The Guide to the Circular Economy

Capturing Value and Managing Material Risk

Dustin Benton,Jonny Hazell,Julie Hill

- 94 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Guide to the Circular Economy

Capturing Value and Managing Material Risk

Dustin Benton,Jonny Hazell,Julie Hill

About This Book

The term "Circular Economy" is becoming familiar to an increasing number of businesses. It expresses an aspiration to get more value from resources and waste less, especially as resources come under a variety of pressures – price-driven, political and environmental.Delivering the circular economy can bring direct costs savings to businesses, reduce risk and offer reputational advantages, and can therefore be a market differentiator – but working out what counts as "circular" activity for an individual business, as against the entire economy or individual products, is not straightforward.This guide to the circular economy gives examples of what this new business model looks like in practice, and showcases businesses opportunities around circular activity. It also: explores the debate around circular economy metrics and indicators and helps you assess your current level of circularity, set priorities and measure success; equips readers to make the links between their own company's initiatives and those of others, making those activities count by influencing actors across the supply chain; outlines the conditions that have enabled other companies to change the system in which they operate. Finally, this expert short work sets the circular economy in a political and business context, so you understand where it has come from and where it is going.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Step 1

Getting Hold of the Key Concepts

No. 1: Our economies are underpinned by natural resources

| Resources | The basics that underpin all of our life and economies – land, raw materials, energy, water. Land and water tend to be the hardest to substitute. |

| Biotic resources | Sources of materials and energy that come from plants or animals, whether farmed or wild – food, wood, paper, textiles such as cotton, wool and leather. Also generally thought of as 'renewable' – i.e. they grow and can replace themselves or are replaced through farming and forestry. Although these resources are renewable, many are under as much pressure from increasing consumption as non-renewable resources. |

| Abiotic resources | The mined resources– metals and minerals. Oil and coal are interesting as they were once biological materials (animals and plants) but as they are now fossil resources and not renewable, they tend to get classified with the mined resources. This means that plastics from oil (they can also be made from plants) come into this camp. |

| Primary and secondary resources | Primary are the resources coming straight from agriculture, forestry and mining. Secondary resources have been reclaimed from their first use. |

| Natural capital | All the stuff the planet provides that we take – from fish to forests to grazing land to minerals. A term used to make the point that without these basic resources, we wouldn't be able to generate monetary capital. |

| Ecosystem services | The 'life support systems' of the planet provided by natural areas – e.g. water and nutrient cycling, a stable climate, green space, natural beauty and recreation. These 'services' are also considered to be a part of 'natural capital'. |

| 'Stuff' | Rather unspecific, but generally conjures up materials and products rather than energy and water, and is a friendly term used to make people think about their personal consumption of materials. |

| Resource criticality | The idea that some specific resources are critical to a particular economy's success and may be subject to supply restrictions. These are often 'niche' (specialised and/or small quantity) but high-value materials that are central to particular technologies – for instance, the indium in touch screens or 'rare earth' metals in magnets. |

| Bioeconomy | A new term expressing the aspiration to shift the source of economic value from non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Biofuels and biomass sources of energy are one strand of this debate, but more economic value may be gained from applications in materials and chemicals. |

No. 2: Resources are becoming less ‘secue’ for a variety of reasons

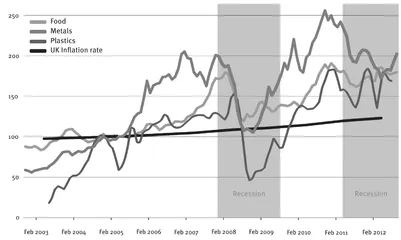

- A reversal in the trend of the last four decades of declining resource prices. The prices of food, metals and plastics of have risen in the last eight years faster than background inflation, and continued rising through a recession.

- Not only are prices rising, they are more volatile, with bigger spikes and troughs. This uncertainty is a big problem for businesses, stifling investment and inhibiting confident forward planning.

- Underlying these price trends are environmental pressures – although the basic metals, for instance, will not ‘run out’ any time soon, the increasing energy and water needed to access more dilute sources drives up costs.

- One of the factors underlying food price rises and limiting a shift to using more bio-based or ‘renewable’ materials is the competition for high quality agricultural land (for food, fuels and materials).

- On top of this, there are fears of restrictions on access to key resources by political decisions – for instance, the Chinese Government restricting export of ‘rare earth’ minerals to keep them for their own use.

- As demand for resources rises, and prices become more volatile and strained, we may see more resource nationalism – an effort to stop flows of key resources outside a country under stress.

- At the same time, the world is facing increasing demand for resources as global population rises, and the affluence of that population increases.

- climate change may mean a less predictable climate, disrupting access to raw materials and water. In response there are moves in several countries to regulate or price carbon emissions, which would have further impacts on energy and resource prices.

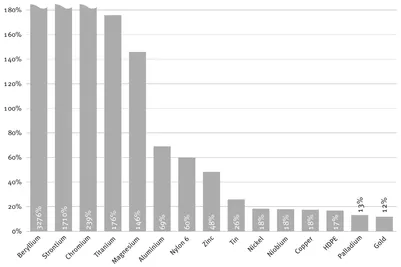

- These aren’t just abstract risks – putting a proper price on carbon (i.e. around €75 per tonne) would cause the price of primary aluminium to rise by 70 percent, chromium to rise by 240 percent and nylon to rise by 40 percent.

SOURCE: Green Alliance

- Companies are subject to increasing scrutiny of their supply chains by consumers and by campaigning groups, and their reputations are at risk in the event that environmental or social problems associated with their raw materials are uncovered. Recent high profile campaigns on conflict minerals, palm oil and coal-fired electricity in computer data-centres are prime examples. Social media means that there is nowhere to hide.

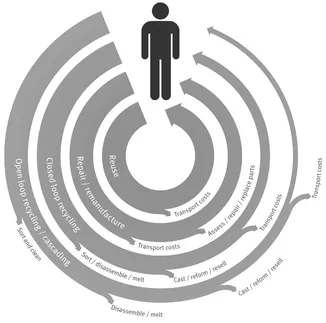

No. 3: Circular economy thinking gives companies more options in the face of resource insecurity

SOURCE: Green Alliance

- Leasing products to consumers is being examined as a new business model by many companies, extending it away from the current high value examples, such as cars and large industrial equipment, towards more everyday items such as appliances and clothes. Leasing creates an incentive for companies to recover the products and materials and get repeated value from them, while offering consumers the service they want, and assuring them of minimal waste. There are examples below under Step 2.

- Re-use is perhaps the most obvious but most neglected strategy, one which can involve complexity to establish, but then substantial financial savings. For instance, Sainsbury’s has a comprehensive re-use centre for equipment from its stores, established with the help of its facilities management company. This is now a highly successful and cost-effective operation (see Box on page 30 for more detail).

- Remanufacturing, which involves restoring a product to a like-new or better status, is a good strategy for companies where they are producing complex, higher value products. Siemens, GE and Philips all remanufacture medical imaging equipment such as scanners, and digger company Caterpillar (www.caterpillar.com/en/company/brands/cat-reman.html) has a much-quoted and highly profitable remanufacturing model. Remanufacturing is one of the least visible of the ‘circular strategies’, as its products are indistinguishable from new.

- Helping companies to establish ‘closed loops’ opens up new business opportunities. An increasing trend for joint venture arrangements has boosted business for plastics recyclers, for instance. Closed Loop Recycling (www.closedlooprecycling.co.uk/blog/ms-and-the-circular-economy.php), a company established to recycle PET bottles back into PET bottles, is based on a partnership between companies with demand for a recycled product (for instance, M&S), and a provider with the sorting technology to supply PET (Veolia). Similarly, the rapidly growing UK recycler ECO plastics (www.ecoplasticsltd.com/default.aspx) quadrupled its capacity between 2009 and 2014. With the help of Viridor and other joint ventures, it is supplying Coca Cola (www. coca-cola.co.uk/environment/coca-cola-eco-plastics-recyclingjoint-venture.html).

- internal recycling is often overlooked and can yield significant energy and financial benefits. In Japan, flat panel display manufacturers collect indium (www.japanfs.org/en/news/archives/news_id026099.html) tin oxide wasted in the production process and send it for recycling in a closed loop process that ensures that the reprocessor sends it back to the original manufacturers.

- Even obvious recycling strategies such as recovering steel can be improved with thoughtful use of information. Shipping line Maersk (www.worldslargestship.com/facts/cradle-to-cradle/) publishes a ‘product passport’ for its new ships showing where different grades of metals are used – the separation of these alloys that this makes possible has raised the value of their recycling by 10 percent.

- Replacing key raw materials with recovered alternatives can mean greater certainty of price or supply, as well as have reputational benefits. This will be increasingly true for plastics, where a combination of exposure to the price of oil, increased global consumption an...