![]()

1 Preliminaries

By way of setting the stage, this opening chapter introduces some of the most important metaphysical issues concerning time and space. Although many of the questions that can be asked about time can also be asked about space, and vice versa, time raises distinctive issues all of its own, and I will be devoting special attention to these. Some of the distinctive issues concerning space are discussed in Chapter 9.

1.1 Ontology: the existence of space and time

Do space and time exist? This is an obvious question, and one that is frequently addressed, but it can mean different things. Since philosophers raise the question of whether the physical world as a whole exists, it is not surprising that they ask the same question of space and time. However, the question "Do space and time exist?" is usually not asked in the context of a general scepticism. Those who pose this question generally assume that the world is roughly as it seems to be: objects are spatially extended (a planet is bigger than an ant), objects exist at different places and things happen at different times. So what is usually meant by the question is this: "Are space and time entities in their own right, over and above things such as stars, planets, atoms and people?"

The answer is not obvious, and for an obvious reason: both space and time are invisible. We can see things change and move, and by observing changes we can tell that time has elapsed, but of time itself we never catch a glimpse. The same applies to space. We can see that things are spatially extended, and we can observe that two objects are separated by a certain distance, but that is all. Indeed, the very idea that space exists can seem nonsensical.

When two objects are separated by an expanse of empty space there appears to be strictly nothing between them (ignoring what appears behind them). If space is just nothing, how can it possibly be something? But, of course, whether empty space really is just "nothing" is precisely what is at issue, and invisibility is an unreliable guide to non-existence. Science posits lots of invisible entities (neutrinos, force-fields) that many believe to exist; perhaps space and time fall into the same category. Clearly, the fact that space and time are not directly observable does complicate matters. If we are to believe that space and time exist as entities in their own right, we need to be given compelling reasons; the situation is different with observable things such as rabbits and houses.

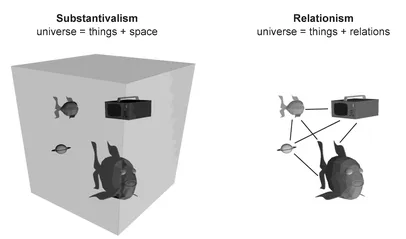

Figure 1.1 The substantival and relational conceptions of space. A pair of space-fish go about their business. The shaded block on the left represents space (or at least a small portion of it) as construed by the substantivalist. On this view, the "void" between material objects is far from empty: it is filled by an extended (if invisible) entity. Relationists reject this entity – and so regard "empty space" to be just that – but they also maintain that material objects (likewise their constituent parts) are connected to one another: by "spatial relations". These relations are usually taken to be basic ingredients of the universe, which connect things directly, i.e. without passing through the intervening void (in this respect the picture on the right is misleading).

There are two opposed views on this ontological issue that have a variety of names, but that for now we can call "substantivalism" and "relationism". Substantivalists maintain that a complete inventory of the universe would mention every material particle and also mention two additional entities: space and time. The relationist denies the existence of these entities. For them the world consists of material objects, spatiotemporal relations and nothing else. Figure 1.1 illustrates the difference between these two competing views; to simplify the picture only a small volume of space is shown, and time is omitted altogether.

It is important to note that in denying the existence of space and time as objects in their own right relationists are not claiming that statements about where things are located or when they happen are false; they readily admit that there are spatial and temporal relations or distances between objects and events. What they claim is that recognizing the existence of spatial and temporal relations between things doesn't require us to subscribe to the view that space and time are entities in their own right. The relationist is, of course, required to give a convincing account of what these "relations" are, and how they manage to perform the roles required of them.

The substantivalist is sometimes said to regard space and time as being akin to containers, within which everything else exists and occurs. In one sense this characterization of substantivalism is accurate, but in another it is misleading. An ordinary container, such as a box, consists of a material shell and nothing else. If all the air within an otherwise empty box is removed, the walls of the box are all that remain. Contemporary substantivalists do not think of space and time in this way; they think of them as continuous and pervasive mediums that extend everywhere and "everywhen". The air can be removed from a box, but the space cannot, and if space is substantival, a so-called empty box remains completely filled with substantival space, as does the so-called "empty space" between the stars and galaxies. Roughly speaking, a substantivalist holds that space and time "contain" objects in the way that an ocean contains the solid things that float within it.

It is plain that the verdict we reach on the ontological question concerning space and time has momentous implications for what the universe contains. If the substantivalist is correct, space and time are the biggest things there are. The relationist view is much more economical: the vast pervasive mediums posited by the substantivalist simply do not exist.

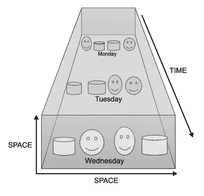

We will start to explore this issue in Chapter 9, and it will remain centre stage for much of the remainder of the book. Although the initial focus will be on space, the ontological status of time will not be ignored, even though it will not receive separate treatment (in Chapters 2-8, where time occupies centre stage, the substantivalism–relationism controversy will not feature at all). Since any spatial point also has a temporal location, it is more properly viewed as a point in space and time, i.e. as a "spacetime point". The substantivalist takes the totality of these spacetime points to be a real entity: "spacetime". Figure 1.2 shows a small portion of a substantival spacetime – the translucent block – over a period of three days (one spatial dimension is suppressed). Clearly, if this conception is correct, time is just as real as space.

Figure 1.2 Spatio temporal ("spacetime") substantivalism. Material objects are distributed through an extended medium composed of spacetime points. Since one spatial dimension has been suppressed, each two-dimensional slice of the block represents a three-dimensional volume of space.

1.2 Questions of structure

Irrespective of how the debate between substantivalists and relationists is resolved, there are questions to be addressed concerning what can loosely be called the "structural" characteristics of space and time. Whereas substantivalists take these questions to be about actual entities, relationists take them to be about the ways material things are related in spatial and temporal ways. To get some impression of the flavour of these structural questions consider the following claims:

- Space is infinite in size, three-dimensional, Euclidean (so travellers moving along parallel trajectories will never meet), isotropic (there is no privileged spatial direction) and continuous (infinitely divisible).

- Time is infinite, one-dimensional, linear, anisotropic (there is a privileged temporal direction) and continuous.

- There is just one space, and one time.

- Time and space are absolute, in that they are unaffected by the presence or absence (or distribution) of material things.

Some readers may find this characterization quite plausible. Those with some knowledge of ancient and medieval cosmologies will realize that it is similar to one defended by the ancient atomists but soon rejected in favour of the Aristotelian system (which posited, among other things, a finite, non-homogeneous and anisotropic space), and which returned to favour only in the 1500s. Those with some scientific (or science fiction) background will realize that this essentially Newtonian conception was overturned by Einstein's theories of special and general relativity in the early years of the twentieth century. More recently, some quantum theorists have argued that time is branching rather than linear, while others maintain that time does not exist; relativistic cosmologists have argued that there may be a multiplicity of spacetimes (or "baby universes") sprouting from the other end of black holes, and superstring theorists argue for the astonishing view that there are nine (or more) spatial dimensions.

Fascinating as many of these recent theories are, this is not the place for a thorough discussion of them, although their implications are such that they can scarcely be ignored either. Where space is concerned, my main focus will be on the substantivalist–relationist controversy, and I will only be looking at the structural issues that are relevant to it. Since it turns out that a good many structural issues are relevant to it, we shall have occasion to enter into at least the shallows of these perplexing waters.

1.3 Physics and metaphysics

Are there any facts about space and time that are necessary (hold in all possible worlds), and that can be established by a priori reasoning? Or are the answers to all of the interesting questions about space and time contingent and a posteriori, and hence to be answered only by the relevant sub-branches of science – physics and cosmology? If we answer "yes" to the latter question, the philosophy of space and time reduces to a branch of the philosophy of science and we must confine ourselves to examining the content of contemporary scientific theories, in particular relativity and quantum theory.

This has something to be said for it for, as we have just seen, scientists have made claims about space and time that provide answers to many of the questions philosophers have struggled with; many (if not all) of the relevant theories are well confirmed and so cannot be ignored. It would also be fair to say that science and mathematics have provided us with new ways of thinking about space and time, ways that philosophers may never have stumbled across if left to their own devices. The following simple but influential argument dates back to ancient Greek times:

The idea that space is finite can be shown to be absurd. Suppose that space were finite. If you travelled to the outermost boundary of space and tried to continue on, what would happen? Surely you could move through this supposed barrier. What could stop you, since by hypothesis there is nothing on the other side? In which case, the supposed limit isn't really the end of space. Since this reasoning applies to any supposed edge of space, space must be infinite.

There are replies the metaphysician can make. For example:

By definition, to move is to change your place in space. Accordingly, it makes no sense at all to suppose you could move beyond the edge of space, since by hypothesis there are no places beyond this limit for you to occupy. Consequently, the assumption that space is finite does not result in an absurdity.

This may seem reasonable enough, but there are further moves and countermoves available to the metaphysician. Does the reply tacitly assume a substantivalist view of space? A relationist would reject the very idea that motion consists of moving on to pre-existing spatial locations; if motion consists instead of an object changing its spatial relations to other objects, what is to prevent an object from moving ever further from other objects? And so it proceeds. But as we shall see in Chapter 13, the assumptions underlying this debate were completely transformed in the nineteenth century by the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries and the possibility that a space could be curved. If our space were positively curved – a three-dimensional counterpart of the surface of a sphere – someone could set off on a journey, always travel in a straight line (never deviating to the right or left), and still end up just where they started. Space can thus be finite without possessing any limits, edges or obstacles to movement. This is just one example of how philosophical discussions of space and time have been influenced if not rendered redundant by developments in physics and mathematics; there are others.

However, while the science is important, there are several reasons why it would be a mistake to suppose that only science matters, and that considerations of a philosophical sort are dispensable. First of all, physics and metaphysics are to some degree interdependent. When evaluating a theory, when inventing a theory, scientists are themselves influenced, in part, by metaphysical considerations: by what it makes sense to say the world is like. Moreover, the metaphysical implications of a scientific theory – i.e. what implications the mathematical formalism has for how the world is – are often unclear. This is especially true of relativity and quantum theory. Hence there is a need for metaphysical inquiry, even if this inquiry does not take place independently of scientific theorizing.

But metaphysics also has its own distinctive domains and methods of inquiry. While it may well be that to discover the answers to some questions about the space and time in our world we will have to listen to the physicist, there are other questions for which this is not so. Some of these questions are about topics that lie altogether outside the domain of physics: for example the role space plays in our ordinary modes of thought; the way time manifests itself in human consciousness; our different attitudes to the past, present and future, and their rationality...