![]()

Chapter 1

Anger Disorders: Basic Science and Practice Issues

Howard Kassinove and Denis G. Sukhodolsky

Hofstra University, Hempstead, New York

Anger plays a significant role in everyday life. Sometimes it is short-lived, moderate in intensity, and, perhaps, even helpful. At other times it is persistent, severe, and highly disruptive. Overt anger can lead to negative evaluations by others, a negative self-concept, low self-esteem, interpersonal and family conflict, verbal and physical assault, property destruction, and occupational malad-justment (Deffenbacher, 1992). Suppressed anger is related to a number of medical conditions including essential hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cancer (Greer & Morris, 1975; Harburg, Gleiberman, Russell, & Cooper, 1991; Harburg, Blakelock, & Roeper, 1979; Kalis, Harris, Bennett, & Sokolow, 1961; Spielberger, Crane, Kearns, Pellegrin, & Rickman, 1991). These detrimental effects of anger have been known for a long time. More than 60 years ago, Meltzer (1933) reported that, “Anger has been called the worst propensity of human nature, the father and mother of craft, cruelty, and intrigue, and the chief enemy of public happiness and private peace” (p. 285). More recently, Dix (1991) concluded that even the common experience of parenting is constantly associated with anger. He noted that, “… average parents report high levels of anger with their children, the need to engage in techniques to control their anger, and fear that they will at some time lose control and harm their children” (p. 3).

Anger is also a frequent experience. According to Averill (1983), “Depending upon how records are kept, most people report becoming mildly to moderately angry anywhere from several times a day to several times a week (Anastasi, Cohen, & Spatz, 1948; Averill, 1979, 1982; Gates, 1926; Meltzer, 1933; Richardson, 1918)” (p. 1146). His reference list spans 75 years, suggesting stability of the anger experience as well as the everyday frequency. Given these observations, it is no surprise that anger is a common reason that leads people to seek professional help.

As with most phenomena of scientific and clinical interest, a number of different perspectives exist. Some scientists and practitioners believe that anger and aggression are but two views of the same event, with similar elicitors and consequences. Others believe they are different, and that anger precipitates aggression. Congruent with each of these positions, we note that both anger and aggression are frequent in the workplace, in the home, and even in schools. More than 1,000 people are murdered on the job annually, more than 2 million suffer physical attacks, and more than 6 million are threatened (Toufexis, 1994). Even schools are not safe. In the 5-year period from 1986 to 1990, in anger-correlated or anger-caused events, more than 300 people were killed or seriously wounded in American schools, and an additional 242 were held hostage at gunpoint (Goldstein, 1994).

Within and across individuals, angry feelings vary in frequency, intensity, and duration, and they are associated with a number of maladaptive conditions, as mentioned earlier. Clearly, it is important to understand the causes, correlates, and outcomes of anger, with the goal of developing effective remediation programs when anger is excessive and disruptive. In this chapter, we place the study of anger within the historical backdrop of the study of feelings. We differentiate annoyance, anger, fury, rage, hostility, and the behaviors of aggression and violence. This is followed by a review of theory, including some developmental and cultural issues. Finally, we review approaches to the study of anger, with a focus on social constructivism. Other approaches are elaborated on in subsequent chapters.

THE STUDY OF FEELINGS

People who are “in touch” with their feelings can develop a fuller appreciation for the variations and nuances of everyday interpersonal encounters. At moderate levels, positive and negative feelings can add zest and passion to people’s lives. However, when feelings are strong and negative, they can disrupt our behavioral, physiological, and thinking processes. When they are very strong and very negative, they can become highly disruptive and may even lead to (or become justifications for) crimes of passion committed while in an “insane” state. Because clients typically present with problems that involve negative feelings such as anger, anxiety, depression, and guilt, it is important for clinicians to have a full understanding of these common negative feeling states.

Regrettably, despite the obvious importance of feelings, psychologists and other social scientists have not given them consistent respect, either as causal variables for other human maladaptive behaviors and/or as phenomenological experiences worthy of study in their own right. Indeed, as Lewis and Haviland (1993) noted, “No one would deny the proposition that in order to understand human behavior, one must understand feelings … (and) the interest in emotions has been enduring: however, within the discipline of psychology at least, the study of feeling and emotions has been somewhat less than respectable” (p. ix). This seems strange to the clinical practitioner because feelings are the subject of many psychotherapy sessions.

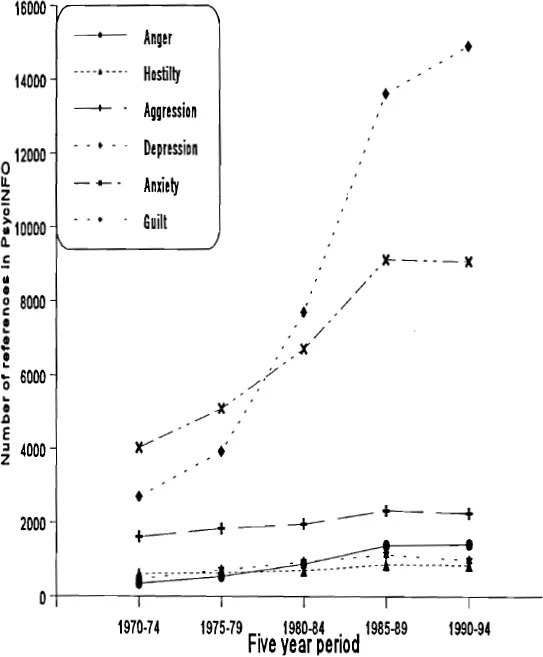

Of course, some clinical theories and intervention programs have focused on negative feelings. However, as shown in Figure 1.1, the primary interest during the past 25 years (based on keywords in PsycINFO) has been on anxiety and depression. Anger has been relatively ignored by scientists, thus little empirical help has been provided for practitioners.

Figure 1.1 Number of references to negative feeling words in the psychology literature (PsycINFO, 1970–1994).

The neglect of anger (and, it seems, guilt) as a phenomenon of interest is probably related to our attachment to the logico-empirical, positivist model. Scholars focused on the measurement of observables and minimized the scientific importance of phenomena available primarily through self-report. Within this tradition, it was relatively easy to study learning, worker productivity, aggression, and so on because the dependent variable could be reliably counted, weighed, or otherwise measured. Anxiety could be tackled if it were defined as “behavioral avoidance” or “physiological reactivity,” and depression was generally seen as a pattern of slow responding or low-frequency responding. In contrast, anger was seen as an epiphenomenon—one that is a part of the “mind” and, thus, not part of science. Figure 1.1 also shows that the number of studies referenced under aggression (a measurable and observable behavior) is uniformly higher than those referenced under anger. The keyword hostility was referenced the fewest number of times.

While scientists were avoiding talking to people about their phenomenological experiences, clinical practitioners were using self-reports (as well as in-the-office behavioral observations) to assess affective states. For practitioners, everyday language such as “I felt angry this week” has always been an acceptable and important part of clinical data. Their scientist colleagues’ unwillingness to use verbal reports to examine phenomena such as anger always seemed strange to clinicians. This is one likely reason that practitioners have rejected (or, at least, have not frequently read) the scientific literature as a source of practical guidance.

Well-trained clinicians do know, of course, that language (and, perhaps, thought) is an operant that is at least partially under environmental control. If, when clients are talking about their anger, practitioners say “uh-huh” or “I see” in a supportive tone, the probability is increased (at least for a while) that they will talk even more about their anger. If psychotherapists provide direct encouragement and reinforcement for getting anger “out” by screaming and beating a pillow, their clients will likely be even more angry in the future because they have actually practiced a social role known as the “anger script.” However, clinical experience shows that if clinicians simply ignore client verbalizations about anger, clients do not report that their anger disappears. Instead, the clients are likely to disappear from the office and report to others that their practitioners were “unsympathetic” and wouldn’t talk with them about their “real problem.”

Nevertheless, anger can be approached from a pure learning theory perspective. Indeed, although methodological behaviorists resist entering the “black box” of the mind, radical behaviorists (e.g., Salzinger, chap. 4, this volume) can explain much about internal phenomena such as anger and have contributions to make to clinical practice. For example, simply reinforcing the client for acting “as if’ he or she is calm and relaxed (not angry) is likely to lead to improvement. However, to consider anger as simply an operant verbalization may be to equate humans to parrots. With enough seeds (incentives and reinforcements), one can shape a parrot to say, “I feel angry” or “I feel better now!” However, few clinicians would find it acceptable to help a person solely by shaping a verbal response such as, “I feel OK. My anger is now gone.” Such an approach does not reflect the full spectrum of the human experience, especially the internal experience.

Most clinicians and scientists believe that humans are proactive and creative creatures, and that anger is a complex gestalt that is more than the simple product of reinforcements or punishments. Feelings such as anger are produced by active processes, including remembrances of the past, expectations of the future, awareness of current behavioral and physiological responses, comparisons of actual to desired behaviors, judgments of what others are thinking, and so on. Because these are reflected in the language clinicians and scientists use, and are shaped by their cultures (see Tanaka-Matsumi, chap. 5, this volume) and subcultures (see Tsytsarev & Grodnitzky, chap. 6, this volume), scientists and clinicians would both be wise to study and use verbal reports.

None of this is meant to deny the observation that people often say what is socially desirable. Verbal reports by psychotherapy clients may not be objectively true because of pressure to conform to social expectations. Also, sometimes, even if it is desired, clients may not be able to report accurately on what is happening internally (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). However, as Averill (1983) pointed out, social desirability is a confound only if it interferes with self-report. If social expectations, cultural norms, and accepted behavioral scripts are the focus of interest, as they often are when we study feelings such as anger, they are most likely to be reflected in self-reports. Thus, for example, when clients tell clinicians about their anger over discovering that their spouse is having an extramarital affair, the anger shows their social expectations and their desired marital state. A client’s language about feelings indicates how he or she appraises a situation, how he or she constructs the emotional experience, and how it is displayed. Averill’s (1983) argument is that “…we have tended to downgrade the great stock of knowledge that is embedded in ordinary language … (and) … psychologists should not impose a form of prior censorship on themselves by excluding from consideration a whole class of data and type of methodology, all in the name of science” (p. 1155).

As Averill (1983) noted, research findings can lead to situational and/or theoretical generalizations. Theoretical generalizations involve the significance of findings to explain underlying mechanisms. Thus, it might be shown reliably and consistently in the laboratory that subjects report feeling very angry when someone intentionally criticizes the shape of their nose while they are in a competitive situation with a member of the opposite sex. But how often does such an experience actually occur? Rather infrequently, and therefore this result has low situational generalizability. If clinicians wish to learn about the environmental or interpersonal situations that their clients are likely to be in, and the kinds of feelings they are likely to have in those situations, they would be wise to use self-report methods. There is much to be learned about the human anger experience from studying self-reports. We, however, are certainly not arguing against theories about anger based on lawful relationships and causal effects demonstrated in the laboratory. Instead, we believe the best way to understand angry feelings (and many other human phenomena) is to recognize that all kinds of data have assets and liabilities, and to use each class of data to its fullest.

FEELINGS AND EMOTION

According to Izard (1977), emotions take into account the conscious experience (i.e., the feeling), brain and nervous system processes, and observable expressive patterns (e.g., furrowed brow, clenched teeth, etc.), particularly on the face. In general, we use the term feelings to refer to the language-based, self-perceived, phenomenological state. In contrast, the term emotion refers to the complex of self-perceived feeling states, physiological reaction patterns, and associated behaviors.

Ortony and his social psychology colleagues (Clore, Ortony, & Foss, 1987; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988) agreed that emotions have different facets. However, they started with the assumption that, through language, people conceptualize potentially emotion-eliciting experiences in a particular way and, thus, they do or do not experience particular feelings. The authors’ perspective (i.e., that people’s language-based perceptions of the world—their broad construals and more narrow appraisal of specific events—cause them to experience certain feelings) is congruent with conceptions of the cognitive-behavioral therapies such as Ellis’ (1962, 1973) rational-emotive behavior therapy and Beck’s (1976) cognitive therapy. Indeed, Ortony, Clore, and Collins (1988) noted that there is an “abundance of psychological evidence that cognitions can influence and be influenced by emotions (e.g., Bower, 1981; Isen, Shalker, Clark, & Karp, 1978; Johnson & Tversky, 1983; Ortony, Turner, & Antos, 1983; Schwarz & Clore, 1983)” (p. 5). Further, they stated, “We think that emotions arise as a result of certain kinds of cognitions and we wish to explore what these cognitions might be” (p. 2). To do this, they distinguished which words refer to emotions and which to cognitions; their work has opened the door for exciting new research studies.

Using a social constructivist position, which begins with data (and definitions) from the common person, the authors asked university students to judge which words (from a pool of 585 possibilities) represent emotions (or what we call feelings) when the words were presented in the being state (e.g., I am abandoned; I am angry) versus the feeling state (e.g., I feel abandoned; I feel angry). Their hypothesis was that words judged to represent emotions would be so judged in both states, and would fit into a cluster of words that refers to internal, mental, and affective conditions. From this analysis, the following list of words of interest to us (i.e., anger-oriented words) represented emotions: aggravated, aggrieved, anger, angry, annoyed, bitchy, frustrated, fury, furious, hostile, hostility, incensed, irate, irked, irritated, mad, malice, malicious, outraged, peeved, pissed-off, rage, spiteful, vengeful, and violent. In contrast, the following words did not refer to emotions: abused, aggressive, antagonistic, awful, arrogant, cruelty, cynical, horrible, obstinate, rotten, sarcastic, stubborn, terrible, unpleasant, and willful. Aggressive was (as expected) judged to be an external condition, and thus is not an emotion according to the conception that emotions are internal events. Awful, terrible, horrible, and the milder unpleasant were judged to be in the external, not the emotion, category. These points are important because the cognitive therapies are typically based on the hypothesis that we can shift levels of disruptive emotionality (e.g., reduce intense anger to milder annoyance) by reevaluating whether the events are cognitively appraised as “absolutely awful” or “simply unpleasant.”

DEFINITION OF ANGER

We define anger as a negative, phenomenological (or internal) feeling state associated with specific cognitive and perceptual distortions and deficiencies (e.g., misappraisals, errors, and attributions of blame, injustice, preventability, andlor intentionality), subjective labeling, physiological changes, and action tendencies to engage in socially constructed and reinforced organized behavioral scripts.

Anger varies in frequency. Some people report feeling angry almost all of the time, whereas others rarely feel angry. Anger varies in intensity, from mild (typically labeled as agitation or annoyance) to strong (typically labeled as fury or rage). Anger also varies in duration, from transient to long term (i.e., holding a grudge). However, people express their anger experiences differently, thus many different behaviors (e.g., sulking, yelling, glaring, avoiding eye contact, leaving, making snide comments, etc.) are associated with the internal experience. It is the totality of specific cognitive and phenomenological experiences that differentiates anger from other feelings such as anxiety, sadness, and so on.

Our definition focuses on the phenomenology of the experience, but also recognizes that the behavioral display of anger plays a central role. It is congruent with Averill’s (1983) position that an “anger display” is a socially defined transitory behavioral role that is based on behavior patterns developed and reinforced in a person’s culture (see Tanaka-Matsumi, chap. 5, this volume). Anger is a reaction of the whole person, wherein the “correct” way to think and act is determined by modeling and reinforcement as the person develops. We do not deny the sometimes important role played by biophysical factors such brain tumors, insulin reactions, and so on, and therapists would be wise to be alert to the possibility of such problems with their angry clients. However, we believe that, as psychologists and psychotherapists, it is wiser to focus on patterns learned from other family members, television, school, religious teachings, and so on. To better understand anger, we first discuss aggression as it provides a contrast to the focus of this book—anger. Although there is an obvious and important relationship between anger and aggression, anger is an independent (or at least semi-independent) and neglected phenomenon worthy of study in its own right.

AGGRESSION (WITH COMMENTS ABOUT ANGER)

According to Berkowitz (1993), aggression has to do with motor behavior that has a deliberate intent—to harm, hurt, or injure another person or object. Aggression is thus goal directed. However, some forceful goal-directed behaviors are not instances of aggression even if some harm occurs because there is no intent to harm. Forcefully pushing a child out of the way of an oncoming car may lead to pain and bruising or bleeding of the child. However, the intent was to help, and thus the behavior is not aggressive. We agree with this position; for example, helpful anxiety-evoking behavioral psychotherapy techniques (such as flooding) are not instances of aggression because their intent is to help the client.

In contrast, Bandura (1973) stayed close to the behavioral perspective, which tries to avoid internal concepts such as intention. Thus, he considere...