![]()

1

Adam Smith Declares an

Economic Revolution in 1776

Adam Smith was a radical and a revolutionary in his time—just as those of us who preach laissez faire are in our time.

—Milton Friedman (1978, 7)

The story of modern economics begins in 1776. Prior to this famous date, 6,000 years of recorded history had passed without a seminal work being published on the subject that dominated every waking hour of practically every human being: making a living.

For millennia, from Roman times through the Dark Ages and the Renaissance, humans struggled to survive by the sweat of their brow, often only eking out a bare existence. They were constantly guarding against premature death, disease, famine, war, and subsistence wages. Only a fortunate few—primarily rulers and aristocrats—lived leisurely lives, and even those were crude by modern standards. For the common man, little changed over the centuries. Real per capita wages were virtually the same, year after year, decade after decade. During this age, when the average life span was a mere forty years, the English writer Thomas Hobbes rightly called the life of man “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short” (1996 [1651], 84).

1776, a Prophetic Year

Then came 1776, when hope and rising expectations were extended to the common workingman for the first time. It was a period known as the Enlightenment, which the French called l’agedeslumieres. For the first time in history, workers looked forward to obtaining a basic minimum of food, shelter, and clothing. Even tea, previously a luxury, had become a common beverage.

The signing of America’s Declaration of Independence on July 4 was one of several significant events of 1776. Influenced by John Locke, Thomas Jefferson proclaimed “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” to be inalienable rights, thus establishing the legal framework for a struggling nation that would eventually become the greatest economic powerhouse on earth, and providing the constitutional foundation of liberty that was to be imitated around the world.

A Monumental Book Appears

Four months earlier, an equally monumental work had been published across the Atlantic in England. On March 9, 1776, the London printers William Strahan and Thomas Cadell released a 1,000-page, two-volume work entitled An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. It was a fat book with a long title destined to have gargantuan global impact. The author was Dr. Adam Smith, a quiet, absent-minded professor who taught “moral philosophy” at the University of Glasgow.

The Wealth of Nations was the intellectual shot heard around the world. Adam Smith, a leader in the Scottish Enlightenment, had put on paper a universal formula for prosperity and financial independence that would, over the course of the next century, revolutionize the way citizens and leaders thought about and practiced economics and trade. Its publication promised a new world—a world of abundant wealth, riches beyond the mere accumulation of gold and silver. Smith promised that new world to everyone—not just the rich and the rulers, but the common man, too. The Wealth of Nations offered a formula for emancipating the workingman from the drudgery of a Hobbesian world. In sum, The Wealth of Nations was a declaration of economic independence.

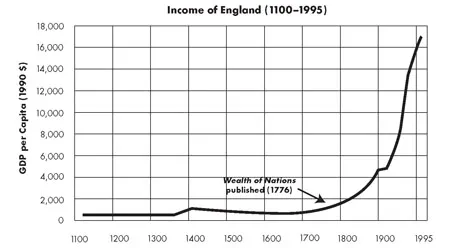

Courtesy of Larry Wimmer, Brigham Young University.

Figure 1.1 The Rise in Real per Capita Income, United Kingdom, 1100–1995

Certain dates are turning points in the history of mankind. The year 1776 is one of them. In that prophetic year, two vital freedoms were proclaimed—political liberty and free enterprise—and the two worked together to set in motion the Industrial Revolution. It was no accident that the modern economy began in earnest shortly after 1776 (see Figure 1.1).

The Enlightenment and the Rumblings of Economic Progress

The year 1776 was significant for other reasons as well. For example, it was the year the first volume of Edward Gibbon’s classic work, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88), appeared. Gibbon was a principal advocate of eighteenth-century Enlightenment, which embodied unbounded faith in science, reason, and economic individualism in place of religious fanaticism, superstition, and aristocratic power.

To Smith, 1776 was also an important year for personal reasons. His closest friend, David Hume, died. Hume, a writer and philosopher, was a great influence on Adam Smith (see “Pre-Adamites” in the appendix to this chapter). Like Smith, he was a leader of the Scottish Enlightenment and an advocate of commercial civilization and economic liberty.

For centuries, the average real wage and standard of living had stagnated, while almost a billion people struggled against the harsh realities of daily life. Suddenly, in the early 1800s, just a few years after the American Revolution and the publication of The Wealth of Nations, the Western world began to flourish as never before. The spinning jenny, power looms, and the steam engine were the first of many inventions that saved time and money for enterprising businessmen and the average citizen. The Industrial Revolution was beginning to unfold, real wages started climbing, and everyone’s standard of living, rich and poor, began rising to unforeseen heights. It was indeed the Enlightenment, the dawning of modern times, and people of all walks of life took notice.

Advocate for the Common Man

Just as George Washington was the father of a new nation, so Adam Smith was the father of a new science, the science of wealth. The great British economist Alfred Marshall called economics the study of “the ordinary business of life.” Appropriately, Adam Smith would have an ordinary name. He was named after the first man in the Bible, Adam, which means “out of many,” and his last name, Smith, signifies “one who works.” Smith is the most common surname in Great Britain.

The man with the pedestrian name wrote a book for the welfare of the average working man. In his magnum opus, he assured the reader that his model for economic success would result in “universal opulence which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people” (1965 [1776], 11).1

It was not a book for aristocrats and kings. In fact, Adam Smith had little regard for the men of vested interests and commercial power. His sympathies lay with the average citizens who had been abused and taken advantage of over the centuries. Now they would be liberated from sixteen-hour-a-day jobs, subsistence wages, and a forty-year life span.

Adam Smith Faces a Major Obstacle

After taking twelve long years to write his big book, Smith was convinced he had discovered the right kind of economics to create “universal opulence.” He called his model the “system of natural liberty.” Today economists call it the “classical model.” Smith’s model was inspired by Sir Isaac Newton, whose model of natural science Smith greatly admired as universal and harmonious.

Smith’s biggest hurdle would be convincing others to accept his system, especially legislators. His purpose in writing The Wealth of Nations was not simply to educate, but to persuade. Very little progress had been achieved over the centuries in England and Europe because of the entrenched system known as mercantilism. One of Adam Smith’s main objectives in writing The Wealth of Nations was to smash the conventional view of the economy, which allowed the mercantilists to control the commercial interests and political powers of the day, and to replace it with his view of the real source of wealth and economic growth, thus leading England and the rest of the world toward the “greatest improvement” of the common man’s lot.

The Appeal of Mercantilism

Following a long-standing tradition in the West, the mercantilists (the commercial politicos of the day) believed that the world’s economy was stagnant and its wealth fixed, so that one nation grew only at the expense of another. The economies of civilizations from ancient times through the Middle Ages were based on either slavery or several forms of serfdom. Under either system, wealth was largely acquired at the expense of others, or by the exploitation of man by man. As Bertrand de Jouvenel observes, “Wealth was therefore based on seizure and exploitation” (Jouvenel 1999, 100).

Consequently, European nations established government-authorized monopolies at home and supported colonialism abroad, sending agents and troops into poorer countries to seize gold and other precious commodities.

According to the established mercantilist system, wealth consisted entirely of money per se, which at the time meant gold and silver. The primary goal of every nation was always to aggressively accumulate gold and silver, and to use whatever means necessary to do so. “The great affair, we always find, is to get money,” Smith declared in The Wealth of Nations (398).

How to get more money? The growth of nations was predatory. Nations such as Spain and Portugal sent their emissaries to faraway lands to discover gold mines and to pile up as much of the precious metal as they could. No expedition or foreign war was too expensive when it came to their thirst for bullion. Other European countries, imitating the gold seekers, frequently imposed exchange controls, forbidding, under the threat of heavy penalties, the export of gold and silver.

Second, mercantilists sought a favorable balance of trade, which meant that gold and silver would constantly fill their coffers. How? “The encouragement of exportation, and the discouragement of importation, are the two great engines by which the mercantilist system proposes to enrich every country,” reported Smith (607). Smith carefully delineated the host of high tariffs, duties, quotas, and regulations that aimed at restraining trade. Ultimately, this system also restrained production and a higher standard of living. Such commercial interferences naturally led to conflict and war between nations.

Smith Denounces Trade Barriers

In a direct assault on the mercantile system, the Scottish philosopher denounced high tariffs and other restrictions on trade. Efforts to promote a favorable balance of trade were “absurd,” he declared (456). He talked of the “natural advantages” one country has over another in producing goods. “By means of glasses, hotbeds, and hotwalls, very good grapes can be raised in Scotland,” Smith said, but it would cost thirty times more to produce Scottish wine than to import wine from France. “Would it be a reasonable law to prohibit the importation of all foreign wines, merely to encourage the making of claret and burgundy in Scotland?” (425).

According to Smith, mercantilist policies merely imitate real prosperity, benefiting only the producers and the monopolists. Because it did not benefit the consumer, mercantilism was antigrowth and shortsighted. “In the mercantile system, the interest of the consumer is almost always constantly sacrificed to that of the producer,” he wrote (625).

Smith argued that trade barriers crippled the ability of countries to produce, and thus should be torn down. An expansion of trade between Britain and France, for example, would enable both nations to gain. “What is prudence in the conduct of every private family, can scarce be folly in that of a great kingdom,” declared Smith. “If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them” (424).

Real Source of Wealth Revealed

The accumulation of gold and silver might have filled the pockets of the rich and the powerful, but what would be the origin of wealth for the whole nation and the average citizen? That was Adam Smith’s paramount question. The Wealth of Nations was not just a tract on free trade, but a world view of prosperity.

The Scottish professor forcefully argued that the keys to the “wealth of nations” were production and exchange, not the artificial acquisition of gold and silver at the expense of other nations. He stated, “the wealth of a country consists, not of its gold and silver only, but in its lands, houses, and consumable goods of all different kinds” (418). Wealth should be measured according to how well people are lodged, clothed, and fed, not according to the number of bags of gold in the treasury. In 1763, he said, “the wealth of a state consists in the cheapness of provisions and all other necessaries and conveniences of life” (1982 [1763], 83).

Smith began his Wealth of Nations with a discussion of wealth. He asked, what could bring about the “greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour”? A favorable balance of trade? More gold and silver?

No, it was a superior management technique, “the division of labor.” In a well-known example, Smith described in detail the workings of a pin factory, where workers were assigned eighteen distinct operations in order to maximize the output of pins (1965 [1776], 3–5). This stages-of-production approach, where management works with labor to produce goods and fulfill consumer wants, forms the basis of a harmonious and growing economy. A few pages later, Smith used another example, the woolen coat: “the assistance and co-operation of many thousands” of laborers and various machinery from around the world were required to produce this basic product used by the “day-laborer”2 (11–12). Furthermore, expanding the market through worldwide trade would mean that specialization and division of labor could also expand. Through increased productivity, thrift, and hard work, the world’s output could increase. Hence, wealth was not a fixed quantity after all, and c...