eBook - ePub

Atlas of Slavery

James Walvin

This is a test

Share book

- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Atlas of Slavery

James Walvin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Slavery transformed Africa, Europe and the Americas and hugely-enhanced the well-being of the West but the subject of slavery can be hard to understand because of its huge geographic and chronological span. This book uses a unique atlas format to present the story of slavery, explaining its historical importance and making this complex story and its geographical setting easy to understand.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Atlas of Slavery an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Atlas of Slavery by James Walvin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Amérique du Nord. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Slavery in a global setting

The modern interest in Atlantic slavery and the African slave trade has, to a marked degree, overshadowed the study of slave systems in other parts of the world. When people speak of ‘slavery’ today they are likely to think of black slavery, and the slave system of the Americas. Yet American slavery is relatively recent, and in many respects unusual.

Wherever we look, slave systems dot (and sometime dominate) the historical geography of very different regions of the globe. From Indonesia to India, from South Pacific islands to Arabia, slavery was an unquestioned institution. So too was the supply of slaves (slave trades) to those regions, often from distant communities. Put simply, slavery and slaves were ubiquitous. Not surprisingly, then, wherever Europeans travelled in that age of maritime exploration beginning in the fifteenth century, they encountered slave systems. Perhaps the most important was the world of Islam.

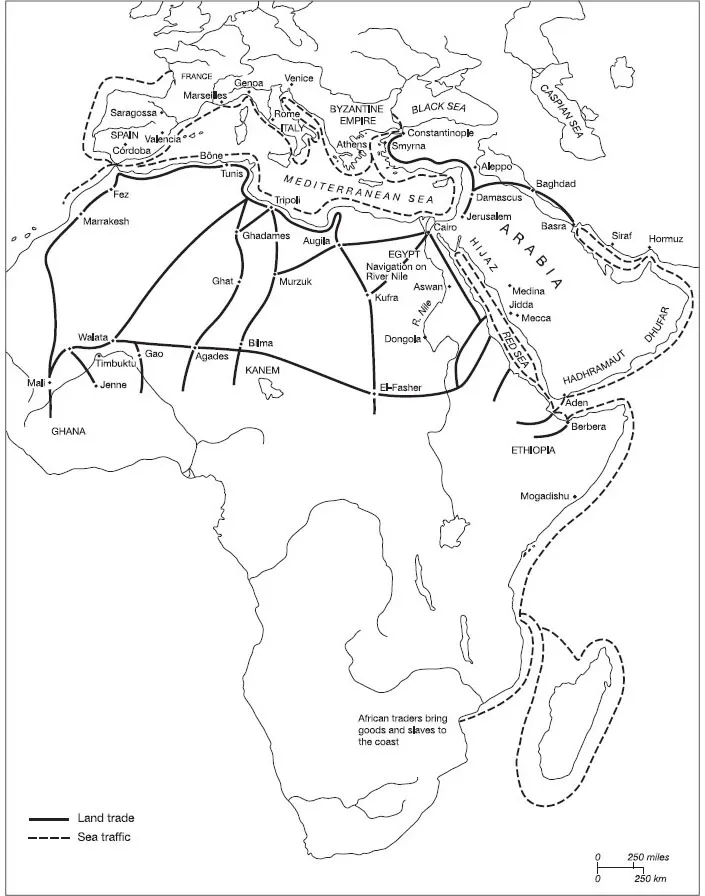

Europeans had long been familiar with the slaves of the Islamic world: from its earliest days Islam was associated with slavery. Muhammad owned slaves, the Qur’an makes frequent mention of slaves, and there was a flourishing debate about slavery among Islamic scholars. As Islam spread, slavery travelled in its wake, and slave routes evolved to supply the demand for slaves in a host of Islamic slave societies. Sub-Saharan Africa proved a rich and long-lasting source of slaves for the world of Islam. From the eighth to the twentieth century large numbers of slaves were moved, mainly by foot, across the Sahara to Islamic slave markets dotted around the Mediterranean. Most of those slaves were black Africans from sub-Saharan Africa, destined to be sold and settled in the Arab Mediterranean. Many inevitably perished en route, while others were settled as slaves within the Sahara. Some even found their way to mainland Europe, appearing for example in a number of late medieval and early modern paintings. Though many African slaves were men, wanted as soldiers or for heavy manual labour in mines or agriculture, the majority were women to be used as servants or concubines. The numbers involved are difficult to calculate, but they seem to have increased markedly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, prompted by economic growth in the Mediterranean and by aggressive slave trading in Africa itself.

Most of those slaves were captured violently in raids and then sold on to merchants or the overland caravans. It was, in addition, amazingly long-lived, surviving some twelve centuries. The most eminent scholar of the subject calculates that perhaps three and half million to four million slaves were transported across the Sahara in that period. It was, in Ralph Austen’s words, ‘one of the major examples of enslavement in world history’. It was variants of this existing internal African slave trade – overland routes, crossing the Sahara – that Europeans first encountered, from the fifteenth century onwards, and that they later tapped into for their initial slave supplies for the Atlantic islands and, later, for the Americas (Map 7).

Map 7 Caravan and seaborne trade, c. AD 1000

Source: After Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P. The New Atlas of African History, R. G. Collings, p. 47.

In the course of their maritime expansion in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Europeans encountered slave systems around the world. The Dutch for example established trading posts in Southeast Asia, where slaves formed a majority of the local urban population (in Malaya, Sumatra and Java). Not surprisingly, the Dutch adapted themselves to local slave systems and, when necessary, imported slaves to serve their own interests. The Dutch also imported slaves from other islands in Southeast Asia and from as far afield as India, Ceylon, Bengal and even Africa. This Dutch demand for slaves in Asia created a widespread and violent slave-trading system and spawned slave-trading states, from Borneo to the Philippines. In their turn, those slave traders’ activities ranged as far as the Bay of Bengal. This trade in slaves took on a life of its own, and when Europeans turned against global slavery in the nineteenth century (keen to abolish what they had once sponsored) they found the task daunting and were not able effectively to curb and outlaw slave trading in the region until the late nineteenth century.

Dutch colonial settlements in South Africa were initially founded as way stations for their lucrative trade in Asia. There, and in the Mascarene Islands (Mauritius and Réunion), the Dutch imported slaves mainly from Madagascar and East Africa. Slaves were also moved south to the Cape from other parts of Africa, from Indonesia and from India. India itself had long been home to numbers of slave systems, a fact that the British colonial government simply accepted until the rise of the British abolitionist movement began to target Indian slavery. But before the formal British abolition of slavery in India (in 1843), Indian slaves had been transported to South Africa, the Mascarene Islands, Ceylon and Indonesia (Map 8).

Map 8 Global slave-trading routes

Source: After Freeman-Grenville, G. S. P. The New Atlas of African History, R. G. Collings, p. 83.

Time and again, then, slavery around the world was sustained by large-scale movements of people; by the enslavement of distant peoples; and by their transportation, by land, water and oceanic crossing, to far-flung slave markets and slave societies. Sometimes the numbers involved were huge. Moreover, most of this was in place before the development of the Atlantic slave trade, and much of it survived long after slavery in the Americas had been abolished.

The slave systems that developed in the Americas were distinctive, however, not least because they came to be defined by race. Europeans had known about black Africa for centuries before their early maritime contacts with West Africa. Overland trade routes, the overlap of trading and colonial empires in the Mediterranean, the dissemination of myths and rumours (about the peoples and goods of black Africa): all and more had lapped back and forth between Europe and Africa. Trade routes across the Sahara, along the Nile and thence throughout the Mediterranean had brought African and European peoples face to face, although admittedly in very small numbers. Yet there was nothing necessarily enslaved about those encounters. Europeans did not assume that the peoples of black Africa were destined to be slaves to white owners or masters. Within a very short space of time, however, Europeans came to view the African as a natural slave, a person to be enslaved and purchased and to be transported in huge numbers over vast distances across the ocean, to work for European settlers on the far side of the Atlantic. Something quite dramatic had changed.

Europeans had effectively dispensed with slavery at home before they developed their slave colonies. In the case of England, slavery had died out long ago (though more recently, and less completely, in Scotland). Bondage had been basic to medieval society, and even after the decline of medieval serfdom (itself different from slavery) large numbers of English people were effectively tied to their masters, notably apprentices, pauper children and, until 1772/75, Scottish miners.

But none of these groups were slaves, comparable with the Africans shipped into the Americas. Moreover, the forms of slavery that Europeans created in the Americas proved to be among the most hostile and repressive in recorded history. The paradox remains that Europe saw the gradual securing of individual rights to ever more people in Europe at the very time that Europeans expanded and intensified slavery across vast tracts of the Americas.

Europeans took small numbers of slaves to the Americas from the early days of exploration. They also enslaved indigenous peoples. The pioneers of that expansion into the Americas were the Spanish and the Portuguese, but from 1580 onwards, the most influential Atlantic migrations fell into the hands of northern Europeans, notably the Dutch and then the English. In the process, and as large parts of the Americas fell under European control, more and more Africans were shipped across the Atlantic. Moreover, substantial proportions of the Europeans who travelled across the Atlantic were also unfree – indentured labourers tied to their masters – but not slaves. Africans began to account for the greater share of all people migrating across the Atlantic, and as slavery developed, the British were critical. Before 1800 nine out of ten people carried into the Americas on British ships were unfree, mainly slaves but also indentured labourers. How did this vast movement of humanity come about? How and why did Europeans turn to Africa for labour and manpower in the Americas?

Chapter 2

The ancient world

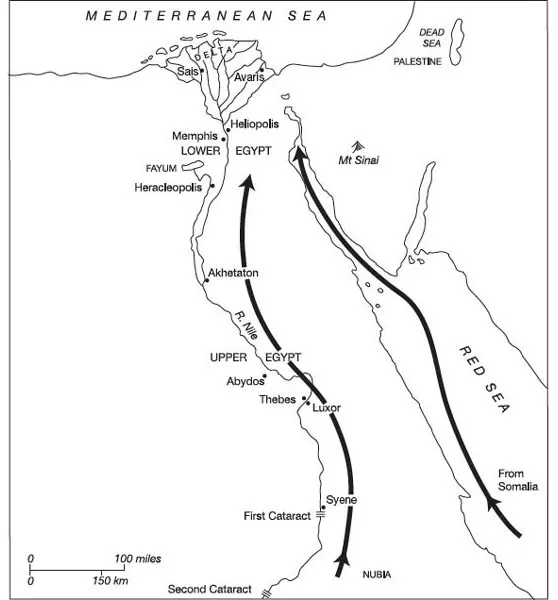

Slavery was commonplace in a host of ancient and traditional societies. For example, it played a major, integral role in societies from ancient Egypt to the wider world of classical antiquity. Indeed, many of the surviving artifacts and buildings of those societies, now awash with millions of tourists, from the Pyramids to the urban fabric of ancient Greece, were built by slaves. In all those societies, slaves were recruited from outside: by warfare, by raids and kidnapping and by trade and barter in humanity. There were slave markets for the transfer and supply of fresh slaves arriving from the edges of trade and military conquest. Throughout the history of ancient Egypt, large numbers of slaves were acquired by military means (though the slave population also grew of its own accord). The New Kingdom (1560–1070 BC) expanded throughout the present-day Middle East and Sudan; many thousands of Nubians from the Sudan were dragooned as slaves, working in agriculture, in manufacturing and in the military. Females inevitably found their way into domestic slavery. Other African slaves came to Egypt from the coast of Somalia (Map 9).

Map 9 Slave routes into ancient Egypt

Source: From A World History, Third Edition by William H. McNeill, copyright © 1967, 1971, 1979 by William H. McNeill. Used by permission of Oxford University Press, Inc. and the author.

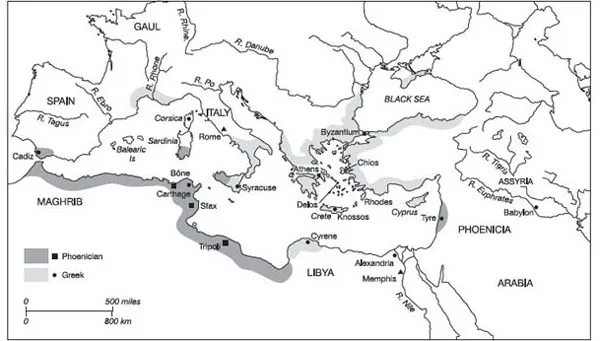

Greek civilization was equally bound up with slavery, and trade thrived in enslaved peoples, especially in the classical period (450–330 BC). Slaves could be found in large numbers in all the major city-states, where they were bought and sold as objects, with men used in heavy work, women normally in domestic chores. Again, slaves were recruited by violent expeditions. Curiously, the rise of slavery paralleled the rise of Greek democracy, for the slaves gave citizens the freedom to take part in their civic duties. Although slavery changed over time, it became a defining characteristic of Greek civilization. Slaves from the East passed through the Greek slave markets of Chios, Delos and Rhodes (Map 10).

Map 10 The Phoenician and Greek world

Source: After Curtin, P. D. et al. (1995) African History, Longman, p. 37.

Slavery in the Roman Empire is better known (because more recent and therefore better documented). The successes of the Roman legions throughout that far-flung empire provided legions of slaves for the Roman heartlands, from the northern boundaries of the empire in Britain to the southern limits in Africa. It has been calculated that the golden age of Rome was maintained by the importation of upwards of half a million slaves in one year. Indeed, Roman armies returned in triumph to the imperial capital ahead of their retinue of conquered slaves from as far afield as Germany, Britain and Gaul. Slaves were ubiquitous: as domestics, as labourers in Roman agriculture, in the hell of the mines and, of course, for entertainment in the Colosseum. Few areas of Roman life remained untouched by slaves. Rome may...