eBook - ePub

An Institutionalist Guide to Economics and Public Policy

Marc R. Tool

This is a test

Share book

- 350 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Institutionalist Guide to Economics and Public Policy

Marc R. Tool

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This narrative recounts the 18th and 19th century "shipping out" of Pacific islanders aboard European and American vessels, a kind of "counter-exploring", that echoed the ancient voyages of settlement of their island ancestors.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is An Institutionalist Guide to Economics and Public Policy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access An Institutionalist Guide to Economics and Public Policy by Marc R. Tool in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A Geobased National Agricultural Policy For Rural Community Enhancement, Environmental Vitality, and Income Stabilization

F. Gregory Hayden

We all have a great stake in agricultural policy because we all consume food, but also because of other equally important considerations such as the connections between soil and civilization, between the rural exodous and urban problems, and between farming and urban water supplies. Edward Hyams emphasized the civilization connection in his book Soil and Civilization.1 F. Ray Marshall has stated that we will never solve the urban problem until we solve the rural problem.2 Larry D. Swanson demonstrates the water linkage in another article in this issue.3 Although we are all affected by agricultural policy, Secretary of Agriculture John Block emphasized interests of large agribusiness during the week of July 10, 1983, when he brought together a group to map the future of agricultural policy in the United States.4 Noticeably absent were urban interests, environmentalists, consumer groups, nutritionists, diplomats, religious groups against hunger, rural community associations, small farm advocates, and directors of the states’ agricultural departments.

In considering consequences, there is probably nothing that more exemplifies the Veblenian dichotomy, which distinguishes between substantive economics and pecuniary valuation, than the policies applied to agriculture and rural communities. Substantive economic policies are concerned with matters such as nutritional adequacy, energy use, environmental damage, adequate incomes, gated irrigation pipes, water aquifers, protein ratios, technological assessment, and so forth. The substantive concerns are conveniently ignored by those who judge everything by the volume of pecuniary sales. Deference to the latter criterion has misled some to emphasize policies such as fence-row planting and export maximization. As Robert Reich has stated, the soil and environment (substantive issues) cannot sustain such policies.5 Neither can rural communities. During the alleged good years in agriculture in the 1970s, soil erosion was high, efficient farmers were still going broke at a rapid rate, and people were being dumped out of the countryside into the overburdened cities.

When policymakers narrow their view to pecuniary or gross output concerns, they find U.S. agriculture to be a very efficient system. As was documented elsewhere, it is an international agribusiness that

destroys cities by overloading them with displaced persons; destroys rural communities and their social services because there are not enough people to support them; destroys topsoil and water supplies; poisons ground and surface water supplies with chemicals, pesticides, and fertilizers; augments desertification; destroys soil humus and porosity, which means less water retention, which means that compacted soil needs larger tractors which further compact soil; leaches nutrients from and adds salts to the soil through irrigation; uses more energy than it produces; causes worker sterility in the fertilizer factories; creates health problems for farmers who apply the toxic fertilizer, pesticides, and herbicides; uses fertilizers which prevent plants from absorbing nutrients necessary for human health; fills the food chain with carcinogenic pesticides, herbicide growth hormones, and antibiotics; creates an expensive and unnecessary transportation system; diverts millions of acres each year in Third World countries to nonfood production; processes the nutrients out of what food is produced with the profits being greater, the greater the amount of processing; and fills the processed product with carcinogenic preservatives, refined sugars, salt, and artificial colors.6

The rural depopulation in the United States and consequent urban concentration

have been accomplished by paying the majority of government subsidies to rich farmers; paying more subsidies the more acreage left idle; paying nothing to labor idled with the land; paying the highest price subsidies to those with the greatest production; subsidizing capital equipment but not labor; providing large research and irrigation projects to complement big producers’ technology; allowing subsidy programs to be capitalized into the price of farmland so that only the rich can afford the land; providing government crop insurance and loan guarantees to remove the risk for absentee owners; and providing special tax loopholes to protect large incomes from taxation, such that 80 percent of farm tax “losses” accrue to those in the 10 largest metropolitan areas.As people are driven from the farms, rural towns have decreasing business sales, employment, income, and property valuations, and taxes become inadequate to support public services. In addition, national and state government has failed to provide adequate public services to rural areas. The final result has been pervasive societal disintegration and mass migration to urban areas in an attempt by rural people to avoid personal decay.7

It is amazing how badly U.S. agricultural policy has guided the performance of the world’s best educated and most technically competent farmers and the world’s best land and resources.

The Agribusiness Technostructure As A System

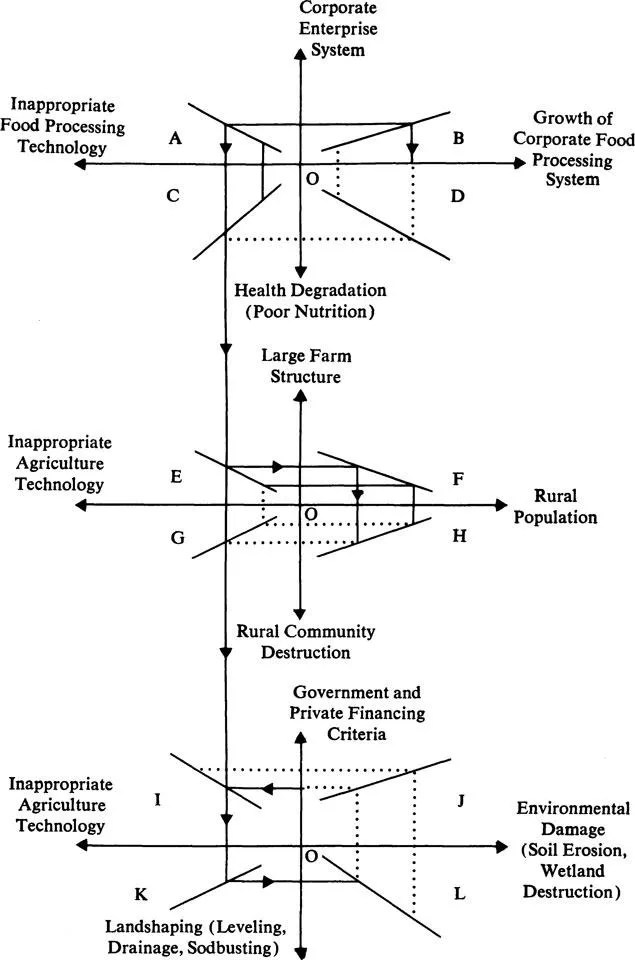

Figure 1 is an attempt to disaggregate the system into a set of binary relationships in order to indicate the kind of policy considerations that need to be addressed. The relationships are indicated by the positive and negative slopes of the curves in each quadrant. All axes of all quadrants are positive. The connection among the quadrants can be traced by the use of the line connecting them. Dashed lines are used when a curve is derived from two adjoining curves. The axis at the top of Figure 1 indicates the growth of the corporate enterprise system explained by John Kenneth Galbraith, Jim Hightower, and others, with regard to the world of agriculture and food processing. As indicated in quadrant A, the corporate technostructure has promoted inappropriate technology in both agriculture and food processing. Quadrant B indicates that food processing has also been incorporated into the corporate enterprise system and is guided by the same goals and incentives. Therefore it is not surprising to find, as indicated in quadrant D, that the growth of the corporate food processing system has led, as stated above, to processing the nutrients from food and replacing them with sugars, fats, and salts, thereby contributing to health problems. As explained by Paul Dale Bush and Louis Junker, the “ceremonial encapsulation” of the knowledge and technology by the corporate enterprise system leads ultimately, as indicated in quadrants C and D, to a situation where technology becomes significantly health threatening instead of life enhancing.8

When we move down to quadrants E, F, G, and H, we find that similar encapsulation has also created a farm structure and agricultural technology that has destroyed rural communities. Scientific work has been completed on this linkage by Walter Goldschmidt, Larry D. Swanson, Steve E. Sonka, Earl O. Heady, and others, for different time periods in different locations.9 The large equipment and chemicals that replaced labor on the farm have been delivered to and promoted on the farms by the corporate producers and by many professionals at the land grant universities. From a substantive economic point of view, this equipment is inefficient in total system cost, energy use, and employment enhancement. To the individual farmer, it is expensive in both capital cost and operating cost.

Figure 1. The Agribusiness Technostructure as a System of Binary Relationships.

The only way to justify acquisition of large equipment (quadrant E) is by accumulating more land, sufficient to use the capacity of the equipment. As everyone pushes for larger farms the price of land is bid up, thereby increasing the failure rate as credit requirements and interest costs increase. The large high-debt farmers go broke at a more rapid rate, and the large farms accumulated are then bought by still larger, established farmers and by outside interests such as Prudential Insurance Company, Time, Texaco, and others.10 They do not revert to efficient-sized farms because smaller or younger farmers cannot acquire the funds to compete in the land acquisition race. As larger, more politically powerful groups enter into farming, more and more government funds and research are made available to prop up the large farms. The consequence is a farm structure made up of fewer farmers, with more of them continuing to leave the countryside each year. As displayed in quadrant F, as the large farm structure evolves, there is less need for teachers, retailers, ministers, and so forth in the rural towns, so population in the rural community decreases more than just the amount of the migrating farm family. Thus as indicated in H, the rural population decline destroys the rural community. This leaves us with the result, indicated in quadrant G, that our agricultural technology and knowledge base destroy rather than enhance the viability of our communities. The popular view, reinforced in university and high school macroeconomics, is that investment is always good. That must be questioned. What needs to be understood is that investment can be destructive if it is in inappropriate technology.

The bottom set of quadrants (I, J, K, and L) in Figure 1 indicate that connections among financing, technology, and environmental damages. This connection is not separate from the corporate and farm structures issues, but is rather a special elaboration of the same system. Soil, water, fish, and wildlife are being systematically destroyed in this nation by the agricultural sector. For example, soil erosion in excess of 5 tons per acre per year is occurring on 25 percent of the 413 million acres of land now devoted to crop production. It is in excess of 15 tons per acre per year on 25 million acres of that cropland. In some places it is greater than 300 tons per acre per year.11 We cannot maintain a civilization at this rate of destruction. As displayed in quadrant I, the financing criteria used to determine how the agriculture investment funds are to be used have encouraged the destructive use of technology. Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service (ASCS) conservation funds have been used in conjunction with private credit to drain potholes and wetlands across the nation, thereby destroying the nesting and staging areas of ducks, geese, cranes, and so forth. Farmers Home Administration funds have been used to break the sod in areas highly susceptible to soil erosion.12 The land-shaping techniques indicated in quadrant L have led to environmental damage; the resulting relationship between public and private financing criteria and environmental damage is indicated in quadrant J.

The important contribution of Figure 1, lest we get lost in the binary trees, is to demonstrate that the current situation is a result of government and corporate policies, and not the result of any natural or deterministic force rooted in efficiency compulsions or technological givens. The policy base has been ideological. Therefore these policies are discretionary; they can be changed.