bh I requested that Charles sing "Precious Lord" because the conditions that led Thomas Dorsey to write this song always make me think about gender issues, issues of Black masculinity. Mr. Dorsey wrote this song after his wife died in childbirth. That experience caused him to have a crisis of faith. He did not think he would be able to go on living without her. That sense of unbearable crisis truly expresses the contemporary dilemma of faith. Mr. Dorsey talked about the way he tried to cope with this "crisis of faith." He prayed and prayed for a healing and received the words to this song. This song has helped so many folk when they are feeling low, feeling as if they can't go on. It was my grandmother's favorite song. I remember how we sang it at her funeral. She died when she was almost ninety. And I am moved now as I was then by the knowledge that we can take our pain, work with it, recycle it, and transform it so that it becomes a source of power.

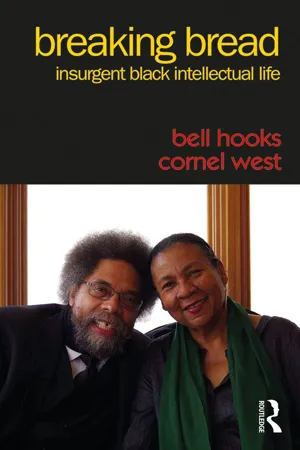

Let me introduce to you my "brother," my comrade Cornel West.

CW First I need to just acknowledge the fact that we as Black people have come together to reflect on our past, present, and future. That, in and of itself, is a sign of hope. I'd like to thank the Yale African American Cultural Center for bringing us together, bell and I thought it would be best to present in dialogical form a series of reflections on the crisis of Black males and females. There is a state of siege raging now in Black communities across this nation linked not only to drug addiction but also to consolidation of corporate power as we know it, and redistribution of wealth from the bottom to the top, coupled with the ways with which a culture and society centered on the market, preoccupied with consumption, erode structures of feeling, community, tradition. Reclaiming our heritage and sense of history are prerequisites to any serious talk about Black freedom and Black liberation in the 21st century. We want to try to create that kind of community here today, a community that we hope will be a place to promote understanding. Critical understanding is a prerequisite for any serious talk about coming together, sharing, participating, creating bonds of solidarity so that Black people and other progressive people can continue to hold up the blood-stained banners that were raised when that song was sung in the civil rights movement. It was one of Dr. Martin Luther King's favorite songs, reaffirming his own struggle and that of many others who have tried to link some sense of faith, religious faith, political faith, to the struggle for freedom. We thought it would be best to have a dialogue to put forth analysis and provide a sense of what form a praxis would take. That praxis will be necessary for us to talk seriously about Black power, Black liberation in the 21st century.

bh Let us say a little bit about ourselves. Both Cornel and I come to you as individuals who believe in God. That belief informs our message.

CW One of the reasons we believe in God is due to the long tradition of religious faith in the Black community. I think, that as a people who have had to deal with the absurdity of being Black in America, for many of us it is a question of God and sanity, or God and suicide. And, if you are serious about Black struggle, you know that in many instances you will be stepping out on nothing, hoping to land on something. That is the history of Black folks in the past and present, and it continually concerns those of us who are willing to speak out with boldness and a sense of the importance of history and struggle. You speak, knowing that you won't be able to do that for too long because America is such a violent culture. Given those conditions, you have to ask yourself what links to a tradition will sustain you, given the absurdity and insanity we are bombarded with daily. And so the belief in God itself is not to be understood in a noncontextual manner. It is understood in relation to a particular context, to specific circumstances.

bh We also come to you as two progressive Black people on the Left.

CW Very much so.

bh I will read a few paragraphs to provide a critical framework for our discussion of Black power, just in case some of you may not know what Black power means. We are gathered to speak with one another about Black power in the 21st century. In James Boggs's essay, "Black Power: A Scientific Concept Whose Time Has Come," first published in 1968, he called attention to the radical political significance of the Black power movement, asserting: "Today the concept of Black power expresses the revolutionary social force which must not only struggle against the capitalist but against the workers and all who benefit by and support the system which has oppressed us." We speak of Black power in this very different context to remember, reclaim, re-vision, and renew. We remember first that the historical struggle for Black liberation was forged by Black women and men who were concerned about the collective welfare of Black people. Renewing our commitment to this collective struggle should provide a grounding for new direction in contemporary political practice. We speak today of political partnership between Black men and women. The late James Baldwin wrote in his autobiographical preface to Notes of a Native Son: "I think that the past is all that makes the present coherent and further that the past will remain horrible for as long as we refuse to accept it honestly." Accepting the challenge of this prophetic statement as we look at our contemporary past as Black people, the space between the sixties and the nineties, we see a weakening of political solidarity between Black men and women. It is crucial for the future of Black liberation struggle that we remain ever mindful that ours is a shared struggle, that we are each other's fate.

CW I think we can even begin by talking about the kind of existentialist chaos that exists in our own lives and our inability to overcome the sense of alienation and frustration we experience when we try to create bonds of intimacy and solidarity with one another. Now part of this frustration is to be understood again in relation to structures and institutions. In the way in which our culture of consumption has promoted an addiction to stimulation— one that puts a premium on packaged and commodified stimulation. The market does this in order to convince us that our consumption keeps oiling the economy in order for it to reproduce itself. But the effect of this addiction to stimulation is an undermining, a waning of our ability for qualitatively rich relationships. It's no accident that crack is the postmodern drug, that it is the highest form of addiction known to humankind, that it provides a feeling ten times more pleasurable than orgasm.

bh Addiction is not about relatedness, about relationships. So it comes as no surprise that, as addiction becomes more pervasive in Black life, it undermines our capacity to experience community. Just recently, I was telling someone that I would like to buy a little house next door to my parent's house. This house used to be Mr. Johnson's house but he recently passed away. And they could not understand why I would want to live near my parents. My explanation that my parents were aging did not satisfy. Their inability to understand or appreciate the value of sharing family life inter-generationally was a sign to me of the crisis facing our communities. It's as though as Black people we have lost our understanding of the importance of mutual interdependency, of communal living. That we no longer recognize as valuable the notion that we collectively shape the terms of our survival is a sign of crisis.

CW And when there is crisis in those communities and institutions that have played a fundamental role in transmitting to younger generations our values and sensibility, our ways of life and our ways of struggle, we find ourselves distanced, not simply from our predecessors but from the critical project of Black liberation. And so, more and more, we seem to have young Black people who are very difficult to understand, because it seems as though they live in two very different worlds. We don't really understand their music. Black adults may not be listening to NWA (Niggers With Attitude) straight out of Compton, California. They may not understand why they are doing what Stetsasonic is doing, what Public Enemy is all about, because most young Black people have been fundamentally shaped by the brutal side of American society. Their sense of reality is shaped on the one hand by a sense of coldness and callousness, and on the other hand by a sense of passion for justice, contradictory impulses which surface simultaneously. Mothers may find it difficult to understand their children. Grandparents may find it difficult to understand us—and it's this slow breakage that has to be restored.

bh That sense of breakage, or rupture, is often tragically expressed in gender relations. When I told folks that Cornel West and I were talking about partnership between Black women and men, they thought I meant romantic relationships. I replied that it was important for us to examine the multi-relationships between Black women and men, how we deal with fathers, with brothers, with sons. We are talking about all our relationships across gender because it is not just the heterosexual love relationships between Black women and men that are in trouble. Many of us can't communicate with parents, siblings, etc. I've talked with many of you and asked, "What is it you feel should be addressed?" And many of you responded that you wanted us to talk about Black men and how they need to "get it together."

Let's talk about why we see the struggle to assert agency— that is, the ability to act in one's best interest—as a male thing. I mean, Black men are not the only ones among us who need to "get it together." And if Black men collectively refuse to educate themselves for critical consciousness, to acquire the means to be self-determined, should our communities suffer, or should we not recognize that both Black women and men must struggle for self-actualization, must learn to "get it together"? Since the culture we live in continues to equate Blackness with maleness, Black awareness of the extent to which our survival depends on mutual partnership between Black women and men is undermined. In renewed Black liberation struggle, we recognize the position of Black men and women, the tremendous role Black women played in every freedom struggle.

Certainly, Septima Clark's book Ready from Within is necessary reading for those of us who want to understand the historical development of sexual politics in Black liberation struggle. Clark describes her father's insistence that she not fully engage herself in civil rights struggle because of her gender. Later, she found the source of her defiance in religion. It was the belief in spiritual community, that no difference must be made between the role of women and that of men, that enabled her to be "ready within." To Septima Clark, the call to participate in Black liberation struggle was a call from God. Remembering and recovering the stories of how Black women learned to assert historical agency in the struggle for self-determination in the context of community and collectivity is important for those of us who struggle to promote Black liberation, a movement that has at its core a commitment to free our communities of sexist domination, exploitation, and oppression. We need to develop a political terminology that will enable Black folks to talk deeply about what we mean when we urge Black women and men to "get it together."

CW I think again that we have to keep in mind the larger context of American society, which has historically expressed contempt for Black men and Black women. The very notion that Black people are human beings is a new notion in Western Civilization and is still not widely accepted in practice. And one of the consequences of this pernicious idea is that it is very difficult for Black men and women to remain attuned to each other's humanity, so when bell talks about Black women's agency and some of the problems Black men have when asked to acknowledge Black women's humanity, it must be remembered that this refusal to acknowledge one another's humanity is a reflection of the way we are seen and treated in the larger society. And it's certainly not true that White folks have a monopoly on human relationships. When we talk about a crisis in Western Civilization, Black people are a part of that civilization, even though we have been beneath it, our backs serving as a foundation for the building of that civilization, and we have to understand how it affects us so that we may remain attuned to each other's humanity, so that the partnership that bell talks about can take on real substance and content. I think partnerships between Black men and Black women can be made when we learn how to be supportive and think in terms of critical affirmation.

bh Certainly, Black people have not talked enough about the importance of constructing patterns of interaction that strengthen our capacity to be affirming.

CW We need to affirm one another, support one another, help, enable, equip, and empower one another to deal with the present crisis, but it can't be uncritical, because if it's uncritical, then we are again refusing to acknowledge other people's humanity. If we are serious about acknowledging and affirming other people's humanity, then we are committed to trusting and believing that they are forever in process. Growth, development, maturation happens in stages. People grow, develop, and mature along the lines in which they are taught. Disenabling critique and contemptuous feedback hinders.

bh We need to examine the function of critique in traditional Black communities. Often it does not serve as a constructive force. Like we have that popular slang word "dissin'," and we know that "dissin'" refers to a kind of disenabling contempt—when we "read" each other in ways that are so painful, so cruel, that the person can't get up from where you have knocked them down. Other destructive forces in our lives are envy and jealousy. These undermine our efforts to work for a collective good. Let me give a minor example. When I came in this morning I saw Cornel's latest book on the table. I immediately wondered why my book was not there and caught myself worrying about whether he was receiving some gesture of respect or recognition denied me. When he heard me say, "Where's my book?" he pointed to another table.

Often when people are suffering a legacy of deprivation, there is a sense that there are never enough goodies to go around, so that we must viciously compete with one another. Again this spirit of competition creates conflict and divisiveness. In a larger social context, competition between Black women and men has surfaced around the issue of whether Black female writers are receiving more attention than Black male writers. Rarely does anyone point to the reality that only a small minority of Black women writers are receiving public accolades. Yet the myth that Black women who succeed are taking something away from Black men continues to permeate Black psyches and inform how we as Black women and men respond to one another. Since capitalism is rooted in unequal distribution of resources, it is not surprising that we as Black women and men find ourselves in situations of competition and conflict.

CW I think part of the problem is deep down in our psyche we recognize that we live in such a conservative society, a society disproportionately shaped by business elites, a society in which corporate power influences are assuring that a certain group of people do get up higher.

bh Right, including some of you in this room.

CW And this is true not only between male and female relations but also Black and Brown relations, and Black and Red, and Black and Asian relations. We are struggling over crumbs because we know that the bigger part has been received by elites in corporate America. One half of one percent of America owns twenty-two percent of the wealth, one percent owns thirty-two percent, and the bottom forty-five percent of the population has two percent of the wealth. So, you end up with this kind of crabs-in-the-barrel mentality. When you see someone moving up, you immediately think they'll get a bigger cut in big-loaf corporate America, and you think that's something real because we're still shaped by the corporate ideology of the larger context.

bh Here at Yale, many of us are getting a slice of that mini-loaf and yet are despairing. It was discouraging when I came here to teach and found in many Black people a quality of despair which is not unlike what we know is felt in "crack neighborhoods." I wanted to understand the connection between underclass Black despair and that of Black people here who have immediate and/or potential access to so much material privilege. This despair mirrors the spiritual crisis that is happening in our culture as a whole. Nihilism is everywhere. Some of this despair is rooted in a deep sense of loss. Many Black folks who have made it or are making it undergo an identity crisis. This is especially true for individual Black people working to assimilate into the "mainstream." Suddenly, they may feel panicked, alarmed by the knowledge that they do not understand their history, that life is without purpose and meaning. These feelings of alienation and estrangement create suffering. The suffering many Black people experience today is linked to the suffering of the past, to "historical memory." Attempts by Black people to understand that suffering, to come to terms with it, are the conditions which enable a work like Toni Morrison's Beloved to receive so much attention. To look back, not just to describe slavery but to try and reconstruct a psycho-social history of its impact has only recently been fully understood as a necessary stage in the process of collective Black self-recovery.

CW The spiritual crisis that has happened, especially among the well-to-do Blacks, has taken the form of the quest for therapeutic release. So that you can get very thin, flat, and one-dimensional forms of spirituality that are simply an attempt to sustain the well-to-do Black folks as they engage in their consumerism and privatism. The kind of spirituality we're talking about is not the kind that serves as an opium to help you justify and rationalize your own cynicism vis-à-vis the disadvantaged folk in our community. We could talk about churches and their present role in the crisis of America, religious faith as the American way of life, the gospel of health and wealth, helping the bruised psyches of the Black middle class make it through America. That's not the form of spirituality that we're talking about. We're talking about something deeper— you used to call it conversion—so that notions of service and risk and sacrifice once again become fundamental. It's very important, for example, that those of you who remember the days in which Black colleges were hegemonic among the Black elite remember them critically but also acknowledge that there was something positive going on there. What was going on was that you were told every Sunday, in chapel, that you had to give service to the race. Now it may have been a petty bourgeois form, but it created a moment of accountability, and with the erosion of the service ethic the very possibility of putting the needs of others alongside of one's own diminishes. In this syndrome, me-ness, selfishness, and egocentricity become more and more prominent, creating a spiritual crisis where you need more psychic opium to get you over.

bh We have experienced such a change in that communal ethic of service that was so necessary for survival in traditional Black communities. That ethic of service has been altered by shifting class relations. And even those Black folks who have little or no class mobility may buy into a bourgeois class sensibility; TV shows like Dallas and Dynasty teach ruling class ways of thinking and being to underclass poor people. A certain kind of bourgeois individualism of the mind prevails. It does not correspond to actual class reality or circumstances of deprivation. We need to remember the many economic structures and class politics that have led to a shift of priorities for "privileged" Blacks. Many privileged Black folks obsessed with living out a bourgeois dream of liberal individualistic success no longer feel as though they have any accountability in relation to the Black poor and underclass.

CW We're not talking about the narrow sense of guilt privileged Black people can feel, because guilt usually paralyzes action. What we're talking about is how one uses one's time and energy. We're talking about the ways in which the Black middle class, which ...