was achieving prominence as a new environmental threat at the planetary scale, although the well-established threat of nuclear war was also considered. Poverty, peace and the planetary environment were the three main themes of this keynote report.

Sustainable development was defined here as development that ‘meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED, 1987, p8). This sees the central problem as existing patterns of economic activity. These are deficient since they do not ensure that basic needs for today’s global population are being met. They also threaten future generations by effectively stealing the planet’s resources and environmental capacities from them to support current lifestyles. These two aspects are interconnected since the Brundtland Report makes the argument that poverty is also an important contributory cause of environmental degradation.

The solution lies in a ‘new era of economic growth’ (p8), which radically departs from prevailing patterns of economic activity to ensure that development provides for the world’s poor and respects environmental limits. So, in the Brundtland definition, sustainable development is very much about development, economic development but rethought to meet social and environmental goals. The radical nature of the Brundtland Report’s core message has, however, been softened and changed by the way that the term was used in the decade after the report’s publication. Box 1.1 provides some examples taken from national and international sustainable development strategy documents.

Box 1.1 Definitions of Sustainable Development

United Nations: ‘The achievement of sustainable development requires the integration of its economic, environmental and social components at all levels. This is facilitated by continuous dialogue and action (www.un.org/esa/dsd/index.shtml accessed 25.3.09).

European Union: ‘Sustainable Development stands for … a better quality of life for everyone, now and for generations to come. It offers a vision of progress that integrates immediate and longer-term objectives, local and global action, and regards social, economic and environmental issues as inseparable and interdependent components of human progress’ (www.ec.europa.eu/environment/eussd/ accessed 25.3.09).

United States of America: ‘our broad development goals of promoting economic growth, social development and environmental stewardship in such areas as forests, water, energy, climate, fisheries, and oceans management’ (www.state.gov/g/oes/sus/ accessed 25.3.09).

United Kingdom: ‘The past 20 years have seen a growing realization that the current model of development is unsustainable. In other words, we are living beyond our means. … Our way of life is placing an increasing burden on the planet’ (www.defra.gov.uk/sustainable/government/what/index.htm accessed 25.3.09).

India: ‘Progress has been monopolized by the chosen few at the unbelievably and indescribably large cost of the majority of mankind. The most disconcerting manifestation of this lop sided progress has been our planet’s ravaged ecology’ (www.envfor.nic.in/ accessed 25.3.09).

China: ‘China should make low carbon the strategy for the country’s social and economic development’ (www.chi-nasourcingnews.com/2009/03/10/411160-cas-releases-china-sustainable-development-strategy-report-for-2009/ accessed 25.3.09).

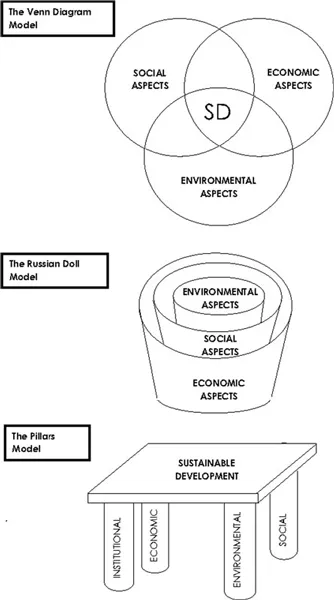

In response to this apparent looseness in how sustainable development is being understood, attempts have been made to provide a more rigorous definition. Three of these are represented graphically in Figure 1.1. The Venn Diagram is one of the most commonly used. It suggests that sustainable development has economic, social and environmental dimensions:

• The economic dimension is about using market-based dynamics to meet people’s needs, wants and desires and thereby provide the material basis for quality of life

• The social dimension is about the non-material dimensions of quality of life and equity, including a sense of community, local wellbeing and security, and the elimination of poverty, perhaps even the achievement of a more equal society

• The environmental dimension encompasses all those environmental goods, assets and services on which we depend and which are threatened by pollution, carbon emissions, resource exploitation and destruction of habitats.

Typically, in non-sustainable development, economic considerations dominate. Movements towards more sustainable development can be achieved by incorporating social or environmental concerns into decisions about economic development and, ideally, both would be integral to such economic decision making. Hence, truly sustainable development is indicated by the area of overlap at the centre of the Venn Diagram.

Figure 1.1 Three Models of Sustainable Development

The Russian Doll diagram again identifies economic, social and environmental dimensions as the key aspects of development but sees these as nested one inside each other. At the centre lie the environmental constraints that any development depends on; one layer out is the social dimension, indicating the importance of social structures for development activity. Economic considerations – understood as market processes and associated values – are only then considered, as the outside surface layer. As the Russian Doll metaphor suggests, economic considerations may be the most apparent facet of development but taking the doll apart makes clear the dependence of economic processes on society and the environment. By implication, sustainable development is economic activity that operates within the constraints of the environment (that is, does not cause irreversible environmental damage) and of society (that is, does not cause damage to the fabric of society through inequitable outcomes or exploitative processes).

The final diagram in Figure 1.1 illustrates the metaphor of four Pillars of Sustainability. Again the economic, social and environmental are all identified as pillars but they are joined by a fourth pillar – institutional. This fourth pillar harks back to another theme of the Brundtland Report: that government needs to work in a different way to deliver sustainable development. In particular, the report argued that a much more participatory approach was needed that engaged with and involved the communities affected by economic development with all its social and environmental consequences. All four pillars together are needed to hold up the slab of sustainable development suggesting an essential and equal emphasis on each dimension.

What all these diagrams have in common is the recognition that, while contemporary patterns of economic activity may have important negative impacts on society and the environment, nevertheless economic dynamics do play an important role in generating wealth within society, in providing for people’s needs and supporting investment for the future. Sustainable development is not an anti-economic concept. Rather it queries how economic activities currently interface with the social and environmental dimensions of our lives.

There are two aspects of these interrelationships that are particularly important. The first concerns how conflicts and tensions between the different aspects of sustainable development – between the economic, social and environmental – are handled, whether trade-offs are possible and, if so, how they can be effected. The second looks, more positively, at the prospects for synergies between these different aspects and the possibility of identifying win-win outcomes (that is, outcomes that deliver at least two of environmental, social and economic benefits) or even win-win-win outcomes.

The trade-off issue is particularly well handled by the differentiation between strong and weak variants of sustainable development (Neumayer, 2003). This approach derives from ecological economics and focuses on different types of capital. Economics typically distinguishes between the different forms of capital that contribute to production and hence the generation of profit and wealth. These forms usually extend to financial capital (money), physical capital (raw materials and machinery) and human capital (labour, skills and knowledge). However, concern with unsustainable patterns of economic activity has led to environmental capital being added to this list. Environmental capital covers the services and resources that environmental systems provide – resources, climate control, pollution sinks, food production, the gene pool of biodiverse ecosystems – and frames them as a form of capital that contributes to production processes. Some analysts would also add social capital as capturing the contribution of social interactions to economic activity but this is of less relevanc...