eBook - ePub

Fundamental Principles of Law and Economics

Alan Devlin

This is a test

Share book

- 424 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fundamental Principles of Law and Economics

Alan Devlin

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This textbook places the relationship between law and economics in its international context, explaining the fundamentals of this increasingly important area of teaching and research in an accessible and straightforward manner. In presenting the subject, Alan Devlin draws on the neoclassical tradition of economic analysis of law while also showcasing cutting- edge developments, such as the rise of behavioural economic theories of law.

Key features of this innovative book include:

- case law, directives, regulations, and statistics from EU, UK, and US jurisdictions are presented clearly and contextualised for law students, showing how law and economics theory can be understood in practice;

- succinct end- of-chapter summaries highlight the essential points in each chapter to focus student learning;

- further reading is provided at the end of each chapter to guide independent research.

Making use of tables and diagrams throughout to facilitate understanding, this text provides a comprehensive overview of law-and-economics that is ideal for those new to the subject and for use as a course text for law-and-economics modules.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Fundamental Principles of Law and Economics an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Fundamental Principles of Law and Economics by Alan Devlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part 1

Economic Theory, Law, and Morality

1 Background Principles in Microeconomics

2 Essential Concepts in the Law and Economics Literature

3 Utilitarianism, Neoclassical Welfare Economics, and the Ethics of Markets

Chapter 1

Background Principles in Microeconomics

Chapter Contents

A. Utility and the Distribution of Scarce Resources

B. Consumer Choice and the Law of Demand

C. Firm Behaviour and the Law of Supply

D. Market Equilibrium, and an Illustrative Application to Criminal Law

E. Game Theory

Key Points

References and Further Reading

Understanding the economic contribution to law requires some familiarity with the “dismal science”. This chapter introduces the basic elements of microeconomic theory, including the laws of supply and demand, price theory, and the concept of equilibrium. These basic pillars of economics yield insights into broad swathes of law.

A. Utility and the Distribution of Scarce Resources

We begin with the most basic question – what is economics? Broadly defined, it is the study of how society allocates scarce resources. Whenever people value a good (or service) but there is an insufficient quantity available to satisfy everyone, a dilemma arises: who should get the desired items? This may be a question of moral desert, but can we articulate a coherent rule of decision? A promising answer might be to rank consumers based on inter-personal comparisons of the happiness that each person would experience in obtaining the good. The concept of “utility” captures the magnitude of an individual’s satisfaction. Allocating scarce, but valuable, goods to consumers who would benefit the most from them makes sense. To distribute scarce resources justly, society could rank consumers according to their respective utilities, and allot the products accordingly.

Nevertheless, such an approach would face formidable obstacles. Inter-personal comparisons of utility are notoriously difficult to conduct. Extreme differences in circumstance may make optimal allocation of a scare product clear – for example, a life-saving drug would presumably confer more utility on a person who is suffering from the relevant medical condition than on one who merely fears contracting it. Nevertheless, in most cases, distinctions between consumers’ utilities would be unclear and thus incommensurate. To complicate matters further, a declarant’s assertion that he values the good more than others is not credible. Every consumer would have reason to say so, regardless of whether it is true.

Furthermore, the availability of a desirable resource is not fixed. Society can often produce more goods, thus satisfying more demand. Maximising utility would require expanding production until the cost of building an additional unit equals the utility that that extra unit would yield. Yet, how can the government know the right quantity to produce, and how can it spur private actors to produce it?

Market economies solve this dilemma through property rights. Since people have unique information concerning their tastes, they can trade with one another to their mutual benefit. The market process relies on prices, as proxies for value, to coordinate economic activity. We have said that ranking consumers by utility would enable society to distribute scarce products, but such an approach is unworkable because governments cannot make inter-person utility comparisons. The economic solution is to equate willingness and ability to pay with preference, which may itself be a rough proxy for one’s utility. In other words, one can infer utility from a person’s voluntary market choices, which demonstrate “revealed preferences”. From this view, if two people wish to consume a good, but only one is available, the person who offers a higher price should receive it.

In addition to facilitating the efficient distribution of resources – “efficient” meaning that the person willing to pay the most for a scarce resource obtains it – a price-based market incentivises manufacturers to expand production, thus further enhancing welfare. Additional benefits ensue. Producers’ profits attract competition, which forces output even higher and causes price to fall toward manufacturers’ marginal cost of production and distribution. This leads to economically desirable conditions of allocative and productive efficiency.1

A key principle of economics is that the amount of wealth in a society is not set. Resources are more valuable in some people’s hands than in others, and so the law can do more than distribute income: it can help to create wealth where none existed before. As but one example, in 2010, the US Chamber of Commerce tied 75% of post-World War II growth in the US economy to innovation.2 The economy did not find that value; it created it.

Some people can use a resource more productively than others. Similarly, some derive different satisfaction than others in consuming a good. In either situation, if a person who does not value the relevant good the most currently owns it, assigning that resource to a higher-value user will increase social welfare. This gives rise to a crucial insight: agreements into which informed, competent, parties consensually enter advance welfare by satisfying the preferences of the contracting parties as long as the relevant arrangement carries no harmful third-party effects. Thus, in recognising property rights and enforcing contracts, the law facilitates voluntary exchanges that enhance value.

Armed with a basic understanding of preferences and the role of price in rationing scarce resources accordingly, we can proceed further. First, we need to say more about how markets operate, both in terms of how consumers make preference-satisfying decisions and how supply and demand interact to determine the price of a good and its associated output.

For the uninitiated reader, this discussion may appear alien to the nature and operation of law. After all, we do not typically think of law, and much of the behaviour that it seeks to regulate, in terms of markets. Yet, economists can fruitfully study almost all aspects of the legal system using price theory. For instance, one can understand tort law as spurring both an efficient level of risk-bearing behaviour and optimal precautions. It does so by imposing a price (a “Pigouvian tax”) through the tort system that equals the negative externality that the potentially negligent behaviour creates.3

B. Consumer Choice and the Law of Demand

Consumer behaviour is complex. People are idiosyncratic, buffeted by motivations and pressures that differ from one individual to the next. Out of this morass of influences, neoclassical economists focus on core incentives, devising formal models of decision making that predict consumer choice. Rationality is the organising principle. By assuming that consumers rationally maximise their utility, economic models can generate hypotheses about future behaviour. The relevance of this methodology to law becomes clear when one realises that “consumers” within the realm of legal analysis include people engaging in risky conduct (tortfeasors), promisors considering whether to breach their contracts, litigants, innovators, and – yes – even criminals.

The assumptions underlying such neoclassical models are simplified and unrealistic when applied to individual consumers, who often behave irrationally. Nevertheless, these assumptions are critical, as without them it would be impossible to devise a model of choice sufficiently workable to enable researchers to study key determinants of behaviour. By devising simplified models of decision making, social scientists sacrifice descriptive realism for predictability and feasibility.

1. Rationality as an organising principle

The core neoclassical hypothesis is that individuals are rational maximisers who choose the optimal combination, or “bundle,” of goods and services that satisfy their preferences. The only constraints on people’s consumption decisions are budgetary limitations and the cost of acquiring and processing information with which to inform their decision making.

For the time being, accept that each consumer has a preference ordering regarding the various goods (or services) that are available for her consumption. A “utility function” encapsulates which products are attractive to a particular person and to what degree. Assume that consumers’ preferences are complete and internally consistent (“transitive”), and thus give rise to an ordinal ranking.4 Furthermore, if a product is attractive to an individual then, other things being equal, she would rather have more of the good than less of it (this is the quality of “strong monotonicity”).

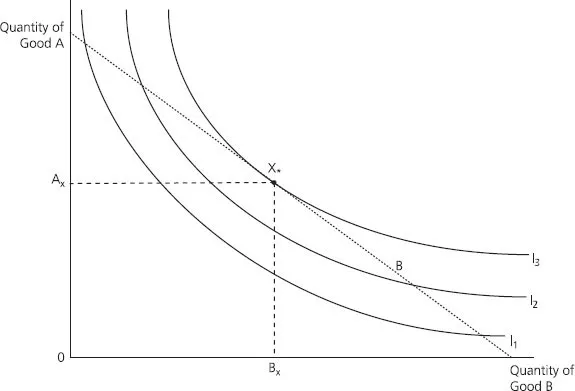

In weighing the available mix of products that he might purchase, a consumer will be indifferent between particular combinations of goods. In other words, he will not prefer one such bundle over another. One can display this phenomenon graphically using an “indifference curve”. If one such curve is above another then, by the assumption of preferring more desirable goods over less, a rational person would rather consume any chosen combination of products on the higher curve than on the lower one. In this world of choice, our consumer’s problem is one of constrained optimisation. To make a rational consumption decision, he would choose the bundle of goods that provides the maximum possible utility given the limited amount of money that he has available.

In the diagram below, a consumer must choose how much of two different kinds of goods, A and B, to purchase. Assume that our prospective purchaser can assign an ordinal ranking to her consumption options, that her preferences are consistent and that, other things being equal, she always prefers more of a good to less. Each indifference curve represents the A–B combinations with which she is equally satisfied. Notice that these curves are not straight, but are convex from the origin, which demonstrates that A and B are not perfect substitutes. When the consumer has many of A, she would be willing to give up more than one of A to get one of B. The “marginal rate of substitution” between two goods measures the number of one kind of product that is necessary to remedy the loss to a consumer of a single other product. It declines because a consumer will give up increasingly less of A to get one more of B, and vice versa. The marginal rate of substitution measures the slope of the indifference curve.

As our consumer values more of both A and B, she prefers any indifference curve that is higher than another. Thus, she prefers I3 over I2 over I1. She would, of course, prefer indifference curves that are further from the origin than I3, but she faces what economists call a “constraint”. In this case, as in many cases in life, she can only afford to purchase so much. “B” represents an inviolable budgetary constraint.

The consumer acts rationally by maximising her utility, which she does by choosing the A:B product mix on the highest indifference curve that is still within her budget. This point is where her indifference curve farthest from the origin is tangential to her budget constraint, marked as “X*” (see Figure 1.1).

A person’s consumption choice depends on many factors. It depends most obviously on the individual’s utility function. That function, in turn, is not set in stone. Parenting, friends, education, religion, and culture all instil norms. The law, too, plays some role in shaping preferences and hence in informing the constitution of consumers’ utility functions. Law and economics analysis, however, generally assumes that consumers’ preferences are “exogenous” – in other words, it assumes that external factors, rather than the economic models under consideration, determine preferences. It also treats such preferences as “immutable”, which is to say unchangeable.

This feature of law and economics is simultaneously attractive and problematic. It is attractive because it takes a non-judgmental view on people’s desires, leaving each individual to decide for herself what she wants. It is problematic for much the same reason – it views as sacrosanct preferences that some people possess, but that most people would regard as distasteful or immoral. In appropriate settings, we shall discuss the possibility of relaxing these particular assumptions and explore how this might affect analysis.

Figure 1.1

2. The price effect

With the prior assumptions in place, the relative price of the goods in a person’s consumption bundle determines that individual’s consumption decision. What happens when the price of one good increases relative to that of another? Answering this question is important to the economic analysis of law, which views the legal system as a price-setting mechanism that induces people to substitute away from undesirable behaviour towards more-efficient conduct by increasing the cost of the former relative to the latter. The law performs this function through ex post liability, punitive sanctions, and injunctive decrees.

What is the effect of increasing the price of just one good in a consumption bundle? If a person considers two products, A and B, a rise in A’s price will have two consequences. First, there will be a “substitution effect”. Product A will now be worth less to the consumer at a given price and this will make interchangeable goods, in this example product B, more attractive. The marginal rate of substitution between goods A and B determines the magnitude of the substitution effect.

Second, a “wealth effect” will occur. The increase in the price of A will reduce our consumer’s wealth. Now less well off, an individual may view the goods available for her consumption differently. The larger the fraction of her wealth represented by the now-more-expensive good, the more significant the price effect will be. In tracing the impact of an elevated price on relative demand, economists draw a distinction between superior, normal, and inferior goods. Reduced wealth increases a person’s demand for inferior goods, reduces demand for normal goods proportionately with the reduction in wealth, and disproportionately lessens demand for superior goods. Superior and inferior goods probably include luxury sports cars and public transportation, respectively. The qualification is necessary because the nature of superiority, normality, and inferiority is not inherent in a product, but specific to the individual and to her specific tastes.

Applied to our example, if good A is superior relative to good B, the wealth effect will magnify the substitution effect toward good B. If good A is inferior relative to good B, however, then the wealth effect will have the opposite effect than the substitution effect. The net effect of the substitution and wealth effects is the price effect. This is the effect that typically concerns economists studying the legal system. If the law increases the cost of taking another’s property, breaching a contract, or filing a lawsuit, what will be the ultimate price effect (i.e. the change in behaviour)?

Could the wealth effect outweigh the substitution effect? If so, increasing the price of a product could magnify its demand. Applied to law and economics, this would mean that increasing the expected cost of committing a crime or acting negligently would increase the amount of crime or negligence – an odd res...